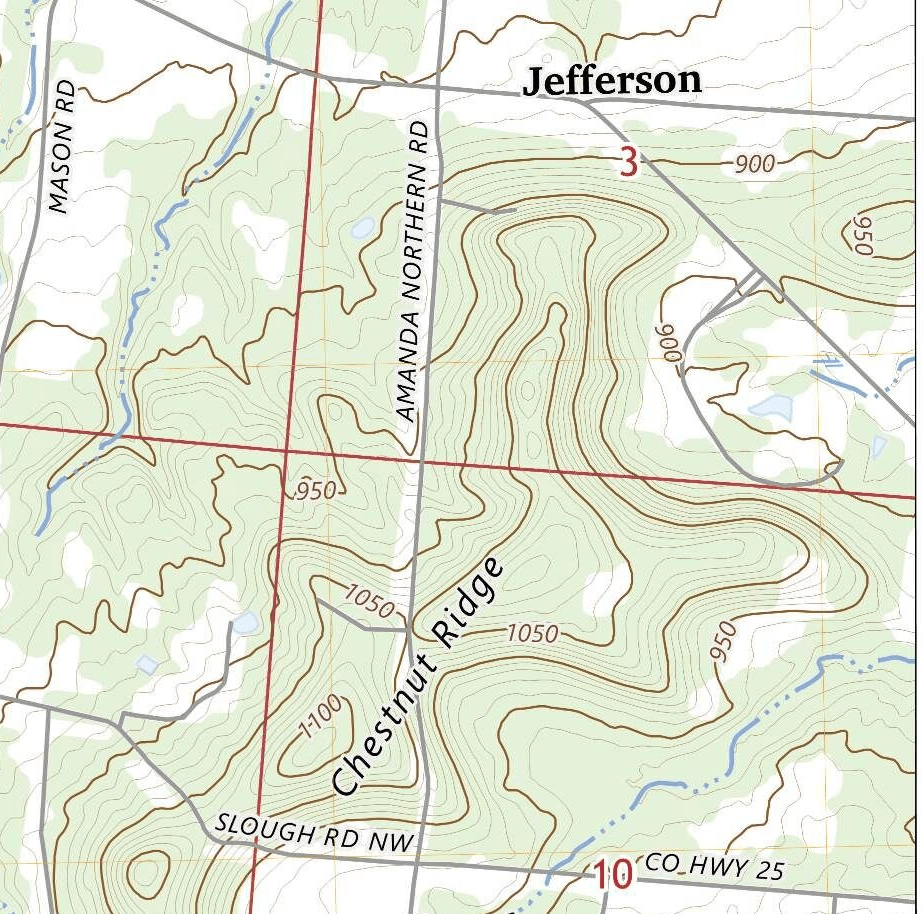

Chestnut Ridge Metro Park is a lovely woody park, offering miles of trails for hiking and mountain biking. It is located 16 miles southeast of downtown Columbus, Ohio. The park lies in Fairfield County, a couple miles south of the area’s main traffic artery, State Route 33, halfway to Lancaster. The park is about three miles southeast of Canal Winchester and five miles south of Pickerington.

The park’s main physical feature is the scenic Chestnut Ridge, the nearest protrusion of the Appalachian Mountains towards Columbus. The ridge lies about 200 feet above the parking lot and 350 feet above Walnut Creek, one mile to the north. The surrounding countryside is flat enough that the ridge can be seen for a few miles around. The high point in the park is 1,116 feet above sea level.

The park is divided into a larger section to the east of Amanda Northern Road and a smaller section to the west.

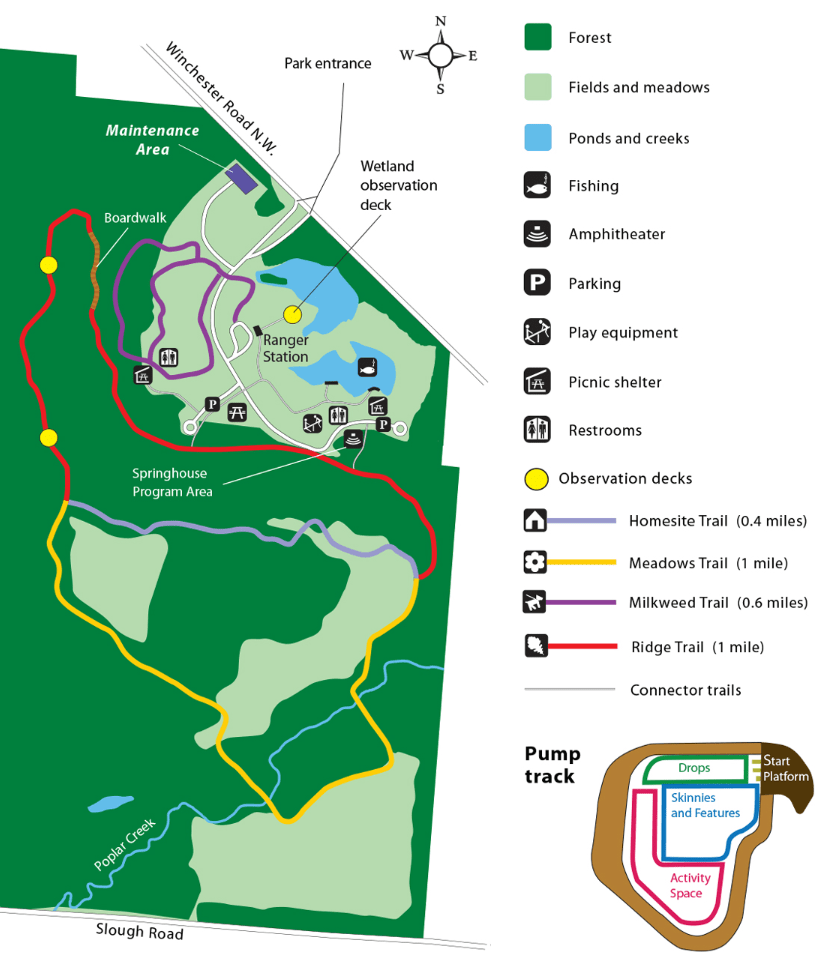

The park’s main attractions are its extensive hiking trails in the eastern section and mountain bike trails in the western section. The eastern portion also features a small fishing pond, a second, swampier pond with a birdwatching blind, playground equipment, and a small woodland lecture area. There are three miles of scenic hiking trails, according to the Metro Parks website, and perhaps another mile more of unnamed trails. In the western section, there are 10.5 miles of very twisty and steep mountain bike trails, leading to the highest point on the ridge. There are three parking lots on the eastern side and one on the western, with toilets (replaced in 2022-23, but without plumbing) at three of the parking lots. There are excellent picnicking facilities as well, with two covered shelters and picnic tables.

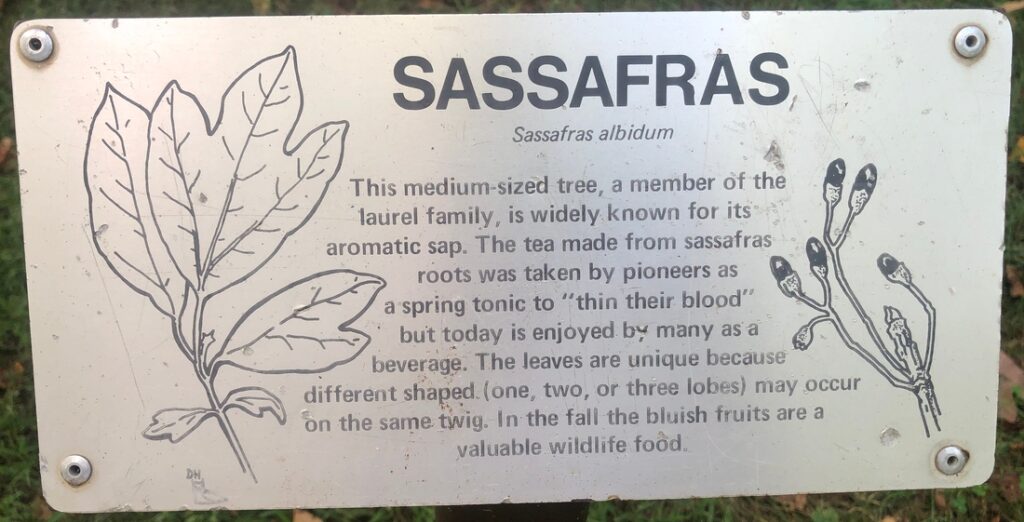

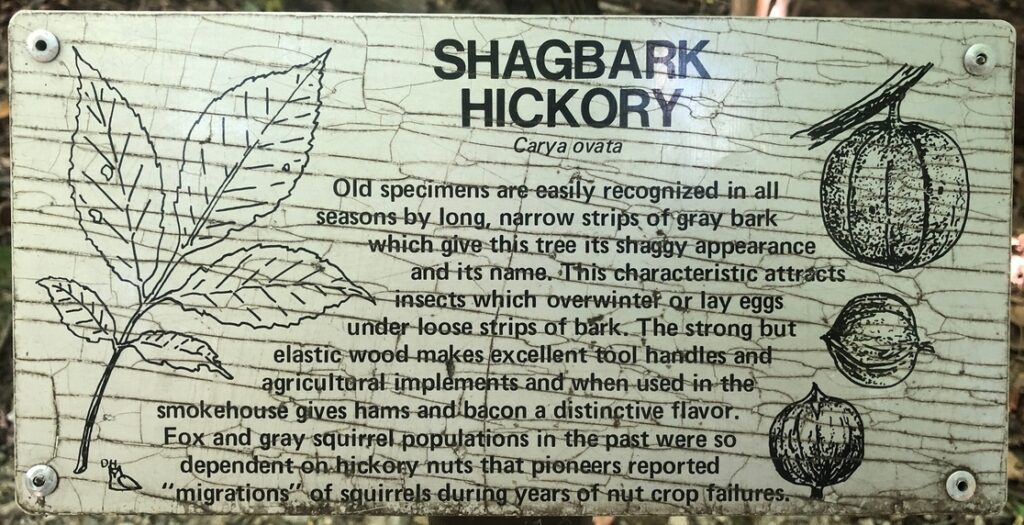

Wildlife typical of central Ohio can be seen in the park: deer, rabbits, tortoises in the ponds, hawks, and more. The fishing pond is stocked with bluegill, largemouth bass, and channel catfish.1 Frequently when the weather is nice, particularly near quitting time and on weekends, one may also spot walkers, often middle-aged and elderly locals, out for constitutionals, as well as joggers. The views and the enormous oaks, maples, hickory, and beech trees are perhaps the most interesting features, however.

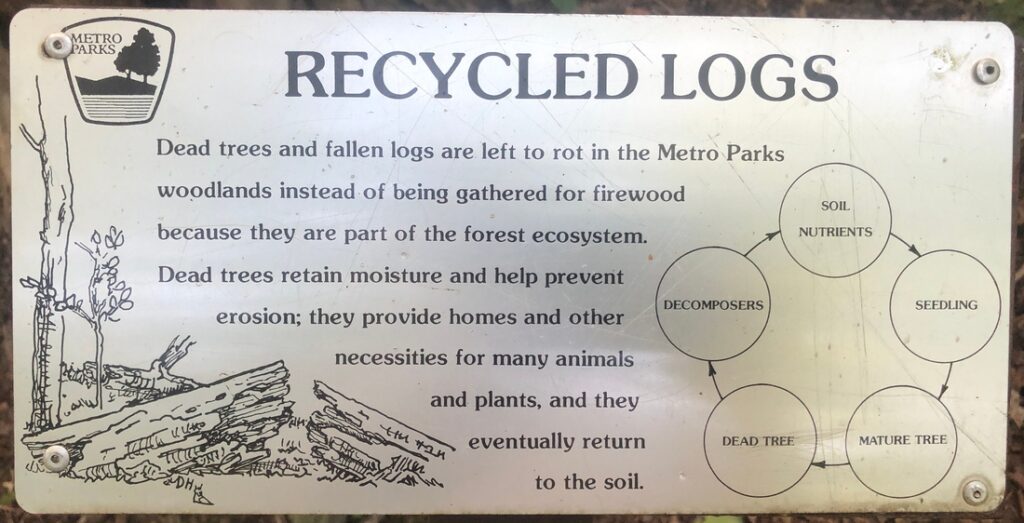

Metro Park policy has in recent years called for trees not to be cut up and removed but to be allowed to decompose where they fall. This policy follows natural forest management practices, which aim to regenerate ecosystems naturally. Leaving fallen trees or “coarse woody debris” in place provides habitat for various forest creatures, among other advantages.

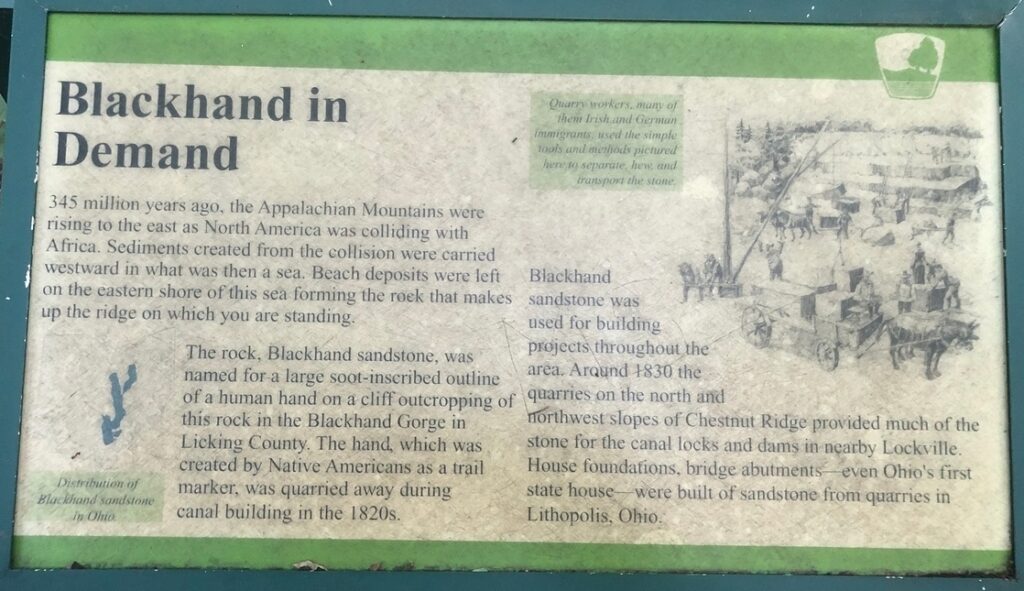

Geologically, the park is situated on a narrow outcropping of Blackhand sandstone “deposited more than 300 million years ago when Ohio’s ancient ocean drained from the land,” according to a Fairfield County park website. At least two small springs feed the ponds.

As is typical with Metro Parks, various ranger-led nature programs are held regularly. For these purposes, there is a small amphitheater east of the eastern parking lot, across a picturesque stone bridge; the area can also be used by Scouts, churches, and other groups.

Hiking trails

The Ridge Trail (1 mile) climbs close to the high point of Chestnut Ridge on the eastern side. The trail has the park’s best views of the woods, which are quite pretty throughout the year, featuring enormous oaks, maples, and hickory. The trail is entirely wooded, except for a couple of small clearings, and the temperature can be counted to be a good ten degrees cooler in the woods than out in the fields. A popular short, but vigorous, walk begins at the westernmost parking lot and climbs about 150 feet to two different observation decks. In years past, there was a nice view of downtown Columbus from the first deck, but trees have grown up to block the skyline except, perhaps, on clear winter days. The southern deck looks down through the trunks of a long forested slope. The view from both decks might be thought better in winter.

The climb up to the observation decks is deemed “moderate to difficult” by the Metro Parks, but it is over fairly quickly for most hikers. There is only one stretch that is rather steep, and there are benches for resting located conveniently after that. A few hundred yards of the upward path runs on a boardwalk that affords nice views eastward of the large trees and, in winter, of the ponds. Some hikers will go to the observation deck and then return. However, once on top of the ridge, the trail is much easier, though it continues up and down a bit. The lower stretch that the parallels the ridge, closest to the parking lots and ponds, is also fairly easy and flat. Hikers who make it to the junctions on either the west or the east side of the trail have the option to complete a loop: either the shorter Homesite Trail or the longer Meadows Trail.

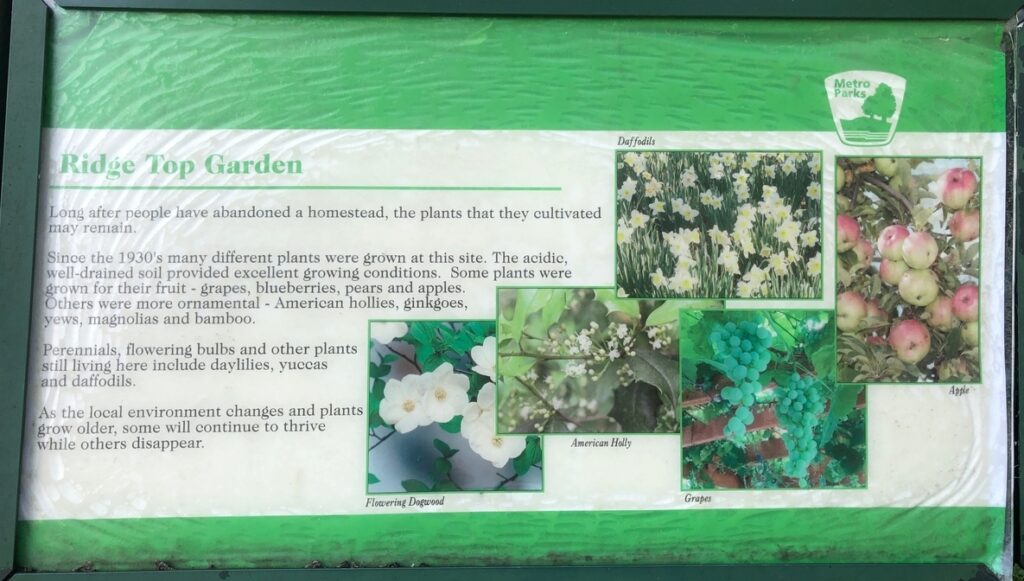

The Homesite Trail (0.4 mile) features one of the park’s more intriguing viewpoints: the foundations of an abandoned house, with a front walkway, yard, basement brick walls, and orchard still maintained to some degree. The house was one of at least seven that were found on park land in years past (see History, below), but which are all now gone and reclaimed by the park and woods. The house was pleasantly situated on the ridge, with a nice view down the long slope to the east-southeast. From this location, the nearest three neighbors were farms about 500 feet down the hill to the north, a thousand feet to the south, and a thousand feet to the east.

The climb up the ridge on the east begins on the Ridge Trail, then switches to the Homesite Trail while performing a 180° turn, and continues up to the homestead. The elevation gain from parking lot to homestead is about 140 feet, which explains the Metro Parks’ labeling the trail “Moderate to Difficult.” Again, there are benches for resting partway up and at the top. From the east, the trail skirts a former farm field that is being maintained as one of the park’s three larger meadows. From the homestead area westward to the other junction with the Ridge Trail is a much gentler climb along the ridge, past a sizeable stand of large coniferous trees and another, smaller prairie opening.

The Meadows Trail (1 mile) is so called because it skirts all three of the park’s prairie openings. It is unclear to what extent the three Chestnut Ridge meadows were prairie openings before settlement and farming.3 Regardless, these meadows are maintained as examples of aboriginal prairies by park staff; in addition to being occasionally mowed, nest boxes (see below) are erected here and there.

The trail begins on the east at a junction with the Ridge Trail, halfway up Chestnut Ridge. The trail skirts a meadow, descending to the south to a bridge over tiny Poplar Creek, then rising up again about fifty feet to the park’s largest prairie opening (see image above). As it executes a square-shaped route, the trail drops down to a second bridge across the creek. From there, the trail enters the woods (see image below) and climbs from one of the park’s lowest points to the park’s highest point on the hiking trail, an elevation gain of 170 feet. The stretch of trail is relatively long, so there are a couple of benches for rest along the way, and again the Metro Parks calls it “Moderate to Difficult.”

There are side and connecting trails throughout the park. These include probably over a mile of mowed paths through the prairie openings, but these paths can change from year to year. They are also frequently more uneven and thus harder to walk, especially if the grass has not been cut recently.

Three of the more interesting side trails, not marked on the official map, are old roads, or driveways, maintained almost as well as the main trails. All four are evidence of human habitation, not that long ago, on the ridge.

One of these runs two hundred yards or so to the west of the homestead and from there turns south for a half a mile; this was evidently the homestead’s driveway, shared with another farm. From north to south, it first leads between a prairie opening and the conifer stand, then crosses the Meadows Trail, Poplar Creek, and ends at the park’s southern boundary at Slough Road, where there is a locked gate. This is a pleasant out-and-back side route.

Off of the north end of the Ridge Trail, there is another pleasantly walkable old road, or driveway, that runs from a small meadow (see image below)—which itself was apparently the “packing house” for an orchard4—down the hill to the park’s northern boundary of Winchester Road (where, again, there is a locked gate). The walk out and back involves climbing down and back up the ridge.

A third old driveway runs west from the Meadow Trail, a hundred yards south from the junction with the Ridge Trail, near the top of the ridge. This trail runs southwest, to Amanda Northern Road (and another gate). To the north and across the road from this gate, there is another gate and old driveway that leads into the mountain biking area. There is a large old cut stone in the homestead at the top of this third driveway (pictured in the Geology section, below), apparently all that the park now shows of the farm located at this place; there is an informative sign along Meadow Trail showing the place (also below).

There are a few other trails, such as connecting trails from the fishing pond to the birdwatching blind (paralleling the drive) and the short Milkweed Trail through the grass near the park entrance (see the park map, above).

Chestnut Ridge Mountain Bike Trails

The western section is so separated from the eastern section (by a road, and with no shared trails) as to constitute a separate park. There are several named trails such as “Fireball,” “Squatch,” and “More Cowbell,” rated from Easy to Advanced. Note that “Easy” trails are not apt to appear “Easy” to those brand new to mountain biking. All the trails are twisting and narrow, as mountain bike trails can be, with many steep inclines and long descents, for a total of over ten miles of trails. As a result, many miles of the park trails are “for expert riders only,” according5 to the Central Ohio Mountain Biking Organization (COMBO), the organization that built the trails.

COMBO also reports that cyclists “should expect steep climbs, most notably a switchback climb up to the Apple Barn, followed by several flowy descents as you ride along the heavily wooded trail. A few bridges, banked turns, several log-overs, and a couple short sections of sandstone cobble can be found along this trail.” The advanced trail was rated the #1 mountain biking trail in central Ohio by trailforks.com.6

There is also a short and fun “pump track” not far from the parking lot (see diagram on the Metro Park map, above).

Geology

The park offers a window into local history that we will briefly review, beginning with geology.7

Geologists describe Chestnut Ridge as part of the Appalachians. It is an outlying knob of Black Hand Sandstone, a type diagnostic of Ohio. The sandstone stretches from the north to the south of Ohio and has since been mostly eroded. The famous Hocking Hills, of which Chestnut Ridge might be considered an outlier, were carved out of this same sandstone by erosion. During the last ice age, called the Wisconsinan advance, an ice sheet covered two-thirds of Ohio and reached up to Lancaster. The glacier surrounded, but apparently did not cover, Chestnut Ridge.8

A number of the properties that became park land “were leased for potential oil and gas production in the 1920s and again in the 1950s and 1960s,”9 but there was no drilling done on park land.

Archaeology

The park has some archaeological history as well. There is thought to be a mound called “Old Maid’s Orchard Mound” on the ridge in the western part of the park, and thus quite near the mountain bike trails.10 In 1986, in preparation for the general opening of Chestnut Ridge Metro Park, an archaeological firm was hired to perform a survey of the park. The survey found:

Subsurface testing and visual inspection of the project area located three prehistoric archaeological sites. Two of these sites are small, plow-disturbed lithic scatters which do not appear to be eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. The third site is a mound located several meters away from the proposed nature trail. The location of this site should be noted during the construction of the nature trail, in order to protect it from disturbance.11

The mound site that the report refers to here is apparently 5 meters off the Meadow Trail. It is located on the edge of the ridge, just south the high point of the eastern portion of the park. The report describes it as about 1.5 meters high and 10 meters in diameter, and it has (or had) a pot hole approximately 4 meters deep in the top.12 The author of this article has spotted a number of possible candidate contours in the land, but has not located the place definitively; there are no sign markers.

Numerous similar mounds can be found throughout Ohio, including much larger and more elaborate ones. These mounds are thought to have been constructed by two different ancient peoples, first between 1000 B.C. and 100 B.C. by people called the “Adena people” after the name of an Ohio estate where such mounds were found. The Adena are thought responsible for the well-known Serpent Mound in southern Ohio. After them, a different culture, the “Hopewell” people, also constructed mounds, including the extensive and remarkable earthworks in Newark, Ohio. Old Maid’s Orchard Mound is thought typical of the Adena people.13

History

Early settlement

Historical records appear to be largely silent about life on Chestnut Ridge, despite movements of Indians and scarce settlers in the early Ohio territory, until we encounter the land records of early 1800s. It fell to young Ebenezer Buckingham to perform the initial survey of the land that included Chestnut Ridge in 1801. As a history of the park puts it,

Buckingham commented on the timbered ridges with thin soil and with Chestnut and other timber growing. This is the ridge of current Chestnut Ridge Metro Park. The map accompanying Buckingham’s notes shows the “Road from Franklinton [i.e., the neighborhood across the Scioto from what is now downtown Columbus] to New Lancaster [evidently the town of Lancaster, Ohio]” running diagonally across section nine, and across one corner of section ten. Hence, there must have been a “road” of sorts before the first official settlers arrived in Bloom Township [i.e., the township in which the park lies].14

We also have the names of some of the early settlers in or near the park:

There is consensus in the published histories that the Courtrights, Hushors, Glicks, Hoys, Alspaugh (Alspach), and Thrash families were early settlers in Bloom Township. While they are not mentioned as early settlers Henry Orwig, Peter Robinault, and John Rockey, are either themselves buried, or have children buried in cemeteries near the current Metro Park area. Orwig, Robinault and Rockey were original owners of land in the sections of Bloom Township which are not in the Park.15

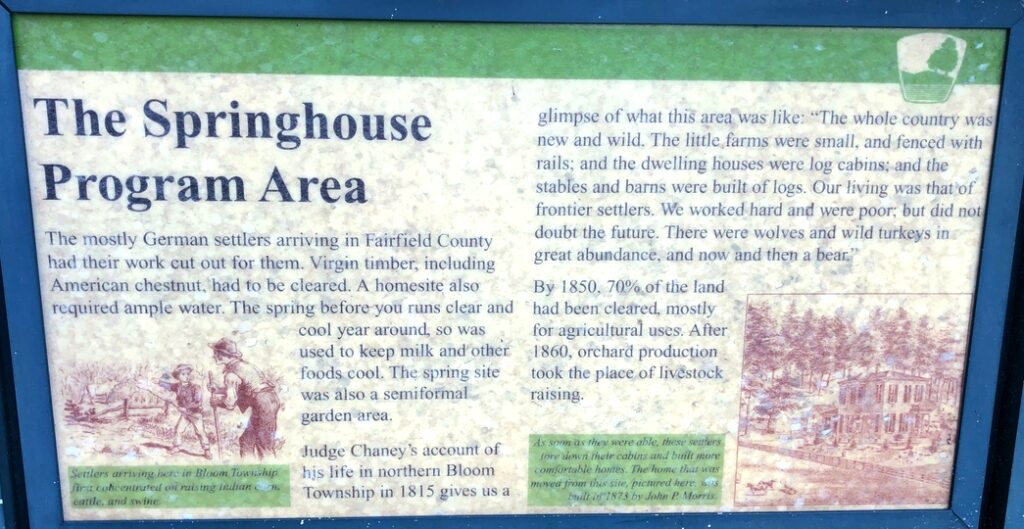

One interesting recollection of life near the park is by a Judge Chaney, who settled near the park in 1815. He wrote:

The whole country was new and wild. The little farms were small, and fenced in with rails; and the dwelling houses were log-cabins; and the stables and barns were built of logs.

Our living was that of frontier settlers. We worked hard and were poor; but did not doubt the future. . . . There were wolves and wild turkeys in great abundance, and now and then a bear. There were hawks of many varieties, which have nearly entirely disappeared; and the owls were hooting about the woods all the time.16

The agriculture of the area, in the earlier nineteenth century, included general farms raising corn with plenty of pigs and sheep, and some cows. Area farms became more focused on “horticultural production” (especially fruit orchards) after mid-century. By 1880, some 75% of park land was “improved.” The names of the farmers indicate the area was mostly settled by ethnic Germans from Pennsylvania.17

Life on the ridge in the first half of the twentieth century

One story of life on Chestnut Ridge is well-documented. It seems that, in about 1917-18, John Ovid (“J. O.”) Wagner and Catherine Cleland Wagner built a house and began what became a fairly large apple orchard, which spanned much of the top of Chestnut Ridge, and which featured some 40 varieties of apples. Their grandson recorded his memories growing up on the farm.18

There was also a stone quarry on park property “out on the point” (probably next to the northernmost point of the ridge itself, off the trail), and “two small workings on the top of the ridge,” probably for area home foundations.19 The author of the present article has found some rock debris and a deep ditch which might be the remains of one “small working,” on the slope just west of the eastern junction of the Homesite and Ridge Trails.

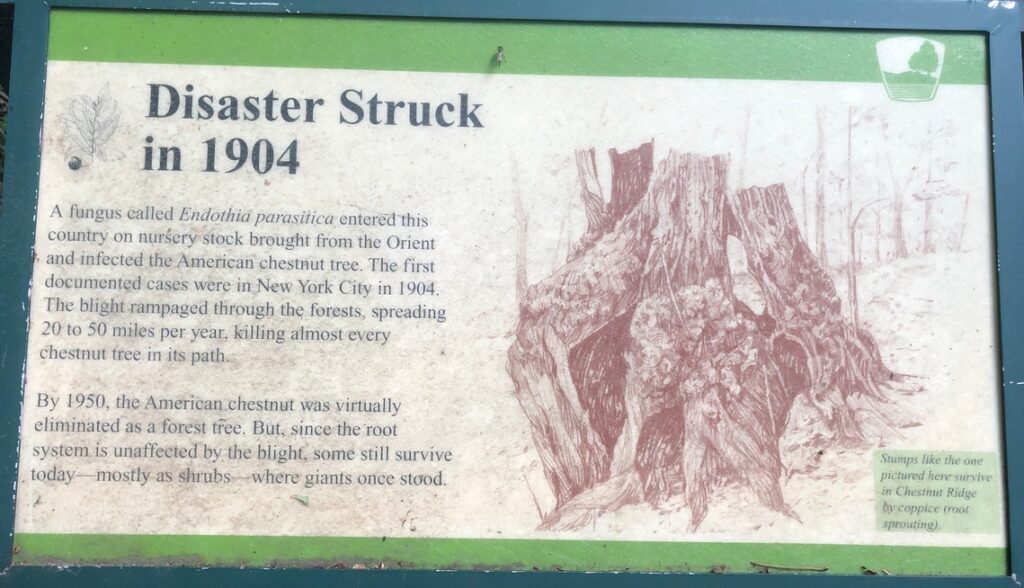

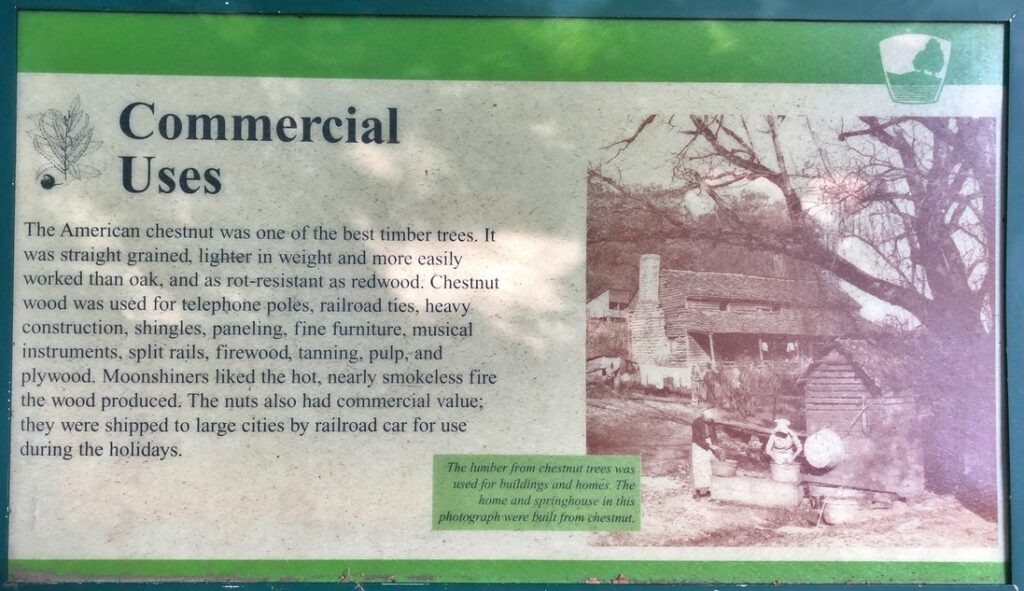

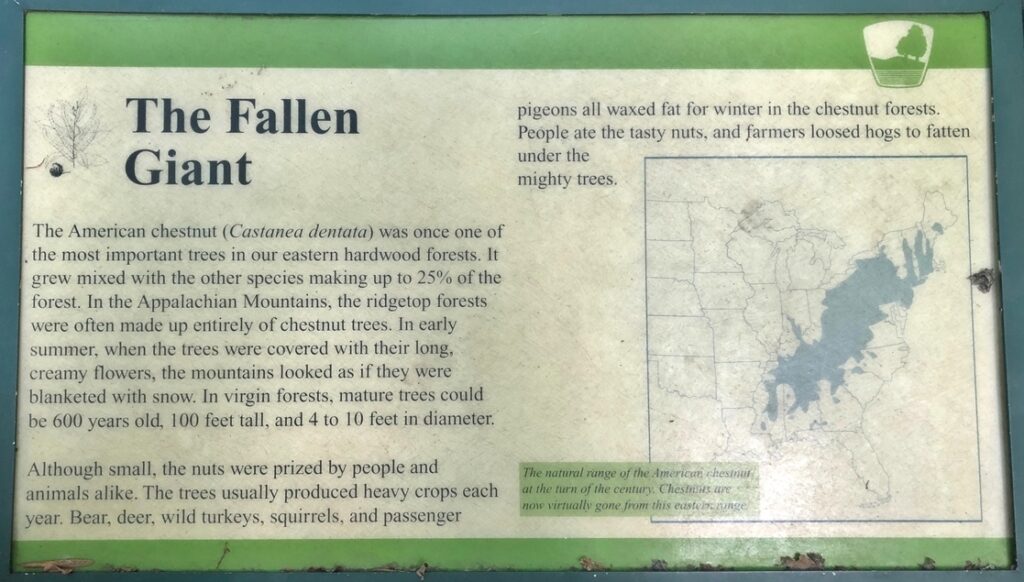

After that, a chestnut blight hit the ridge. The blight was first reported in the area of New York City in 1904. In the following decades, the blight devastated the grand old chestnut trees of the whole eastern portion of the country. The blight reached Chestnut Ridge in the 1930s and 40s, wiping out the old trees that gave the place its name.20 A county historian, Charles Goslin, wrote in 1956 that on Chestnut Ridge there were “only stumps, fallen trees and a few standing skeletons” of the once-great chestnuts.21 Attempts to revive the country’s old chestnut trees have not been widely successful; one source says the number of trees dropped from as many as five billion and that the present number is perhaps 435 million.22

An aerial photo from approximately 1955 (below) reveals a varied land usage of the park before the land was acquired by the Metro Parks. There were multiple residences and farms. The ponds did not exist; there was one residence close to the present park entrance, and another around the location of the eastern parking lot (perhaps due to the presence of the nearby spring; see image at right). All the area including the two parking lots, ponds, and relatively flat areas near the entrance (to the northeast of the ridge) were taken up by large farm fields. The northern arm of Chestnut Ridge was mostly covered with orchards. There was a sizeable farm where the driveway to the homestead crosses what is now the Meadow Trail; the farm buildings appear to be gone, but one clearing from the farm, next to the trail, is still mowed by park personnel. The ridgetop homestead which has the most visible remains is shown to have had a couple of outbuildings and a large circular driveway out front. McCormick quotes a document that speaks of a “three-car garage with servant quarters.”9 There were also fairly large areas, mostly on slopes, where it seems there were some older (not to say “old growth”) woods.

The emergence of Chestnut Ridge Metro Park

A park history records the names of the original government-assigned purchasers of Chestnut Ridge; in fact, no less than presidents Jefferson and Madison were apparently listed on the original deeds of sale.23 Thereafter, ownership of the park property, in different parcels, passed through a succession of hands. One parcel was sold by a Robert Heer to the Metro Parks on April 27, 1975; another, by Ervin and Erie L. Moore, on June 12, 1964; a small parcel, by Warren J. and Ora G. Moore, on April 8, 1966; another parcel, by Catharine and Glenn Laws, on October 18, 1973; and a final parcel, by Louis, George, and John Bovnig and their wives, on January 17, 1963.24

A review of the publicly-available topographical maps reveals that the park was labeled “Chestnut Ridge Park” in 1966,25 but not on the previous 1955 map. In an observation of the park in the 1970s, Goslin, the county historian, noted that park land was still “undeveloped” and still used as farm land.26

So, when can we say Chestnut Ridge was founded? It depends on what is meant. The Metro Park District of Columbus was created August 14, 1945.27 The first parcel was purchased in 1963, and the last in 1975. So, park land was held by the Metro Parks for about 13-25 years before the park opened.

Chestnut Ridge Metro Park was officially opened December 18, 1988 at 7 a.m.28 At the opening time, there was “a two-mile nature trail” and a “700-foot boardwalk.”

The mountain bike trails, spanning 7.5 miles, opened Sunday, October 16, 2011, at 10 a.m., and were inaugurated with a cookout.29

As of 2023, the park appeared to be both well-maintained and well-used. On fine afternoons, one can find dozens of people using the park’s trails and other amenities. The park continues to be well-maintained. The aging boardwalk was renovated in sections beginning around 2020. In 2023, two severe windstorms knocked down dozens of trees, some of them enormous and near the trail. The trees that fell across the trail were quickly cut and removed. In one place, near the western parking lot, so many trees fell that a new clearing was made. Doubtless, in ten years, younger trees will restore the shade.

The history of Chestnut Ridge is a fascinating window into the history of Ohio itself. While the land supported setters from the early days of the country, we can be grateful that it has been returned to a wilder state for our enjoyment.

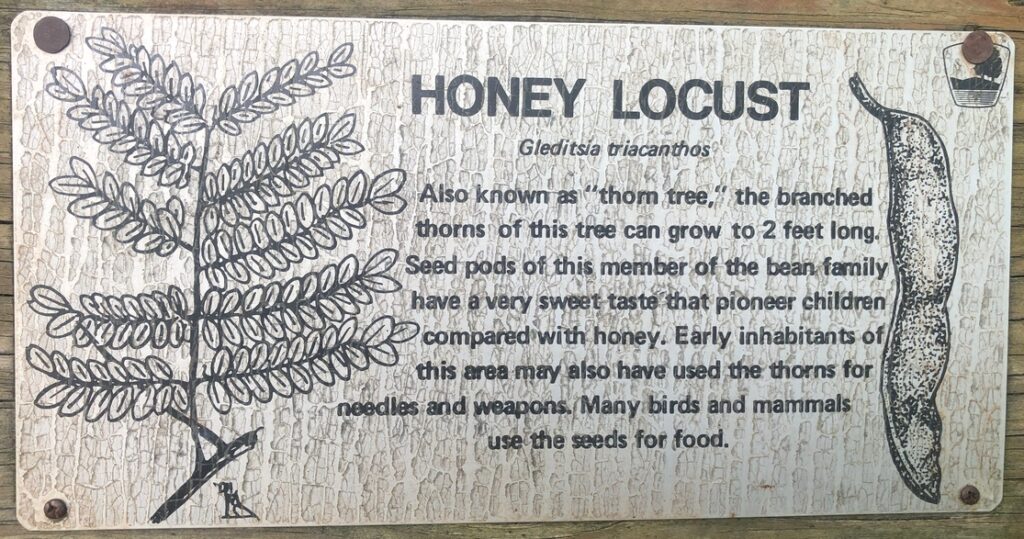

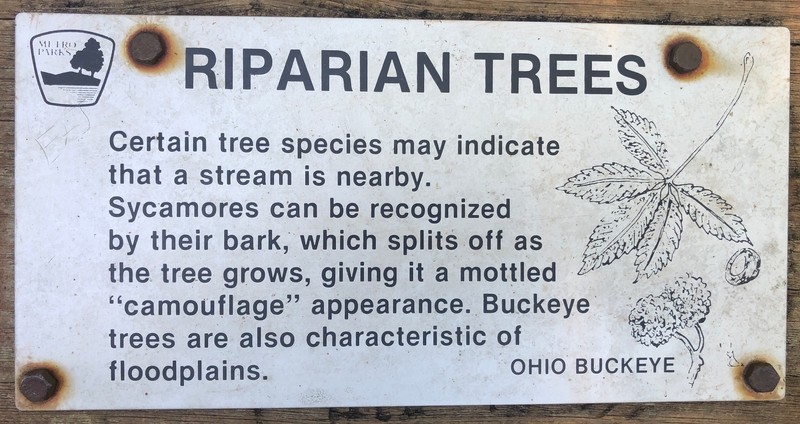

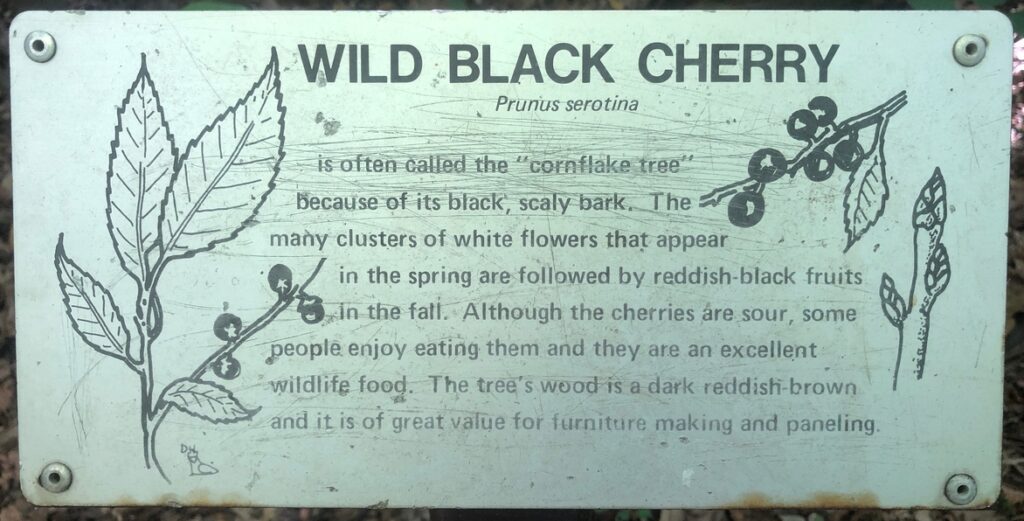

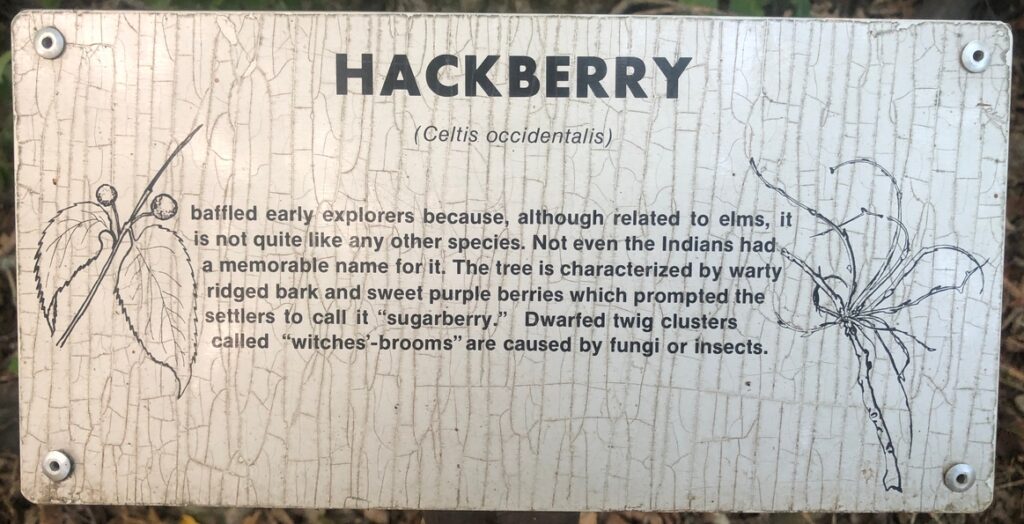

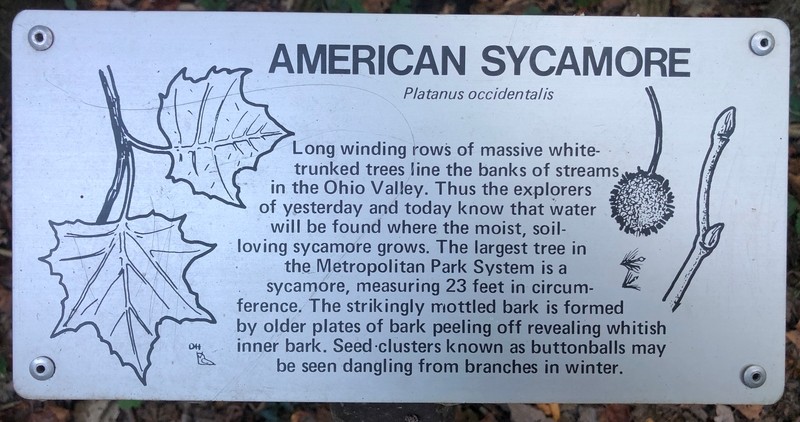

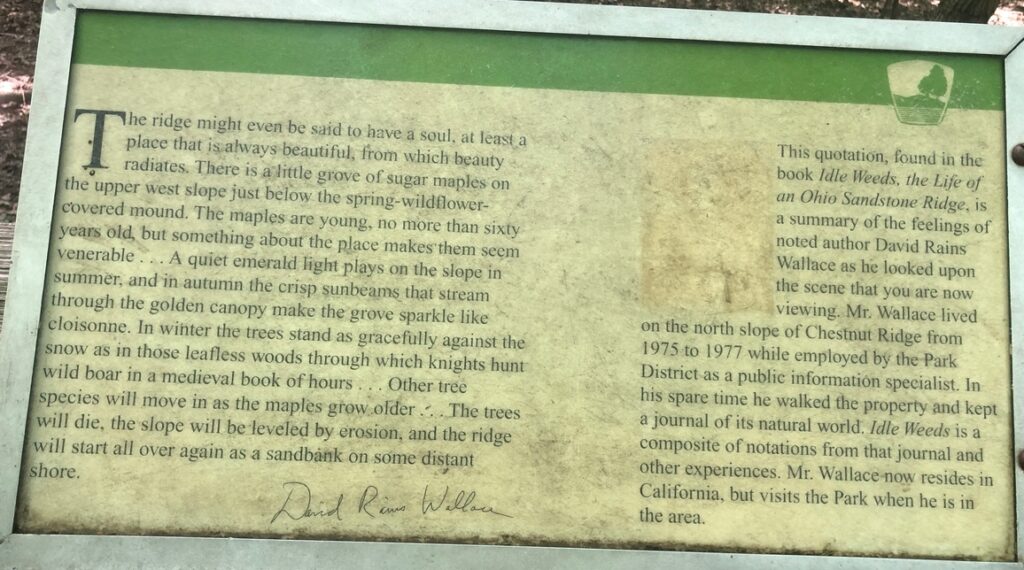

Signage

The signage at Chestnut Ridge Metro Park is unusually excellent and very suitable to supplement an encyclopedia article. So here it is.30

Meadows Trail Signs

This is the signage starting from the southern end of the trail, winding around to the northern end.

Homesite Trail Signs

These are the signs one encounters along the Homesite Trail, from east to west.

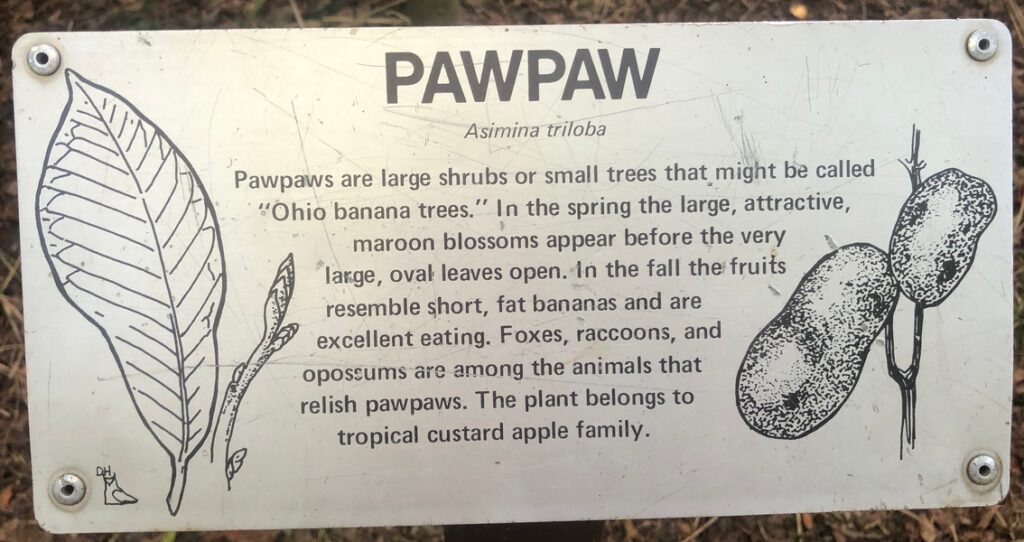

Ridge Trail Signs

This is the signage from the western side of the Ridge Trail, up to the northern branch, and then back south and east to the eastern side.

This is the first encyclopedia article in Sangerpedia, an occasional encyclopedia located at larrysanger.org, making use of the EncycloShare plugin. This plugin allows me to push this and similar articles to Encyclosphere network aggregators, such as EncycloSearch.

Footnotes

- Metro Park website, here, accessed September 20, 2023.[↩]

- Robert W. McCormick, “A Cultural History of Chestnut Ridge Metro Park,” p. 12; the report can be found in the PDF in footnote 7 below.[↩]

- McCormick’s history, ibid., p. 15, indicates that much of the land was cleared and “improved.”[↩]

- See the story of the Wagner orchard in “History,” below.[↩]

- “Chestnut Ridge: About the Trail,” accessed September 2023.[↩]

- “The Best Mountain Biking Trails in Central Ohio.” Accessed September 2023.[↩]

- This section was greatly assisted by two binders of information that park personnel kindly made available. Here is a PDF scan (97.7MB) of selected pages from these binders.[↩]

- This information is summarized from “Geology of Chestnut Ridge,” a document found in ibid.[↩]

- McCormick, ibid., p. 26.[↩][↩]

- Ibid., p. 3.[↩]

- Julie Kime, “Phase II Archaeological Survey of the Chestnut Ridge Metropolitan Park, Fairfield County, Ohio,” August 1986, submitted by Archaeological Services Consultants, Inc., Columbus, Ohio, to Metro Parks. “At the time of reconnaissance the ground cover of the project area consisted of woods and mown weeds.”[↩]

- See remarks and map in ibid., pp. 10-11.[↩]

- McCormick, ibid., p. 3. The Kime survey does not appear to opine about which people built this mound.[↩]

- McCormick, ibid., p. 9.[↩]

- Ibid., p. 13.[↩]

- Quoted in ibid., p. 16; from Hervey Scott, A Complete History of Fairfield County, Ohio (Columbus: 1877), pp. 11-12.[↩]

- Ibid., p. 15.[↩]

- John Wagner Beasley, “The Wagner Homestead—Jefferson, Ohio,” September 3, 1988, a document found in the PDF scan, linked in footnote 7, supra.[↩]

- McCormick, ibid., p. 18.[↩]

- Mike Toner, “Is this the Chestnut’s Last Stand?” National Wildlife, Oct.-Nov. 1995, pp. 25-27.[↩]

- McCormick, ibid., p. 17.[↩]

- Shea Swenson, “The Great American Chestnut Tree Revival, Modern Farmer, Dec. 20, 2021; accessed Sept. 19, 2023 here.[↩]

- Ibid., pp. 9-10.[↩]

- Ibid., pp. 10-13.[↩]

- Historical Topographic Map Collection, 1985 ed., scale 1:24000.[↩]

- McCormick, ibid., p. 18.[↩]

- Jim Fry, “Newest metro park set for opening day,” Columbus Dispatch, December 18, 1988.[↩]

- Fry, supra.[↩]

- Account “gfs69,” “Chestnut Ridge Grand Opening!” Oct. 28, 2011; link.[↩]

- All sign photos were taken September 2023. Copyright: CC-BY-SA Larry Sanger.[↩]

Leave a Reply