Anti-natalism is the view that that human beings should not have children, because it is unethical to do so. Different reasons can be offered for this startling position, but the position I discuss in this essay specifies that life has negative value for those burdened by it. It is more bad than good, or the bad that there is in life is somehow more significant or weighty than the good.

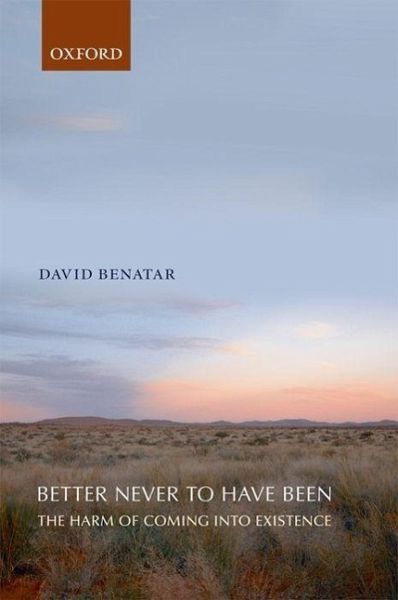

Perhaps the best-known anti-natalist, David Benatar, maintains that since life includes suffering and nonexistence does not, and since nonexistence has nothing bad about it—he is much impressed by this “asymmetry,” i.e., that suffering only occurs for life—it follows that nonexistence is preferable to life. But since it is impossible for parents to obtain consent from their future children for their coming into life (this looks like nonsense, as I will explain), we are imposing that pain onto our children without their consent. Anti-natalists can often be found blaming parents for all the suffering that their children ever have.

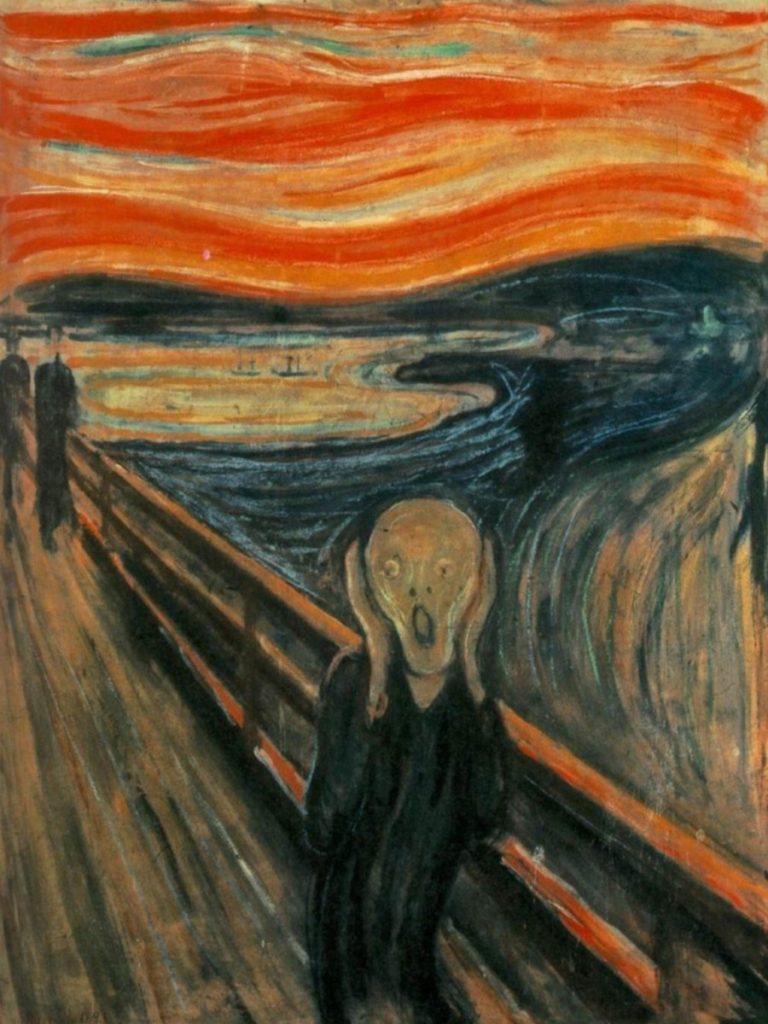

I will be honest: it is hard for me to take this view seriously. Moreover, I have little taste for pretending to take it seriously. On my view, any more elaborate or precise versions of the foregoing arguments do not make them any more plausible. The arguments are simply awful, and their social consequences strike me as deeply pernicious. Still, a few people reading this might disagree with me: maybe you think anti-natalism needs a hearing; maybe, even, it sounds plausible. If that is your reaction, after reading the previous paragraph, then I suspect it is not because of the excellent quality of the arguments. It is probably because it appeals to your more basic pessimism—perhaps a pathological condition. After all, we are talking about about a view according to which no one should ever have children because life is just that terrible.

In this brief essay, I will try to refute anti-natalism in the sense defined above. It is very possible that my arguments will not address or refute versions of arguments that some people have come up with. But they will, I hope, address some common versions. In any case, bear in mind this just an essay, an attempt, not a carefully-formulated position paper giving my final word on the subject. I might update this if conditions warrant.

As I understand it, there are two main parts to the case for anti-natalism. First, there is the part that says that it is morally wrong to foist a life of suffering onto children without their consent. Second, there is the premise that the suffering inherent in human life makes it indeed worthless, or worse than worthless. Both parts seem necessary. If human life were a good thing, then it would not be so objectionable to give life to new people. And simply claiming that human life is worthless does not clinch the case unless you draw the further conclusion that parents are doing wrong by creating worthless life (or life with negative value).

So I will take these two parts separately, beginning with:

The Question of Consent

The very idea that unconceived children have a right to consent whether or not they wish to be born is, of course, strictly nonsense. If something does not exist, it has no rights, no wishes, and no way to assert rights or wishes. Indeed, it makes no sense to speak of “it” at all; the pronoun stands for a posited individual which does not exist yet. Some people (who do very much exist today) point a finger of blame at their own parents: “I had no say in this life; I was not consulted,” they say. The answer is straightforward: “You could not have been consulted, because you did not exist yet.”

My answer leaves anti-natalists unimpressed. They are determined to blame their parents for making the bad choice of birthing them: there seems to be real resentment there. “You did decide to give birth, and the person you gave birth to happened to be me. This was a bad move and I resent it. You took this action, and it resulted in a life, which just happens to be my terrible life.”

If this is to be the line, then it is pointing toward a slightly different argument. After all, the original argument was supposed to be that parents did not obtain consent from their as-yet unconceived children, and parents have no right to consent on their children’s behalf. But that argument really is nonsense. “Ought” implies “can”: if I ought to obtain consent from my future children, then I should be able to obtain consent from them. But as this is a metaphysical impossibility, it is not the case that I ought to obtain consent. At the time, there is no one to obtain consent from.

But if the argument is, instead, that parents make a poor choice generally by bringing a sad new life into this vale of tears, then no mention of (impossible) consent need be made. Then the idea is that the parents are doing something that has bad effects; the anti-natalist has, essentially, a consequentialist argument, i.e., one about the goodness or badness of consequences. People experiencing existential anger at their parents feel personally affronted because they are the recipients of these purportedly bad consequences.

But then the strength of the blame we assign to parents depends on the strength of the argument that life is worthless; on that, see the next section.

Even if, contrary to fact, some sense could be made of the notion that parents are making a decision for their children which they have no right to make, we can simply deny the latter: parents decide things for their children all the time, after all. Parents raise children in a particular place, teach them a particular language, send them to a particular school, raise them in a certain religion, punish them for doing wrong and reward them for doing right, and so forth, all without consulting the children. The law recognizes this right. Reasonable people can, of course, disagree about specific cases; parents do not own their children, and they do not have unlimited authority over them. But one particular area of authority rests in the basic right to have children in the first place. The law certainly recognizes procreation as a basic, fundamental human right.

Admittedly, this is just a legal right, however; if to be born is to be harmed, then perhaps a moral right has been violated. That remains to be hashed out in the next section.

I want to make one further point on this head: the argument (again, that we should not have children because doing so does not respect their autonomy) proves too much, as philosophers are wont to say. Consistency on the point has some decidedly unpleasant consequences that could make anti-natalists look like monsters.

Let us agree, just for the sake of argument, that adults should never have children. But life sometimes throws us a curveball: suppose a gal gets knocked up. What is she to do? Well, if she decides to have an abortion, is she not making a decision on behalf of her child, just as much as if she were to bring it to term? It is misplaced to insist on the word “fetus” in this case, by the way: anti-natalists go far beyond pro-lifers, who talk about the rights of unborn persons, to claim that nonexistent persons have rights, or at least the right to consent to come into existence.

Let us suppose the anti-natalist advises her to get an abortion. After all, that baby has not given consent. Very well. But if, before conception, there is a hypothetical person there with a right to consent, surely after conception there is a person there with a right to life. Which right—the right to deny consent to exist, or the right to live—should prevail? The anti-natalist is faced with a dilemma. Either there is a person with rights there, and hence a right to life that must not be violated, or there is not. It will not do to say, “Well, that mother should not have conceived.” Let us suppose she has conceived; that is just a sad fact. This dilemma must not be ignored. Its existence does not imply that anti-natalism is wrong, but it does make it hard to be a consistent anti-natalist, for abortion rights advocates anyway.

The problem is this. If you (i.e., an anti-natalist) think a child has a right to consent, then immediately after conception at least it certainly is capable of having other rights. If, in that case, you conclude that abortion is justifiable, then you are in effect denying that this growing human life has a right to life. One way out of the dilemma is to bite the bullet and find some reason to deny that this person, who has at least one other right, has no right to life. And, come to think of it, the anti-natalist does have a reason ready to hand: if life really is worthless, perhaps we should reconsider the very idea that there is a right to live, at least for the very young.

In that case, the dilemma is not over. Suppose the mother decides to have the baby after all, and now it is one year old. The baby still has not given consent, of course, and the usual human suffering has already started (e.g., colic). By the anti-natalist’s lights, is the mother perpetrating an ongoing harm to her baby, by continuing to support it? It certainly seems she is. After all, if bringing a child into existence harms the child, then surely continuing to care for the child does as well. Should she not, in that case, snuff out this nonconsensual life? Why not?

The idea fills us with moral horror, of course, or it should. But what resources can the anti-natalist bring to bear to avoid the consequence? From the point of view of a philosopher considering that life is worthless, and that the child has not consented to live, there really is not much difference between a newly conceived child and a one-year-old child. Both are lives that should not have been, according to the anti-natalist. If you could abort a newly-conceived fetus because (despite having other rights) it lacks a right to life, then why would it have gained a right to live by the very tender age of one?

The anti-natalist might say, “But there are other reasons we would not commit infanticide. Obviously we cannot have people going around killing babies.” Yes indeed, well spotted. There are other reasons. But the anti-natalist cannot help himself to those reasons, because they generally presuppose the value of human life, and human life, especially the life of the very young, has no value—remember?

You cannot rest on the comforting practices and beliefs of civilized society as it is now constituted to escape these moral horrors—not without abandoning the premises of your position. If you begin to tell me about the comfort the baby feels in her mother’s arms, or the joy the mother feels in her baby, I will remind you that none of that seemed to matter when you were advocating against birth in the first place. Such maternal joys were, after all, perfectly predictable.

To bring out this point, I imagine a secret anti-natalist cult—a colony on a desert island, say. Everyone there is an anti-natalist, all planning to die childless. But some of these are young people and, of course, nature will sometimes take its course. The mother (nature intruding, again) opts not to have an abortion, and to the horror of the island cult’s anti-natalists, a child is born.

In such a society, “enlightened” as it is by anti-natalist sentiments, I imagine there would be an immediate demand to kill the child—humanely, of course. After all, that child did not choose to live; its mental capacity is unequal to a dog’s. On what grounds would the anti-natalists—far from the “corrupting” and “unenlightened” influence of broader society—choose to preserve the life of the child? Perhaps a right to life; but most anti-natalists will be fine with abortion, of course, so that theoretical expedient seems unavailable. No one who understands the issues wants the baby to endure a life of suffering. The baby can die peacefully and painlessly—and so, one imagines the anti-natalist cult concluding, in its “enlightened” wisdom, the baby should die.

But then, one wonders why they, themselves, would choose to continue living, but that is another question, to consider below.

The Value of Life

In another essay I argued that the value of life is intrinsic, i.e., human life itself just is that in virtue of which everything else is evaluated. I am not going to argue this claim much further here, except to point something out: the reason pleasure is good, when it is, is that it is the natural biological response to a life well lived. But sometimes, pleasure is very bad indeed, as when we are motivated to gain pleasure from activities that will kill us (as for example in drug addiction). Similarly, there is a reason suffering is bad, namely, it is the natural biological response to harm to the organism. Sometimes, however, the painfulness of suffering means no such thing. The suffering we endure from exercise is often a sign of a healthy activity. The suffering a rescuer endures from saving lives belies the notion that all suffering is bad: enduring it can be courageous and heroic.

The point is that pleasure and pain are imperfect qua signals of whether life is lived well or not. But ultimately the thing our pleasures and pains—and our bodily and cognitive systems, needs, desires, and in short the operation and flourishing of our entire human nature—aim at is the preservation of our lives and more generally of life wherever it is found. (I add the “more general” point because sometimes, arguably, we have biological urges to preserve someone else’s life, as when a parent risks all to save a child.)

I have gone into a bit of detail about this in order to clarify why, as I will now maintain, the anti-natalists’ notion of the value of human life frequently seems desiccated.

“We live only to be faced with an often painful death, and typically after a whole lifetime of suffering,” these pessimists intone. “Suffering is always much more awful than pleasure is pleasant. Pleasure really can be understood as the satisfaction of needs, i.e., the filling of a void. What is the significance of the mere absence of a negative in the face of profound suffering?”

Now, if this line of thinking is supposed to justify the conclusion that it is wrong to have children, it can only be through an intermediate conclusion, because it certainly does not follow immediately. Let us concede that life is a 100% fatal condition, that death is often painful, that suffering is often more intense than pleasure (not always—there are “peak moments,” after all, that some people sometimes say they live for). Now, it seems to me that the needed intermediate conclusion is that life is worthless, or worse than worthless; or, to put it more simply, not living is preferable to living.

Benatar and many anti-natalists are constantly found assuming the truth of this claim, but it strikes me as not just (a) unsupported by the weak premises, but also (b) quite obviously false. Let us consider the latter first.

Not Typically a Vale of Tears

Take the latter point first: it seems obviously false to say that not living is preferable to living. Most of the time, most people find life to be worth living, not merely a “vale of tears.” Various surveys of “average happiness” have been conducted around the world, and with few exceptions, on average, people in most countries are more happy than not.

Older folks are, typically, filled with regrets about mistakes and missed opportunities; but rarely do you hear them regret having lived at all. If they say, “What has it all been for?” it is because they feel they have not been productive enough, or maybe because they have left no family behind. Sometimes it does enter into their calculus that their life was filled with physical and emotional suffering. But few lives are burdened by unremitting suffering. There are, of course, exceptions, i.e., people who are depressed or miserably schizophrenic their whole lives long, or whose bodies were never-ending sources of pain. But the portion of humanity that fits into those categories is small.

How do anti-natalists respond to this? There are two ways to respond. One is to look down upon all those small-minded happy people with contempt. Happy people are living a lie. This strikes me as arrogant and, in any case, unpersuasive. One common reason is for such arrogant pessimism is the observation that we will all obviously die eventually. It is supposed to follow from this that our lives are meaningless and pointless. That has never struck me as being a good argument. It is a stance some anti-natalists take, but, in short, I think there is no way to defend it. After all, the value experienced in a life clearly has a time limit, this is well-known to everyone but the young and foolish, and yet people continue to find meaning in that value. A mother might have only fifty years in which to love a child; but that love is certainly one of the things that gave her life meaning for those fifty years. Why not? Who is the anti-natalist to tell the mother that that love is meaningless just because it has an expiration date?

(There is, of course, more to say on this point, especially for the religious sorts who believe life and love do not necessarily have an expiration date.)

A second type of response has the anti-natalist realistically acknowledge that some people are happy, but the problem is that there is no way for a parent to know, in advance, if a child will end up being one of them. There is massive risk inherent in life—the risk of having a life of misery.

To this I reply that indeed, it is true that life is risky, and that some (I think few) people might justifiably conclude, in their own cases, that it would have been better never to have been born. Given that, it seems parents must be courageous on behalf on their children, so to speak—a concept that I think will be perfectly familiar to parents. There is a kind of existential courage every new parent ought to muster: making the most of a new little life in the face of possible disasters is a very big responsibility. Then, a part of what it means for the child to grow up is to accept the mantle of that existential courage on one’s own behalf. It is cowardly to reject that mantle. When we want to admonish a young person who seems to be cowardly in the face of this existential challenge, the usual thing to say is: “No one said life would be easy.”

This is not to deny that, sometimes, the challenge is beyond a person’s power. If you have a disease that leaves your body racked with pain, and there is no end in sight, no one will blame you terribly if you declare you want to give up. Fortunately, life is rarely so awful. If you have a typical life, with typical diseases and typical heartbreaks, you are better advised to get up the courage that a typical life requires.

In any event, to argue that parents should not have children because they might have a life of misery is to counsel the opposite: cowardice. And as far as I can see, the mere risk of disaster is by itself an obviously terrible argument in favor of such cowardice.

The Bad in Life Is Not More Profound than the Good

We were discussing the anti-natalists’ key claim that not living is preferable to living. My first response is to point out that this is unpersuasive; indeed it simply seems false (and cowardly). My second response is that the anti-natalist is guilty of a rather obvious non-sequitur. Clearly it does not follow from the ancient platitude that life is a vale of tears (something poets, prophets, and philosophers have told us for millennia) that life is not worth living (a view the same sages rarely endorse). It seems one hardly needs to say more than that. It simply does not follow from the patent and prosy fact that life kind of sucks sometimes that life is not worth living.

The fact that it is such an obvious non-sequitur is probably why David Benatar felt it necessary to bolster that patent and prosy fact with what sounds like a very logical, technical, and irrefutable argument. To wit—living and nonliving are asymmetrical, he correctly points out. Or rather, he is correct just insofar as the former features something decidedly bad (viz., suffering), while the latter has nothing either good or bad in it. Benatar also, curiously, wants to insist that nonliving lacks suffering, and that is good; but I will not admit this feature, because something nonexistent cannot have either good or bad features.

The problem is that the anti-natalist conclusion still does not follow, even given Benatar’s observation about the living-nonliving asymmetry, and for a few different reasons.

First, the asymmetry goes both ways. It is true that whatever is nonliving lacks suffering and other bad things, and that is all very well. But life has value in itself, as I said above, a value nonexistent things cannot have. Which asymmetry should we be more impressed by? The inherent value of life is a belief we have naturally, even despite ourselves; even animals of different species value the life they see in each other—enough, even, to rescue each other.

Even if you did not agree that life is valuable in itself, you must at least admit that life has all sorts of good aspects, and not just some vague unspecified pleasures, but love, truth, and beauty—the list can go on long. What of productivity, virtue, and worship? Only someone with an arid, hedonistic view of the value of life could possibly be intellectually impressed by Benatar’s argument if it is couched only in terms of pleasure. And only a pessimist, or someone with clinical emotional difficulties, could actually be persuaded by it.

After all, we rightly congratulate people for their new babies. We celebrate birthdays. We honor the dead and their lives in funerals. When we do this, we are not saying, “Oh, this person had some pleasure and on balance avoided pain.” The very suggestion is laughable—patently absurd.

Now, Benatar takes pains (so to speak), sometimes, to point out that by “pleasure” and “pain” he really means “anything good” and “anything bad,” and that he is happy to recast his argument in terms of most any value theory. The problem is that the asymmetry he insists on is really obvious only in the hedonistic version of the argument. In other words, we can perhaps agree with him that suffering is more intense and long-lasting than pleasure—i.e., when the goods are pleasures and pains. We cannot agree with him so easily that the bad in life (more generally) is more important or consequential than the good. After all, this is precisely why we undergo such painful sacrifice, sometimes, in our lives: in order to secure things that are more importantly good. Students will rack their brains and stay up many late nights in order to gain knowledge. New parents will go to great trouble for the well-being (not merely the pleasure) of a new baby. A soldier will sacrifice everything in a key battle, or undergo awful torture, for the sake of a cause he regards as much more important than himself, such as freedom. There is something shabby, contemptible, and cowardly in the suggestion that these reasons we have for living and even dying are somehow less important or profound than the the various troubles that life throws at us. Do Benatar and his followers not care about such things? And if not, why not?

Even those who are living with painful disease, the memories of abuse, or profound personal tragedy usually—with grim determination—admit that it is better for themselves and the rest of the world that they continue to struggle on. To dismiss such brave thinking is shabby. A few supposedly sober and serious philosophers do seem to dismiss it—such trials are a reason never to have children, they say. We more normally attribute such pessimism only to terminally depressed mental patients. Why should we expect there to be any good argument for it? Why should we be surprised when, upon examination, the arguments put forth are terrible?

There is a fact known to everyone facing life’s challenges with grim determination: some deeply important values are worth upholding in a full, rich life. Again, we live for family, knowledge, beauty (e.g., music), freedom, security, and much more: Christians add, for the glory of God. These values, which together comprise the value of human life, are incredibly profound and worth living for. They are worth risking pain. Hence no person inspired by any wise, far-seeing vision of the values available to our lives—values that are admittedly limited and all-too-human—can be persuaded by the anti-natalist conclusion.

Is Anti-Natalism a Death Cult in the Making?

So far I have merely been defending the value of new human life against attacks upon it by anti-natalists. Now I wish to take the offensive.

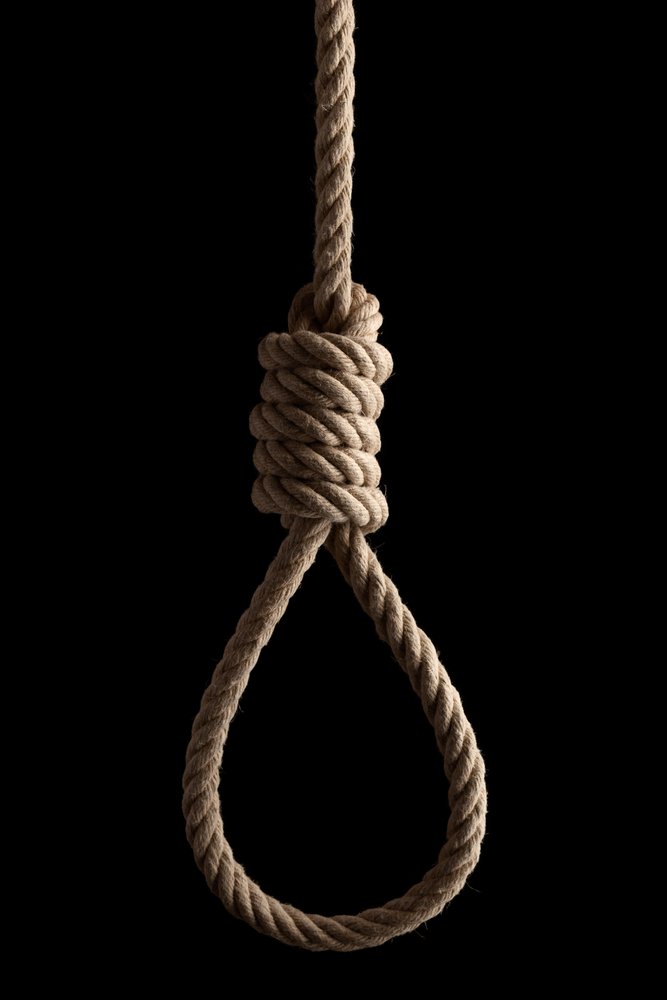

Anti-natalism is difficult to distinguish from terminal depression: its grim assessment of the value of life closely resembles that of a suicidal person. So one really has to wonder: why would a consistent anti-natalist not simply end it all? Death, or at least nonliving, is preferable to life, or so the anti-natalists maintain.

Benatar’s response is that killing yourself and dying are quite different from never coming into existence in the first place, which is easy to concede. To say that parents should not give birth to children is very different from the claim that you should commit suicide. True, acting on both will result in a person not living. But the difference is that killing yourself happens only after you have lived at least some of a life. Throwing that life away can be an awful thing, Benatar says—and, of course, he is very right about that—in a way that never creating a life is not awful at all.

Benatar is a bit too much impressed with this point, however, because it does not do the work he wants it to do. Before a new life begins, anti-natalists want to say, the suffering and risk to be expected in the new life are so awful that we cannot justify creating it. But if that observation is true, does it somehow change when a new person is born? Surely not. The suffering and risk we can anticipate in the life of a newborn is the same as that in a person who has never been born—or, for that matter, in a person who is 50 years old and facing declining health.

Very well. Benatar’s suggestion must be that killing—whether we mean a baby being killed (out of “mercy”), or a 50-year-old committing suicide—has awful consequences. There are fear and pain associated with the killing itself; grieving; the loss of support to a family, or the loss of future generations if a young person dies.

But if human life is so worthless that we can confidently tell in advance that it is not worth living, then what, really, is the loss once life has begun? If nonliving is better than living, then an enlightened anti-natalist would not fear but welcome death. The pain of dying can be minimized with drugs. Anyone who cared about a person who has died would not grieve but celebrate that another person has left this vale of tears, if they take the anti-natalist assessment of the value of life seriously. And while loss of support to a family is unfortunate, this is bearable; those still remaining usually make do. As to the loss of “future generations,” of course anti-natalists think that is a good thing, not a bad one.

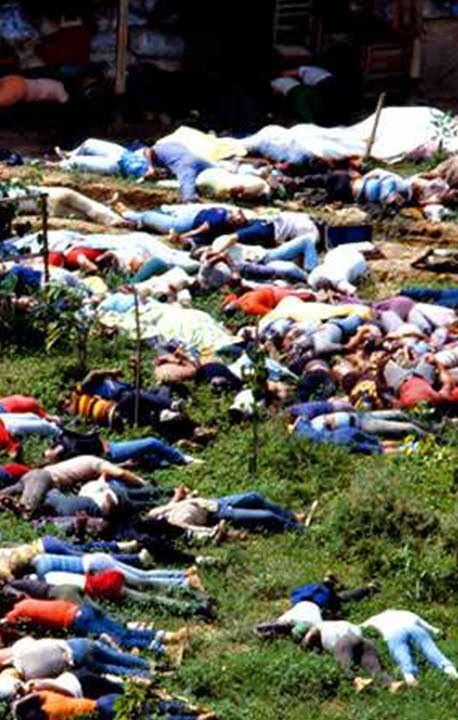

Let us return to the island with the secret anti-natalist cult. I speculated that cult would have no trouble with infanticide. But I would go farther to say that there is no reason to think they would not, if consistent anti-natalists, all eventually commit suicide; perhaps it would be a mass suicide, like a real death cult. Why not? Nonliving is preferable to living, and the cult members are already surrounded by like-minded people who will understand and properly celebrate their passing.

If you are an anti-natalist, you might well find this to be an insulting and silly thought experiment. You’ve probably heard it all before. If that is your attitude, you must take your own view more seriously. After all, why should you be able to help yourself to the attitudes of ordinary natalists, and of a society constructed by natalists, in defending an anti-natalist philosophy? What, will you say the reason you abstain from killing yourself is that you are part of a society in which doing so is considered impolite, wrong, and shocking? But that is the view of natalists. Your view is that it would have been better if you had never been born. That means that, if we compare a possible world in which you exist to one in which you don’t exist, the one in which you don’t exist is better. Given that bold assumption, why not assume that a world in which you are dead tomorrow would be better than one in which you stay alive as long as possible?

Is it because you can anticipate that, probably, the rest of your life will be adequately happy? Well, most conscientious new parents may make a similar assumption on behalf of their children, may they not? I just don’t know how you can have it both ways. Either human life is worth living, or it is not.

In any event, one thing that anti-natalists can agree on is that humanity should die out. After all, if our lives are worthless and no new humans should be born, then if we followed that principle consistently, humanity would be extinct in about 100 years. Anti-natalists are committed, therefore, to the incredibly ugly and indefensible proposal that mankind as a whole, all our works, everything we have ever produced, fall into oblivion. This might not involve any killing, but it is worse than anything Hitler, Mao, or Stalin ever advocated for.

Let us not forget that it is not exactly a leap from Benatar’s view to the view that we should all be put out of our misery. There are environmentalists and occultists who take exactly that view. They are not Benatar’s “philanthropic” anti-natalists, but “misanthropic” ones; but they share with Benatar the key premise, the radical and dangerous premise, that human life is worthless or worse than worthless, and that it would be better if the human race were to die out entirely.

I hope this makes it clear why I view anti-natalism as a thoroughly evil philosophy, and I mean this quite literally. There are not many philosophical views one can say that about. But it should not be surprising if anti-natalism earns the label. After all, it is opposed to the very thing that gives life its value—the preservation and development human life itself—and it literally displays profound contempt for human lives individually and for the entire human race. That fits the very definition of “evil” that I formulated last week, before writing this essay: “Evil is contempt for the humanity, the human life, of others.”

Leave a Reply