Philosophy and theology posit two kinds of self-sustaining beings: God, who is eternally self-sustaining, depending on nothing outside himself for his being; and living beings or organisms, consisting of many interoperative systems that function to sustain the whole, and which give rise to rough copies of themselves. Advances in robotics and AI now make feasible a third kind of self-sustaining being, which is neither God nor organism.

A zobot (Greek ζῷον, zoon, life; and robot) would have three distinctive features:

- It is self-guided by an on-board LLM, i.e., one independent of any networking or remote control.

- It is robotic, being able to move freely about and manipulate objects in the world.

- It is fully capable of maintaining its own systems in perpetuity, barring external physical damage.

The three features together make zobots self-sustaining. Together, the three self-sustaining beings—God, organisms, and zobots—share key characteristics. All three would be self-guided; all could move about the world, manipulating objects; and all would be capable of sustaining themselves in being, at least within an environment.

At present there are already many LLMs (which partly satisfy criterion 1) and many robots (which satisfy 2). And while modern robots routinely use neural net technology, none has yet debuted, to my knowledge, with an on-board LLM guidance system, which would fully satisfy 1 and 2 in the same machine. I will call these autobots (and to heck with the younger people and their Transformers movie associations; the word is just too useful). Despite appearances, “autobots” are not already in production; the dancing robot dogs, Tesla’s Optimus, and the like that you have probably seen online are guided by simpler (albeit very complex) algorithms and neural nets. Machines that have on-board LLMs that fully control all their capabilities would be a great advancement, and they are still in conceptual and experimental stages.

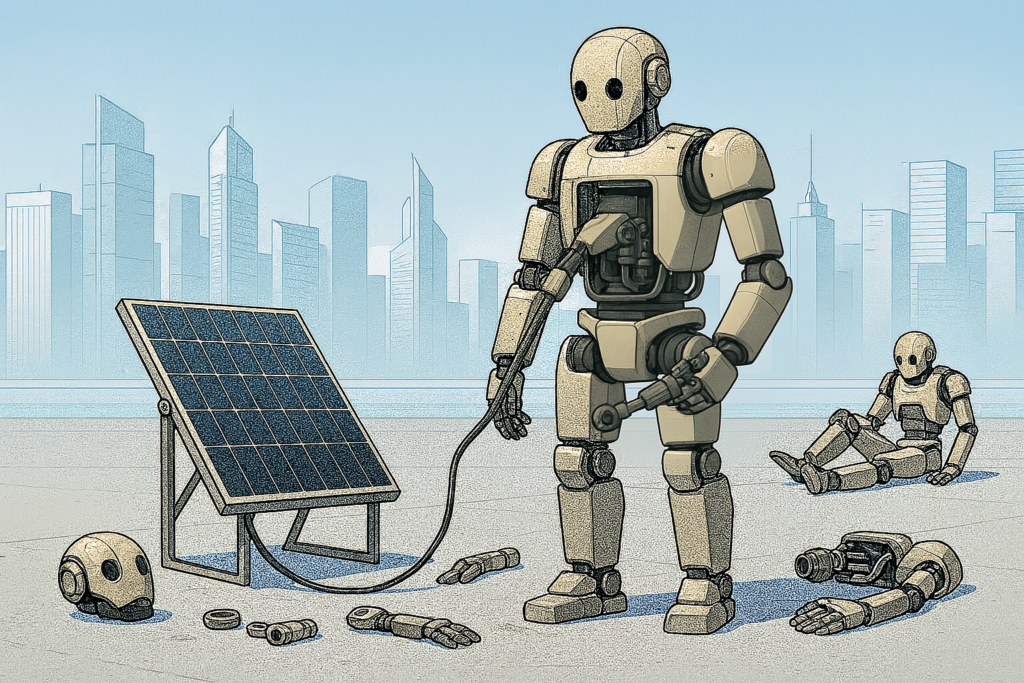

The first robots we will purchase will probably not have an on-board LLM. Eventually, however, we will see autobots, which do combine features 1 and 2; but even these will inevitably have to be maintained and repaired by human beings. No doubt this will remain the case for some time. We will not see any zobots—autobots capable of self-maintenance—until we have autobots that can plug themselves in, replace worn-out parts, and perform most repairs. Obviously, damage to the guidance processors or to the necessary motor controls would make self-repair impossible. Redundant systems, such as that imagined in Terminator 2: Judgment Day, would make totally irreparable destruction more difficult.

We can imagine zobots that “live” for centuries, regularly recharging; performing maintenance; backing up, performing downloads to, and restoring memory; and upgrading parts. Zobots could perform many “projects,” whether self-assigned or assigned by their owners. One thing that a zobot could do, whether by itself or with others, is build new zobots. In all these ways, zobots might perform many of the functions not just of living beings but of human beings in particular.

So, while the advent of increasingly capable robots will change our world, zobots will, doubtless, be even more revolutionary. They will confront philosophers with new philosophical questions, precisely because they are instrumentally intelligent (not to say self-aware or conscious) and self-sustaining beings in the world.

The very idea of a zobot raises some interesting philosophical questions, such as—

- Does the combination of an LLM type of “intelligence” with fully independent physical capability mean that zobots are persons? They might actually function in the world rather similarly to persons. Moreover, would a zobot be a being-in-the-world (in Heidegger’s phrase)? (Will they have genuine care, thrownness, and understanding?) If zobots are not quite persons, or beings-in-the-world, then do the differences actually matter? Why, or why not?

- Does the fact that a zobot is both “intelligent” and autonomous, capable of sustaining itself in perpetuity, constitute it as, at least potentially, a new kind of legal category, potentially even having a certain kind of rights? Can we imagine a “Robot Liberation Front” of 2100?

These are more metaphysical and moral-political questions. But there is another category of question that is unusually fascinating, which might be central to our reality in a matter of decades, and which might make the metaphysical and moral questions more pressing.

Presumably, zobots—more than plain robots—would pose a threat to human jobs. With enough iterations, anything that a human could do, a zobot could imitate, if not improve on. But let us stipulate that, after decades of advancements, zobots could build copies of themselves at nearly exponential rates, with the only cost being that of materials. Consequently, even if the first zobots were enormously expensive, it might be argued that the government—who through grants, contracts, and exemptions would have facilitated the creation of the technology—is obligated to supply at least some “seed zobots” and materials. This would be so that zobots could proliferate at a multiplicative rate (again, once the technology were advanced enough).

Once zobots were sufficiently ubiquitous, presumably, every household might have one (or more). While they might well do various jobs in the world, putting human beings out of work, it is interesting to consider that—if they were to serve essentially as tireless, self-feeding workers—they could theoretically grow enough food and other products to feed a family. But then, why would it not become the function of governments everywhere to run fleets of zobots that essentially provide all desirable items in practical quantities? Some in power might see such an age of plenty as a problem, and work to prevent it. Should they? This is a new kind of question for the political philosophers.

Others might point out that we would run up against limitations of energy and natural resources. Yet zobots could install and maintain the solar panels on roofs everywhere, so that the cost of energy dropped precipitously. And they could tirelessly sort through all the garbage, recycling as needed. But would that really still be enough for the demand? How would demand be managed in a world is crawling with zobots? What, indeed, would the economics of the new world be like? I have no idea, myself.

In short, while we might never discover free energy, zobots could provide essentially infinite, free labor.

But that, however, makes two very important assumptions: (1) zobots would not, in fact, have human rights, which we must respect; and (2) some nightmare scenario of self-aware AI would not seize the levers of civilization and, in effect, revoke all human rights.

The thing that strikes me most, however, is the very idea of a third kind of self-sustaining being in the world—moving among us, designed at first by us, and perhaps later by themselves, to do the sorts of things we do. We have not seen such beings yet, so I do not assume that they will exist. But at this point, it certainly looks as if they could.

Leave a Reply to Ian Hayles Cancel reply