Update (May 15, 2019): This post was linked and its author quoted as a source in this Fast Company article on the same subject.

Where’s my webcam’s off switch?

Have you ever noticed that your webcam doesn’t have an “off” switch? I looked on Amazon, and I couldn’t find any webcams for sale that had a simple on/off switch. When I thought I found one, it turned out just to have a light that turns on when the camera is in use, and off when not—not a physical switch you can press or slide.

The “clever” solution is supposed to be webcam covers (something Mark Zuckerberg had a hand in popularizing); you can even get a webcam (or a laptop) with such a cover built in. How convenient! I’ve used tape, which works fine.

But a cover doesn’t cover up the microphone, which could be turned on without your knowledge. Oh, you think that’s impossible? Here are some handy instructions. Or maybe you’ll say you’re not paranoid—it’s not a serious problem? Don’t be so naive, said the FBI seven years ago (they’re worried about predators stalking children), and the Atlantic, and USA Today more recently. The issue isn’t going away. With hacking skills growing more common, the problem has surely grown, if anything, more dire.

Another “clever” solution is to use a software off switch, like this (for Windows). But it simply turns your webcam’s driver on and off. Of course, it’s not too hard for a sufficiently skilled hacker to turn your driver back on and start recording you without your knowledge.

For USB devices, you can use a USB off switch like this, which seems like a good idea; but it doesn’t solve the problem for devices with built-in cameras and microphones like laptops and smart phones.

The humble “off” switch is now high technology. It is a significant selling point for the single device that I could find that comes equipped with one.

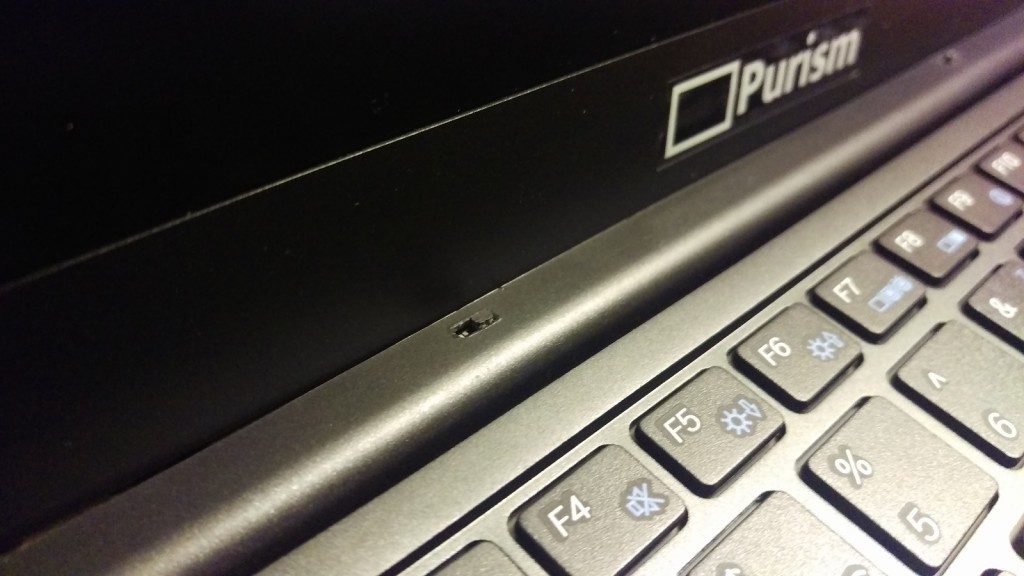

Do any computer cameras with “off” switches (not just covers) exist? They seem to be very rare at best, but I was able to find one: the company building a Linux phone, Purism, has a whole page devoted to the joys and wonders of its off switch—which is kind of ridiculous, if you think about it. The humble “off” switch is now high technology. It is a significant selling point for the single device that I could find that comes equipped with one.

(By the way, I have absolutely no relationship to Purism. I write about them because their focus is privacy and I’ve been writing a lot about privacy.)

Your phone has the same problem, you know

Tape over the webcam? Covers to disable the functionality we paid for? Why on earth do we go to these lengths when hardware vendors could simply sell their products with off switches? The more I think about it, the more I find it utterly bizarre. Don’t these companies care?

I’ve just been talking about webcams, but let’s talk about the really horrible spy devices: your smart phone. Oh, your Android phone can’t be hacked? Here are some handy video instructions, viewed over 300,000 times and upvoted 1,100 times. Surely not your iPhone? Don’t be so confident; hackers are very creative, as (for example) the Daily Mail has reported, and besides, Apple is proud of its patent allowing remote control of iPhone cameras.

Besides, it’s been known since at least 2014 that the NSA had developed, as early as 2008, software to remotely access anybody’s phone.

And yet there isn’t a hardware off switch for your phone’s camera and microphone, short of turning the device entirely off (but there’s an app to turn the camera off). A device equipped with a hardware “off” switch for the camera and microphone isn’t yet on the market, as far as I know. Purism is making one.

It’s not just your webcam and your phone that you need to worry about, by the way. Do you have a smart speaker? At least you can mute Amazon Echo’s microphone, and it’s apparently a hardware switch, too, so well done, Jeff Bezos. That’s important, if true, because it prevents software exploits. I found no word on whether Google Home’s and Apple HomePod’s mute buttons are hardware switches; maybe not. How about a surveillance or doorbell camera? How about your smart TV? Those can be hacked too, of course, and some of them are always listening. Wouldn’t it be nice to have the peace of mind that they aren’t listening to you when you’re not using the TV?

In short, what if you want to turn these devices’ cameras and microphones off sometimes, for some perfectly legitimate reason? Can you do so in a trustworthy, hardware-based way? In most cases, for most devices, the answer is No.

Let’s demand that hardware vendors build hardware “off” switches

It’s almost as if the vendors of common, must-have devices want to make it possible to spy on us. An enterprising journalist should ask why they don’t make such switches. They certainly have deliberately made it hard for us to stop being spied upon—even though we’re their customers. Think about that. We’re their bread and butter, and we’re increasingly and rightly concerned about our security. Yet they keep selling us these insecure devices. That’s just weird, isn’t it? What the hell is going on?

But this, you might say, is both paranoid and unfair. Surely the vendors don’t intend to spy on you. Why would they add an off switch when nobody will turn your camera and microphone on without your consent?

But, as I already said, it’s a hard, cold fact that hackers and government and corporate spies can and sometimes do turn our cameras and microphones on without our consent. This isn’t controversial and, for anybody who is slightly plugged-in, shouldn’t be surprising. Security experts have known that, for many years, regardless of the intentions of hardware vendors like Logitech and Apple and large software vendors like Skype and Snapchat, the hardware, firmware, and software that run our devices just are susceptible to hacking. It’s just a fact, and we are right to be concerned. So these companies are responsible for building and selling insecure systems. At a minimum, they could be made significantly more secure with a tiny bit of hardware: the humble “off” switch.

If your webcam, or your phone, or any other device with an Internet-connected camera or microphone (think about how many you own) has ever been hacked, these companies are partly to blame if it was always-on by design. They have a duty to worry about how their products make their users less secure. They haven’t been doing this duty.

It starts with us. We the consumers need to care more about our privacy and security. We’re not powerless here. In fact, we could demand that they give us an off switch.

I think we consumers should demand that webcams, smart phones, smart speakers, and laptop cameras and microphones—and any other devices with cameras and microphones that are connected to the Internet—be built with hardware “off” switches that make it impossible for the camera and microphone to be operated.

Do you agree?

Leave a Reply