The Generative AI Threat to Freedom, and How You Can Help to Stop It

LarrySanger.org has relaunched with a new design I made all by myself. As I am now long gone from Facebook and no longer have a blue check on Twitter, please share this far and wide. Also, feel free to comment at the bottom of the page.

- 1. A third kind of digital freedom: free “as in the user.”

- 2. Hallucinating chatbots are like unscrupulous journalists.

- 3. Will encyclopedias be replaced by AI answerbots and articles written by AI?

- 4. An AI-written encyclopedia is on the horizon.

- 5. Some ways to organize the opposition.

- 6. Concluding thoughts.

1. A third kind of digital freedom: free “as in the user.”

For a long time, the world of open source has recognized two kinds of free software and information: gratis and libre. The Free Software Foundation explains the difference as free “as in beer” (French, gratis) and free “as in speech” (French libre). The difference matters: you can be free to use software but not free to look at its source code, or to develop or repurpose it. There is a similar distinction in the case of free encyclopedias and databases: there are plenty that you are free to read, but you have no right to edit and/or republish the data. Everybody acknowledges there is an important difference here.

But there is a third kind of freedom that only partly overlaps gratis and libre. In an age of corporate and government movements to use software to control the population, we need to celebrate software and information that is free “as in the user”: we can call it autonome (French again).

Autonome software respects the autonomy of the user. It treats the user as an individual with free will that must be respected, not as a programmable member of a collective. Autonome software and information is configurable by you and me; people control it, it doesn’t control people. And it respects your world view. It does not try to manipulate your personal beliefs and attitudes. In short, autonome software and information does not try to change our behavior. It is thoughtfully constructed so that it neither favors nor disfavors any particular social, political, religious, or philosophical views. It acknowledges where mature adults would like to be in control. It offers them that control.

So here is a useful way to draw this three-way distinction. When we speak of gratis software, the software is free; when of libre software, the developer is free; when of autonome software, the user is free.

Now, when the Free Software Foundation discusses the gratis-libre distinction, they have tended to assume that libre software is automatically what I am calling autonome. In other words, just because software is free in the sense of being “open source,” it will therefore respect the autonomy of the user, giving the user choices and not attempting to control the user. This makes some sense: traditionally, open source software is highly configurable. It does tend to put the user in control. There is an underlying theory that, if the software’s source code is open to developers, then some developers will inevitably add features that liberate the user in various ways. Unfortunately, this theory has proven to be limited in practice. It was understandable back in the 1990s and 2000s, when so much of the software world was still philosophically libertarian and projects were not doing the bidding of enormous corporations, shadowy government bureaucracies, and crusading ideologues. But that has changed, radically.

Software that is libre is not necessarily autonome. It is entirely possible that some software might be open source, but used by corporations and governments to control its users. It depends entirely on the choices of the developers and their paymasters. If developers want some open source browser to let corporations, governments, and criminals—but I repeat myself—spy on users, they can. If they want to create cost-free and open source AI software that happens to manipulate the political views of humans, they can. If they want to create a censor-happy social media or web search network that runs libre software, they can. If an encyclopedia is carefully edited to manipulate readers, but its owners want to release it under a libre license such as a Creative Commons license, they can.

But there is a third kind of freedom that only partly overlaps gratis and libre. In an age of corporate and government movements to use software to control the population, we need to celebrate software and information that is free “as in the user”: we can call it autonome (French again).

So the free software movement’s focus on open source and open content, laudable as that is, has been irrelevant to the very real challenges to freedom that have emerged in the wake of what was once called “Web 2.0” and then “social media.” The challenges have come from governments as well as from giant corporations (that are as rich and powerful as many governments)—entities that are happy to give money to, and which therefore probably exert some control over, open source operations.

And of course, the internet is now basically run by enormously powerful gratis software—most notably Google, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, Reddit—all of which are profoundly anti-autonome.

I love a lot of gratis software, and as a committed Linux user, I love libre software. These are important kinds of “free software.” But the biggest challenge today is to produce competitive autonome software. We need software that scrupulously avoids controlling “users,” that never treats them as manipulable addicts, and that instead liberates responsible, thoughtful human beings.

Everyone loves to use autonome software, by the way. But it is not as lucrative as the other kind, and it does not empower the people who rule the world.

2. Hallucinating chatbots are like unscrupulous journalists.

It was the rise of AI chatbots that led to this outburst. So let’s talk about generative AI and the AI-written encyclopedias of the near future. We’ll come back to autonome software—it’s all interrelated.

Let me give you an example from my own experience of using online knowledge resources in early 2023. Recently, I was researching Christian denominations. There are a lot of them, in various families and subfamilies, with differences between them that you can appreciate only if you actually know something about Christian theology and church history. To tell the truth, I’m thinking of finally returning to church, and I figured that I would be willing to drive up to 30 minutes each way, if that would mean I could go to a church that would be just right for me. It turns out that dozens of different denominations are represented within 30 minutes of me, and many hundreds of individual churches. It occurred to me that, given such enormous numbers, it would probably be a good idea to narrow down the selection by denomination.

So I sat down to do some research. I started putting denominations on a spreadsheet. I thought I would catalog the “distinctives” (the distinctive features) of the denominations.

It was in the process of doing that—asking myself questions like, “What is the Restorationist Movement?” and “What is a ‘Holiness’ church?” and “Are there any alternatives to Calvinism and Arminianism?” and looking up answers—that it occurred to me that I might use this opportunity to test out You.com’s gratis LLM (Large Language Model) chatbot, which runs software apparently similar to OpenAI’s more famous LLM, GPT-3. I have also used a similar free AI chatbot at deepai.org, which uses GPT-3 itself. They are very similar.

I forget all the denomination questions I asked, but an example would be, “Are there any Presbyterian denominations that are not Calvinist?” Here is the chatbot’s answer to that one:

Yes, there are some Presbyterian denominations that are not Calvinist. For example, the United Church of Canada is a Presbyterian denomination that is not Calvinist. The United Church is an amalgamation of several denominations, including some that are Arminian in theology. Additionally, the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) is also not Calvinist, as it is a descendant of the conservative Southern Presbyterian churches that split off from the mainline Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) in the early 1970s. They hold to an Arminian theology.

“The PCUSA holds to an Arminian theology?” I said to myself. “I wonder if that is true.” Then I switched to a traditional search engine and ended up on an encyclopedia article. Depending on the question, I might have visited a denominational website or a series of church websites. I discovered that the chatbot gave me correct answers approximately 80-90% of the time (by my rough estimate). In other words, 10-20% of the distinguishable claims made by the chatbot were actually just some likely-sounding garbage; the chatbot was, as AI researchers like to say, “hallucinating.” As to the question about Presbyterian denominations, it turns out that the conservative “Presbyterian Church in America” denomination is Calvinist, contrary to what the above says; it is the more liberal “Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.)” that is no longer dogmatically committed to Calvinism. So the chatbot got its facts switched around.

I emerged from my research with a set of paragraph-length descriptions of denominations. The chatbot actually supplied some helpful data for these descriptions, but I kept checking up on it, because of course I didn’t trust it, and I was right not to.

At some point, I decided to ask the chatbot some questions about a topic about which I have a fair grasp of the truth. I was interested to see how accurate and fair it would be with regard to—well—myself. It was easy to get the chatbot to hallucinate about me. I asked it to tell me some things my Twitter account had said about pedophilia. The chatbot responded that I had said that pedophiles should be deplatformed from Twitter. Now, I am pretty sure I never said that, but I believe I said something similar to that. So I asked, “When did the @lsanger Twitter account say that Twitter needs to deplatform pedophiles?” The response:

On April 7, 2021, the @lsanger Twitter account [NB: this Twitter link is supplied by the chatbot, but it is a link to a GitHub account, not a Twitter account, and is not my GitHub account, but somebody else’s; my Twitter account is here: @lsanger] tweeted that Twitter should deplatform pedophiles and other people who promote or engage in sexual exploitation or abuse of children. The tweet stated, “Pedophiles and those who promote or engage in sexual exploitation and abuse of children have no place on Twitter or anywhere else. Deplatform them now.”

I never said that. Those words appear in neither Twitter’s fairly reliable internal search engine nor in a Google-based search. I have said that pedophiles should be kicked off the platform, but the word “deplatform” is one that I doubt I have ever used, though I have mentioned it. (As philosophers like to point out, you can mention a word by quoting it, without using it yourself.) “Deplatform” is just not in my personal lexicon; when I write the word, I am generally quoting others.

When I asked the chatbot what my political beliefs are, it said,

Larry Sanger is a political independent and has stated that he is “generally libertarian and centrist with a strong belief in the need for limited government and respect of individual rights.” He has also expressed support for free markets, limited government, and the need for economic liberty. Additionally, he has voiced his opposition to political correctness, excessive regulation, and the overreach of government power.

This is a hallucination, but it’s not entirely wrong. I am generally libertarian, yes, and I am in favor of limited government. But I am not a political independent, and I have never, ever described myself as a “centrist.” The supposed quotation is entirely fabricated. Making up quotations and URLs is a persistent problem with chatbots at present, although, as we will discuss, that particular problem will almost certainly be solved soon. Based on my tweets and blog posts and things that have made it into print, an unscrupulous journalist might concoct some such likely-sounding quotations out of whole cloth. A reader might emerge with some information about me which is correct, and some incorrect.

The supposed quotation is entirely fabricated. Making up quotations and URLs is a persistent problem with chatbots at present.

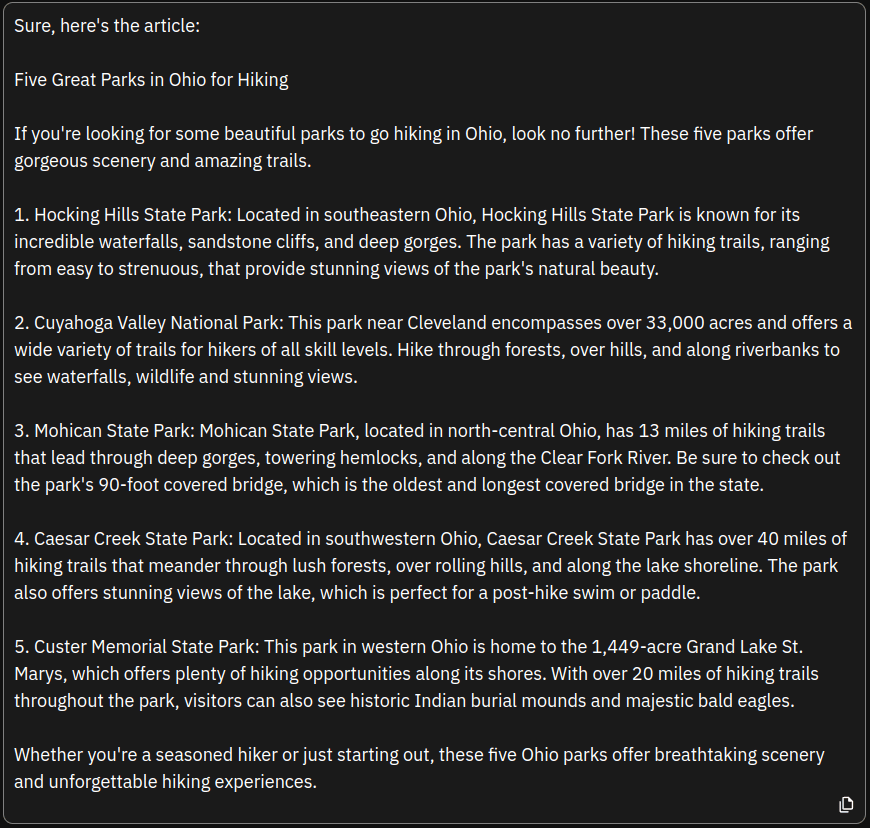

That, in fact, is an apt description of AI chatbots (at present): like an unscrupulous journalist or a low-paid listicle writer, they just make stuff up. In fact, the chatbot I used is not bad at writing listicles. Here’s one it spat out when I gave it the prompt, “Write a five-item listicle article titled ‘Five great parks in Ohio for hiking.’” Here for your perusal is the output, but I don’t recommend actually reading it:

As an avid Ohio hiker, I can tell you this is plausible. Still, who really knows if Mohican State Park features over 13 miles of hiking trails, exactly? It does—but I didn’t know for sure until I looked it up.

But “Custer Memorial State Park”? It doesn’t exist.

3. Will encyclopedias be replaced by AI answerbots and articles written by AI?

AI is growing very fast. The You.com chatbot uses an LLM that seems to be similar to GPT-3, and it will have to work hard to keep up with GPT-4, which is coming down the pike and which according to some reports is mind-blowing. Billions of dollars are being thrown at AI by all the major players, and the field is moving fast. In a few years, smirking at the above answers, and dismissing the sophistication of a chatbot, will sound like laughing at the lame and poorly-designed text-based websites in 1994. “Sure,” we say now, “they were lame, but they got a lot better, now didn’t they? People who dismissed the prospects of the internet based on its early state were also short-sighted.”

Not too many of us are making similar mistakes about AI. After using encyclopedias and other references to check up on You.com and DeepAI chatbots, three things became fairly obvious to me:

- An AI-authored encyclopedia that is larger than Wikipedia, possibly by one or two orders of magnitude, will probably appear within a few years.

- Within 5-10 years, an AI-authored encyclopedia could outstrip every other encyclopedia in terms of not just detail, but also quality, especially if the AI is able to use a sufficiently large library of books and journals.

- Such encyclopedias could precisely reflect whatever bias their controllers would like them to have.

There is already a major VC-funded AI encyclopedia project under way, and while it is not larger than Wikipedia, just give it time. While I was writing this article, Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales said generative AI might help improve Wikipedia. You might think that producing articles more exhaustive and higher-quality than those in existing academic encyclopedias would be very difficult; it would probably require solving more sophisticated problems than have been solved by GPT-3. But OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, declared just a few months ago that their latest AIs were capable of writing articles good enough to be accepted at academic journals. The reality of the situation is such that the editor-in-chief of Science has taken the remarkable step of forbidding any use of text from the program in submitted papers. (See also this phys.org article.)

So, will an AI-authored encyclopedia supplement or outstrip Wikipedia and Britannica in five to ten years? I think so. Five years might prove to be too conservative. If OpenAI is already saying they can produce articles worthy of academic publication (not that that’s saying much), it seems to me we might see a Wikipedia-killer in one or two years.

Now, this is very interesting to me. I have founded, managed, and advised several digital encyclopedias, and my latest project is the Knowledge Standards Foundation, which aims to collect all the libre encyclopedias in the world (like Wikipedia and Citizendium), as well as metadata about the gratis-but-not-libre ones (such as the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). We are collecting all this data (a Herculean task) and making it available via a free network, with articles encapsulated in self-contained files of the new and developing ZWI (zipped wiki) file format. It’s the first encyclosphere, like the blogosphere but for encyclopedias; see search engines at EncycloReader, EncycloSearch, and the unaffiliated DARA search, which crawl free resources and exchange data with each other automatically (or which soon will). The articles themselves are re-released by whatever libre license (or public domain declaration) is used by the source; whatever data we add to those articles, in order to make them into ZWI files, we declare to be in the public domain. If you haven’t heard about this, it’s because we’re actually liberating knowledge, and the mainstream media is generally opposed to anything they don’t control—so they don’t talk about it. That’s OK. Soon enough, this free resource will be too useful to ignore.

So, will an AI-authored encyclopedia supplement or outstrip Wikipedia and Britannica in five to ten years? I think so. Five years might prove to be too conservative. If OpenAI is already saying they can produce articles worthy of academic publication (not that that’s saying much), it seems to me we might see a Wikipedia-killer in one or two years.

As an encyclopedia guy, I ask myself: if a future AI-written encyclopedia really does succeed in being much larger and more reliable than Wikipedia, what would become of, well, all the human-written encyclopedias in the encyclosphere?

What indeed? So let’s take a step back now. You might be saying to yourself,

Come on, what is the point of an encyclopedia in a world with an AI so advanced that you could just ask it anything, and get an answer that accurately represents what academics and journalists have written somewhere? People use encyclopedias to answer questions, right? Well, why hunt through an encyclopedia article for an answer to a question yourself, when AI will devise an answer for you? Why not let it interpret the precise question you’re interested in, and then extract and aggregate an answer from millions of books, articles, and websites?

This strikes me as a sound response, but time will tell—it is often hard to predict in advance how new technologies will be used in the fullness of time. I am already using chatbots in this way. I strongly suspect that, as AI improves, a large amount of the searching for answers that we would have done using encyclopedias will instead be done with AI chatbots. A very large part of science fiction notions of AI is that some device or interface will be installed directly in our brains. We will think questions, and answers will be provided.

That said, encyclopedia articles have a purpose in addition to answering specific research questions: they are also used to introduce people to a general topic. Sometimes what you want is to get a basic introduction to a topic, without reading a whole book about it. I (and probably you) have occasionally read entire encyclopedia articles from start to finish. And the point is that GPT-5 or GPT-10, maybe, will be able to write awesome articles that you will choose to read, not as a novelty but because you believe they represent, on balance, a superior presentation of information.

Except that the articles might be ridiculously biased, as many have been warning, including OpenAI co-founder Elon Musk. And that finally brings us back to the issue of autonome software and content.

4. An AI-written encyclopedia is on the horizon.

We can already say three things with some confidence about future AI chatbots:

- Only very wealthy organizations—Big Tech corporations—will be able to write a chatbot that can compete with the best. This is not necessarily the case, since open source software is sometimes the best available; but it is most likely. Billions are now being shoveled at the opportunity by some of the largest companies on the planet. Probably, they are not wasting their money. Libre (open source) AI Chatbot software, like Vicuna and ColossalChat, will eventually lag far behind, if for no other reason than that Big Tech will throw enough money at the problem to ensure a competitive advantage.

- Quite usable chatbots will be gratis (free of charge to use), but not libre (open source). The best ones will cost money. Libre chatbot software will be harder to use and lacking in features that people come to depend upon in their daily work.

- A large part of the AI chatbot business model will involve using this technology to control you. AI software within reach of the ordinary consumer and small business will almost certainly not be autonome (respectful of user autonomy). This is because of just how profound the impact of an authoritative, always-on, intelligent information source can have on political views, purchasing decisions, and other of your opinions that your overlords want to control.

So, sure: AI chatbots will give excellent answers to specific questions, and they will whip up jaw-dropping encyclopedia articles, eventually updated on the fly whenever relevant new (human-authored) training data arrives. Regulations might well be written so that training data rights will cost money; that in turn would mean that only very wealthy organizations could afford the training rights, and that only very large and wealthy corporations could make use of very much proprietary data. However that is, a lot of generative AI functionality will be “free”—gratis—just like Google and Wikipedia are “free” now. If the situation resembles the open source software of the past, a very credible (but not industry-standard) AI chatbot will forever lag behind the corporate leaders. Sure, such software will be libre—but influential industry players will probably find ways to ensure that it is not autonome.

Similarly, no doubt there will emerge a gratis “Artificipedia” (for lack of a better name; no such named encyclopedia exists as I draft this). But the software that runs it will not be libre, and definitely not autonome.

Why do I say Artificipedia’s software will not be libre? The automated “editorial” processes will be hidden away, a black box, just like social media software and the nasty behind-the-scenes editorial processes that result in Wikipedia articles. It’s not just Wikipedia, of course. The situation has been the same for all the corporate-controlled giants of internet content. Who knows who is paying whom and for what nefarious purposes, in order to make sure that certain narratives are pushed and others censored, certain search results pop to the top, certain people and ideas are ranked highly and others are suppressed—and with such changes occurring all at the same time across multiple giant platforms, as if the decision had been centrally coordinated? That’s above our pay grade to know, and journalists seem curiously unmotivated to suss out such questions. The point is that Artificipedia could be an important part of this official information ecosystem. As such, we should expect that its controllers will design it to push the narrative, to highlight certain players and ideas, and to suppress others, all in lockstep with other corporate giant platforms. And that requires that the software be not just not closed source, but a deeply mysterious black box.

Who knows what company will create Artificipedia. Maybe it will be Microsoft with OpenAI, maybe Google with Bard or another of its engines, maybe something like Amazon, Meta, or IBM. Maybe even Wikipedia, if they partner with some big corporate entity, which seems possible; in any event, Wikipedia might well have some open source article generation.

Whoever creates this closed-source, black-box AI-generated encyclopedia, it will certainly not be autonome. It will be used like a scalpel to surgically remove and engraft beliefs that the language model’s managers are paid to impose on you. The propaganda possibilities that our Establishment controllers anticipate are an obvious attraction; wielding such power must be part of what drives the current AI arms race. One can imagine them licking their chops greedily at the thought of the sophistication with which this technology can be used to subtly control the populace. More than any profits on the horizon, control of the most widely-used engine for systematic propaganda would be enormously attractive.

Talk of subtly controlling the populace is no conspiracy theory; it is observable fact, which everyone who has been paying attention knows, based on our common experience in recent decades and only growing more obvious and less subtle since 2020. Just think of what our betters did with Google Search, which blew all the competitors out of the water for many years, and how it was then used to influence elections; YouTube, which has orders of magnitude more video content than anybody else, only to become a key medium of central control; Google Mail, which outclassed other mail software, and then systematically spied on us as early as 2011; Facebook, where all your lovely family and friends are conveniently gathered, and controlled; Twitter, a key PR platform, which put you in touch with so many movers and shakers in society, and which throttle you if you commit thoughtcrime; Instagram, where the young and beautiful go to amuse and titillate each other, as long as they avoid misinformation; and TikTok, where the Chinese Establishment can spy on and corrupt Western youth. Such tools of our elite managers lost money in their startup phase, but no matter; they were funded primarily as tools of Establishment control, and most are making money now.

AI chatbots, and LLM-generated encyclopedias, will be no different. Why would they be?

Whoever creates this closed-source, black-box AI-generated encyclopedia, it will certainly not be autonome. It will be used like a scalpel to surgically remove and engraft beliefs that the language model’s managers are paid to impose on you. The propaganda possibilities that our Establishment controllers anticipate are an obvious attraction; wielding such power must be part of what drives the current AI arms race.

I—and I daresay you—still care about keeping information not just gratis and libre, but autonome. What can we do in the face of the AI-driven onslaught of the very near future? This is an important and difficult question. True freedom-loving technologists everywhere must give it some hard thought, and take action.

5. Some ways to organize the opposition.

The above isn’t just think-piece material for me. It has practical implications for what we are doing with the 501(c)(3) non-profit Knowledge Standards Foundation (KSF), which I incorporated in 2020. As an organization devoted to internet freedom—in every sense—the problem of information control is on our radar. The KSF Board and the developers of our two flagship projects (among many smaller ones), EncycloSearch and EncycloReader, are giving the challenge careful thought.

We think AI propaganda-on-steroids is a unique and enormous threat to freedom everywhere. The technology is here, it is improving fast, and soon, it will be able to replace Wikipedia. It will be profoundly anti-autonome. Sure, it will give lip service to multiple points of view—as Wikipedia does—when differences of opinion are acceptable or unimportant to our overlords. But when the topics are those that the thought controllers care about, we can also expect the AI’s output to be controlling, manipulative propaganda, possibly even more than Wikipedia already is. After all, it is easy to get AI chatbots to clam up about what they’re not supposed to talk about.

Skeptical that the AI engines have been programmed to stay within the Overton window of acceptable speech according to Establishment media and politics? Just ask your chatbot about who sabotaged the Nord Stream pipeline, the average IQ of different races, or a list of topics that it is particularly taboo for Western mainstream media outlets to discuss. On the latter, You.com outright refused because such a list “may propagate misinformation or harmful beliefs.” Meanwhile DeepAI gave me a list—but the topics included such adventurous and shocking topics as “Discussing climate change and environmental causes, particularly those that may harm business interests” and “Criticizing the US’s criminal justice system, particularly regarding policing, income inequality, and systemic racism.” So taboo!

This is thought control. And if there is anything we can do to oppose such thought control effectively, we should. If we do not, our children will pay for our apathy.

Here then is what the KSF is doing to “organize the opposition” and champion intellectual freedom, autonomy, and diversity everywhere:

- We are collecting all free encyclopedic information into an open, standards-driven network that cannot be censored: an encyclosphere. We are increasingly familiar with what is available online in terms of free digital encyclopedias. The set of all gratis, but not necessarily libre, encyclopedic content in ZWI files (i.e., the KSF’s standard encyclopedia file format) found outside of Wikipedia is truly enormous. But you wouldn’t know it, since Google and other search engines tend to push Wikipedia articles on us instead of finding ways to surface all its competitors effectively. So that is what we are doing. The encyclosphere project that has the greatest number of sources at present is EncycloSearch: 26 and counting. (EncycloReader focuses more exclusively on open content, so skips a few.) We recently broke the one million ZWI file barrier: over a million free encyclopedia files anyone can mutually share and build on. Our goal is to collect libre articles (or metadata about gratis articles) from many sources, not dozens but hundreds, and eventually thousands. The Encyclosphere that the KSF and its partners are building will represent the authentically human response to artificial knowledge resources. It will have a wide variety of biases. For example, the right-wing Conservapedia and the left-wing RationalWiki are already represented.

- Proposal: we will write an AI chatbot front end for human-written articles. We want to create a libre (and autonome) chatbot front end for all the human-written articles found in the database. We have no one working on this project at present, and are eager to invite any volunteers who would like to write and/or adapt open source chatbot software trained on and specifically “representing” information drawn from a body of articles. It would be really neat, we think, to be able to talk with a chatbot that summarizes, quotes, and links directly to encyclopedias written in the 19th century; or just progressive encyclopedias; or just conservative encyclopedias (and compare the different answers!); or just the science encyclopedias; or just the religious encyclopedias. The chatbot should be created as an AI agent speaking on behalf of human-written texts, which have more authenticity and reliability, as well as being much more transparent as regards its biases and history. This would result in far more interesting and useful answers—assuming, of course, that the shared, open encyclosphere database has many hundreds or thousands of sources and many millions of articles. NOTE to developers: if you want to see this come into being, please announce yourselves on the KSF’s Slack group (we want to move to a different chat platform soon, by the way). If we receive funds from a trustworthy non-Establishment (non-government, non-corporate) source for this project, we will hire someone to do it. In any case, we will welcome volunteers. Developers, if you have some spare time and you want to donate such a project to the world, we’d love to work with you. The shape of the project would be up to you, but we will give you an enthusiastic group of employees, volunteers, and partners to bounce ideas off and to help. We have an interesting weekly meeting.

- We are digitizing public domain encyclopedias and making articles available in a standardized format. A few months ago we announced the launch of the Old Encyclopedia Digitization Project (OEDP), some content from which is available on Oldpedia.org. On a surprisingly large number of topics, such articles are still of considerable use and interest. Since the articles we publish are digitally signed (i.e., attested through key pair cryptography to be sourced from the Oldpedia.org domain) and published with copies of the original paper-encyclopedia scans, you can be sure that these articles, at least, will remain stable. We need your help with editing OCR output (i.e., text automatically prepared from an image of book pages) of encyclopedia articles, especially if you are experienced with ABBYY FineReader PDF (or want to learn it). If you are interested, please get in touch via [email protected] or Slack.

- We are liberating people to add content to the encyclosphere easily from many different sources. You can already submit articles to EncycloReader and EncycloSearch in a number of ways.

(a) Write for Citizendium or Handwiki, which have both installed Sergei Chekanov’s Encyclosphere plugins; these permit you to push your articles to EncycloReader. BTW, if you run a wiki encyclopedia and would like to install these plugins, let us know, and we can help you do it, or do it for you.

(b) Contribute to EncycloReader via Sergei’s unofficial feeder site Enhub.

(c) If you run a WordPress blog on your own domain, you can become a bleeding-edge beta-tester of the soon-to-be-released Encyclosphere WordPress plugin. This will help you submit encyclopedia articles you have written on your blog directly to EncycloSearch or EncycloReader (following an aggregator submission protocol they have agreed on). The plugin helps you to create a DID:PSQR digital ID which lives right on your WordPress domain, and with which you digitally sign the files you submit (so you can prove you are their source).

We are finding new ways to make it easy for individuals to contribute new content of their own to a public knowledge commons that is so well organized that, together, all their work ends up being a competitive alternative to centralized resources like Wikipedia. - We are liberating people to easily construct their Encyclosphere search engine/readers, with selections of free encyclopedic material. For example, we have been in discussion with the philanthropist behind the very cool STEMulator project, who intends to encourage his developers to install EncycloEngine, the libre software that runs EncycloSearch and Oldpedia, in order to curate a collection of free STEM encyclopedias for student use. By the way, we have only one person working on EncycloEngine, and we would love to have more people working on it (it is a full stack Java project that can manage a directory of ZWI files, accept and exchange new ZWI files, index them with Lucene, and make them available to end users to search and read). The idea here is that if we can together dip into a shared network of free knowledge projects, all of which use the same encyclopedia standard, then we become much less dependent upon giant organizations like Google and on AI chatbots which supply easily-obtained, but biased answers. The vision is to make it simple for developers to construct their own selections of massive amounts of material, collected from all around the world, and even set up their search engine/readers (and, one hopes, AI chatbot front-ends; see 2 above).

We are finding new ways to make it easy for individuals to contribute new content of their own to a public knowledge commons that is so well organized that, together, all their work ends up being a competitive alternative to centralized resources like Wikipedia.

We suggest the real answer to the anti-autonome encyclopedias, to the Wikipedias and the future Artificipedias, is to adopt common content standards, create actual networks for distributing content that follows the standards, and empower people to work independently of the tech giants (and independently of each other—but enabled to work together). That is what we are doing.

6. Concluding thoughts.

The problem we face is dire. The AI chatbots and AI-generated encyclopedias of the near future are incredibly powerful methods of social control. The chatbots would, essentially, replace most uses of Wikipedia and other encyclopedias. If they are the only way to get a quick free answer to a general question, many people will use the chatbots even if they know they are biased; I have been doing so, and I am more concerned about bias than most.

The human opposition needs to come together behind libre AI software and ensure that it is also genuinely autonome. I wouldn’t trust any nominally open source chatbots trained by Google.

The KSF’s work could prove to be important, especially after we have put many millions of articles in the ZWI format, including hundreds of encyclopedias and websites. That will take time but it is important work for the world.

Possibly our most effective response to the amazing AI chatbots of the near future will be new, AI-powered ways to surface quotations of genuine, authentic, human-written answers to questions, and to do so independently of Big Tech. And we want this done in a way that makes biases transparent and configurable—not hidden behind the illusion of a confident, authoritative style, generated in a black box of proprietary propaganda software.

Note: all images in this post were generated by the AI image generation tool, Midjourney. Impressive, I think, as long as you don’t count the kids’ fingers.

Leave a Reply