If God exists, he knows all the physical explanations of all the phenomena. From his point of view, there is no “God of the gaps.”

Hence our inability to explain something about the world is no reason to infer that God makes human-style arbitrary choices. In other words, for example, God’s mechanism for creating life would be evolution, of course. Where there are inexplicable-seeming leaps, surely God would know of the explanation. But our ignorance is no argument for theism in itself, of course, any more than any scientific fillings-in of erstwhile gaps in our knowledge is an argument for atheism or scientific materialism.

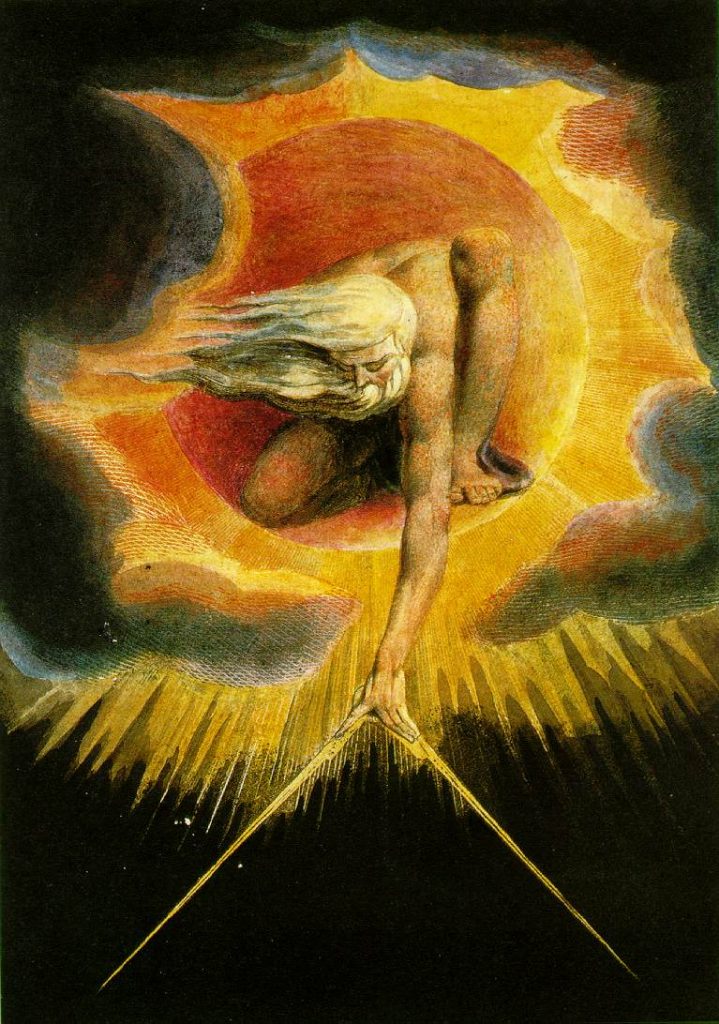

Even if we had a perfect scientific explanation of everything from the Big Bang, to the universal constants, to the origin of life, to every last evolutionary gap, one might still feel impelled to the conclusion that the explanations themselves seem to be guided by purposes. It is not the random-seeming things in the universe that might reveal divinity, but the awe-inspiringly ordered and comprehensible things.

It is not the random-seeming things in the universe that might reveal divinity, but the awe-inspiringly ordered and comprehensible things.

If we could not state what these purposes were, then this would seem to be mere superstition. But scientists become theists because God’s purposes seem clear: the universal constants permit the existence of spacetime and the coalescence of matter, and in particular stars and planets; certain unlikely chemical facts (we don’t understand them all) are absolutely necessary in order for life to exist; certain incredible evolutionary leaps seem designed to lead life on earth ever onward to greater awareness and knowledge, culminating in man.

It is not the gaps in explanation that would lead one to infer God from the cosmos, if one were inclined to make that inference. It is the fact that the insanely particular natural laws and constants we have discovered indeed have resulted in such a splendid cosmos.

It seems indeed so splendid that the specific laws and constants that explain it all appear to reveal a mind with purposes. That, surely, is the thought that has driven so many people to accept the design argument—not that divine intervention is necessary to fill in the current gaps in our explanations.

Reply to “On the “God of the Gaps””