My conversion story weighs in at 14,000 words, and this follow-up is another 5,000. The outpouring of response has been so great that I felt I owed some further answers to all these lovely well-wishers, who are, after all, now my brothers and sisters in the family of God.

Since I posted the essay, less than three weeks ago, there have been over 250 replies (still coming in), and that is only directly on the essay itself. There have been multiple popular threads on Twitter, in effect launched by Megan Basham, everyone welcoming the new brother to the family—and who knows how many on Facebook and other social networks. There have been a bunch of YouTube videos, each filled with well-wishers. I was asked to do a lot of interviews, include ones by Sean McDowell and Allie Beth Stuckey; still more are in the pipeline. There were news stories from The Gospel Coalition, World, CBN, Christian Post, Relevant Magazine, the Discovery Institute, and quite a few others (including many in foreign languages; see the links among the replies to the essay, including some very interesting blog responses, most interestingly by Bethel McGrew. Maybe the most unexpected thing is that at least two preachers mentioned my conversion in their sermons and blogs.

I’ve been frequently asked: Was I surprised at the response?

No—that’s not strong enough. I was nonplussed, shocked, in profound consternation for days. I was not planning on spending February dealing with the aftermath.

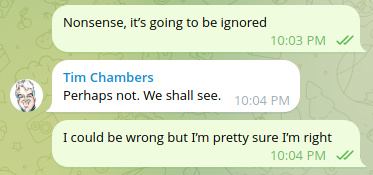

I had told a friend who read an earlier version, on January 27, “It’s going to be ignored.” He answered, “Perhaps not. We shall see.” To which I responded, “I could be wrong but I’m pretty sure I’m right.” I thought so because the essay is very long, self-indulgent, and kind of geeky and philosophy-heavy. I thought only geeks would like it. But even my elderly mother liked it. (I am still tech support to her.) She told me that her prayers of many years had been answered.

For a while I just couldn’t understand why so many people would be interested. But people have explained, over and over: my story is familiar to them in many points, despite its quirks. Many told me (and everyone else) their stories, which were evidently heart-felt and quite varied. Over and over, some respondents told me that they too had wrestled with well-meaning skeptical doubts and basically gave up on Jesus, the Church, the Bible—the Christian faith—for years on end. And then they came back. In some cases, they joined the Lord’s family for the first time, despite life-long atheism. So many people said they appreciated what I thought would be, to them, boring little details.

They told me repeatedly that my story gave them great encouragement, so that they sent it to doubting friends and family members—for which I thank God. Will my work really help reconcile some of my fellow sinners with their loving creator? How wonderful. I suppose I hoped that, but I didn’t expect it. Sola Deo gloria. I guess the notion is that my story is effective as an explanation of how someone might come, through relatively “intellectual” means, to the faith. Well, I suppose it is that. I am just overjoyed to learn that this approach resonates as much as it apparently does today. Because, in that case, maybe I really can be of some use.

Anyway, I have not had time to answer to all the responses, certainly not individually. But I do owe at least a collective answer. I will begin with the topic most often commented on: my failure to attend church.

Post-conversion church-going

Many people read the section titled “Church?” carefully, and I feel I was unusually well understood by them. That in fact is something I feel enormously grateful and blessed by in this response: so many people now understood and sympathized with me on something that formerly was rather private and hidden from view. But, although the section did explain my reasons for not attending church (for now), it left some important things out.

I attended church a half-dozen times in 2020-22, at three different churches not very far from me. (I thought it was four, but I can’t locate the fourth.) Two were through-the-Bible teaching churches, and one was denominational. I enjoyed all the services, although my profound hearing loss posed difficulties catching everything that was said. In all three cases, the congregations were lovely, welcoming, but elderly. Though I was in my 50s, I was decidedly on the younger side. I found myself missing the traditional hymn-singing of my youth, with too much focus on newer songs. I also discovered that, although I liked close attention to Scripture, I was not that interested in mere exegesis. I actually did want more topical sermons. I mean explorations of doctrine centered around topics, focusing indeed on relevant Bible passages, but also inspiring the congregation to ever-greater sanctification. I had quite enough of Bible study throughout the week. For homilies, I greatly enjoy those of a certain Orthodox priest whose videos are constantly interspersed by “we must…we must…”. I find myself responding: yes, we must indeed. From a spiritual leader, I, at least, need moral inspiration. I just didn’t want it to be political, as it was in some cases, nor lightweight and driven by long personal anecdotes, as is very typical for most topical preaching. I have viewed many hours of local preachers, and these problems, more than any others are what keep me from attending.

But since 2023, I haven’t been to church. I explained in my essay why I decided to stay away. But I wasn’t clear enough about something. One of the biggest problems was, and is, not just that I might offend the pastor or congregation by moving churches; yes, that’s a concern, but I’m sure they’re used to that. Nor is the problem that I first want to be “doctrinally correct,” for no special reason. Rather, the problem is this. I worry that it would become news that I was attending a church of a certain denomination. What if people got excited about a long-time unbelieving co-founder of Wikipedia joining their denomination and church? I wish that wouldn’t matter, but I think it might. In that case, it could prove to be disheartening to them if I then left the denomination and proceeded to explain my theological reasons online. That could be deeply alienating, I think, to those who care about their doctrinal distinctives. I know I’m not that important, of course, but I would regret terribly if my departure undermined the pastor, even causing others to leave. I refuse to do that. As a student of the Bible and of theology, I want to support the men of God and the strength of the Church wholeheartedly. Before my essay came out, I saw some evidence that this might become an issue. And now, I suppose it would be even worse, because my story has been splashed across Christian news outlets for over a week. Do you see what I mean here?

In short, I have been writing and making videos about various theological issues. What if I end up publicly contradicting my new denominational home, when I could avoid that simply by prioritizing the questions that divide the denominations? I can’t guarantee that I would never change my mind, but at least I would avoid frivolous and early departures. When I have the time, between my day job and Bible study, I will prioritize answering the aforementioned divisive questions. Hopefully I will be able to narrow down the list (see the next section), confident that any future changes at least will not be frivolous and easily avoided.

In the meantime, I am conversing in very edifying ways on a daily basis with my now-active Bible study group. We have had to close it to new members—we got so many joiners, and I just don’t want to overwhelm the people already there. I know this is no substitute for church, but it’s part of the universal Church. So I hope it’ll do for a little longer, anyway. I’ll “get me to the church on time,” I reckon.

Denominations

Some respondents detected denominational tendencies in my essay, suggesting everything from Reformed Presbyterianism and Lutheranism to Catholicism and Orthodoxy. Others, not presuming to read my mind, nevertheless tried to press me into their denominations. I certainly appreciate the well-meaning advice here. But I can’t please everybody, that’s for sure.

Let me explain briefly, then, some (not all) of the things I like and dislike about various denominations. I don’t mean to alienate anyone or take sides as a partisan. I want my testimony to be a tool suitable for all denominations. So, in what follows, I am just explaining myself, since people talked so much about church-choosing. Maybe this will help people give me more focused advice.

I will not bore you with all my thoughts on denominations. I am being selective. But I worry that you will think the following is “reductive,” i.e., reducing complex traditions to a short list of items. These are merely illustrative high points and not at all complete analyses. Trust me, I know there is quite a bit more to say than I am sharing here.

First, I am sorry to disappoint my Catholic friends, but the chances of my ever becoming a follower of the Roman Catholic rite are vanishingly small. I disagree about the foundational matters of sola scriptura and sola fide (blog post forthcoming), to say nothing of the other solas. Its rigid and contrived defense of its doctrine by strained interpretations of Scripture and the early Church Fathers is frankly a source of irritation to me. Moreover, I think the Roman Magisterium, even on the rare occasions when it speaks ex cathedra, has been wrong about many things, such as the Immaculate Conception of Mary; hence, it does not speak infallibly when it claims to be doing so. I do not mean these remarks as a personal slight, but only an explanation of my position. (I don’t hate Mary! Honest!)

I find myself rather closer to conservative Orthodoxy, and I have enjoyed every minute interacting with and watching videos of Orthodox believers, including a priest I would count a friend. I admire the evidently deep commitment of Orthodox believers to holiness, and their warmth. What you read about in Dostoyevsky still seems to be found within this part of the Church. That said, having absorbed a careful and interesting book about how Orthodoxy is rooted in the “religion of the Apostles” and the first-century Church, I find myself decidedly unpersuaded that it is permitted to us, for example, to attempt to pray to dead saints; I know Orthodox believers deny that this is what Saul tried to do with Samuel, but I’m not sure I agree with them. I would have a hard time giving up sola scriptura, as Orthodoxy would expect me to. I might eventually come to differences over sola fide as well, but here I am less sure, due to the widespread confusion over the meaning of “faith” and Orthodoxy’s interesting understanding of what they call synergeia, or cooperation with grace.

Conservative Anglicanism (not terribly large in the U.S., but no matter) also seems like a strong possibility. As a relatively large-tent denomination, this might be a good home for me. I have learned quite a bit from Anglicans, maybe next most after Calvinists, but here I would be nervous about the influence of “Anglo-Catholicism,” including such things as praying to saints and undue adoration of Mary, as well as ongoing liberalization of the denomination, even within some dioceses of the ACNA.

I actually do rather like conservative Presbyterianism, except for the very thing that is perhaps most distinctive about it: the deterministic Calvinism stuff. I have no issues about signing onto a broadly correct confession, and I find I like what I know of the Westminster Confession quite a lot. Except TULIP—I’m pretty sure I disagree with every point in TULIP. Sorry, but I am not seeing these doctrines reflected in Scripture, and I see quite a bit of Scripture in considerable tension with them. I’ve also watched a lot of Leighton Flowers; what can I say? But I have not yet really carefully studied these issues. Could I change my mind? Conceivably. As a philosopher, though, I have relatively well-developed views about free will, and I’ve noticed an abundance of data in the Bible pointing to the essential importance of free will in theology. This is something arch-Calvinist John Frame himself more or less admits regarding compatibilist free will in his Systematic Theology.

Ditto, conservative Lutheranism: I like it quite a bit, except for the thing that is maybe the most distinctive thing about it among American Protestants, namely, sacramentalism. (This is the view that baptism and communion are “means of grace,” and required, for most believers, for salvation.) I would like to think that quibbles on this issue do not matter that much, as I said earlier; but I am apprised that Lutherans would disagree that they are quibbles. I know that they distinguish their view from Catholic sacramentalism, rejecting the idea of ex opere operato (grace imparted by the act alone). I do think the ordinances of baptism and communion can be nearly as strong as you like, even if I am breaking one of these, in that case, for now. But I am not convinced that they are required for salvation, according to Scripture. This is highly debatable; there are strong “proof texts” on both sides. (Have fun comparing John 3:5, Mark 16:16, and Acts 2:38 with Luke 23:43, Ephesians 2:8-9, and 1 Corinthians 1:17.) I’m also chary about the “real presence” of the body and blood of Christ in the Lord’s Supper; I am inclined to think of these as deeply important symbols we use to remember his sacrifice for us.

I have some good associations with conservative Baptists. I am only slightly inclined toward believers’ baptism at this point, but the strong presence of “Free Will” Baptists in the overall movement and the stand on the “ordinance” view of baptism and communion seem to be decided points in their favor, for me now. But some Baptists, like it or not, have the reputation of being hostile to deep, probing questioning. Now, I know this does not apply to people at Baptist seminaries, many Baptist pastors, and some congregations. But some of the Baptist people in the pews wouldn’t take kindly to a character like me piping up too much; I’m not sure I’d be a good cultural fit in some Baptist congregations. But I am told the Baptist movement is very broad and deep. One other problem is the historical and, to a certain extent, continuing prevalence of dispensationalism. For now, insofar as I understand it, I take the classic and historical view that the Church will fulfill the promises made to Israel, which will indeed be fulfilled. The Gentiles have been grafted into the single tree, and we Christians are all, whether Gentile or Jew, subjects of the true Israel, which is one and the same as the Kingdom of God. Some Baptists broadly agree with this, yet Baptists still make up the single biggest denominational home of Christian Zionism, which seems opposed to this credo. This could present a challenge, but not at all Baptist congregations, which do vary.

The last really big denominational family is, broadly speaking, Methodist, and started by John Wesley. In the 19th century, the Wesleyan/Holiness movement branched off. Of this family, the largest branches are still called “Methodist.” While most of Methodism is quite liberal today, the broader family has conservative denominations in the form of the Wesleyan Church and the Church of the Nazarene, as well as the newly-launched Global Methodist Church. Methodism is ultimately an offshoot of Anglicanism and prioritizes sanctification much more than other Protestant movements—and in this regard, resembles Orthodoxy. My understanding is that conservatives have been fighting a losing battle against liberalizing tendencies within the branches started by Wesley for over a hundred years (though, in the beginning, it was quite orthodox in its doctrine). This apparently remains an issue even within the conservative branches as well, but again, there are exceptions, of course.

Other movements and smaller denominations have their own issues, in my eyes, at this point. I’ve considered Calvary Chapel, which seems about right on Calvinism vs. Arminianism, and on other issues; but the Baptist sort of tendency toward dispensationalism and some related views might ultimately put me at odds. The Church of Christ has an admirable program of wanting to return to the vision and standards of the very early Christian church. They also have a list of five things needed for salvation, which seems contrary to sola scriptura. I honestly never gave Pentecostal or charismatic denominations much consideration since I am neither a terribly emotional sort of person nor do I find a lot of convincing evidence of continuationism (but again, I am not very sure on this point). The Evangelical Free Church (with Scandinavian roots) seems like a good fit—it is explicitly “big-tent”—except that it has been reportedly moving in a decidedly liberal direction. As an Ohioan, I have a soft spot in my heart for the kindly and morally ambitious Mennonites. But I wonder about their commitment to hard theology; and I’m not about to give up technology; and believe it or not, there is a strong liberal and modernizing tendency in about half of this movement as well (perhaps an overreaction to their historical roots).

Again, this is not meant to be reductive; I remain sensitive to nuance, and torn.

My study program

(Skippable. You have been warned!)

Many people have recommended a wide variety of books, for which I am grateful. I am always looking for things to add to my list, or reasons to revise the priorities in my list. So, in case anyone really wanted to help in that regard, I thought I would share my study program, with the broad topics introduced in bold. Most of the following section is a wonkish sort of annotated bibliography.

Rather than discuss individual recommendations, I will describe my curriculum so far. I actually wrote about the very idea of theological self-study on, as it turns out, the last day of 2020, the year of my conversion. My aim was to study the sorts of things one learns in an M.Div. program, but on my own, at my own pace.

I wish I had more time to study, but there are only so many hours in a day, even if my days are busy. I tend to gravitate toward the classic, fundamental, and most influential—and the conservative or orthodox.

In 2022, I began taking long walks during which I “talked with God.” On the trip to and from these walks, and whenever else I am out driving by myself, I nearly always listen to theology. I use the Apple Siri “read text on page” when there is no audiobook available; it’s imperfect, but it works. It turns out that you can go through a lot of theology this way, if you do it day in, day out, for around five years. And maybe I take extra-long trips through the pretty Ohio countryside.

I almost never use these driving trips to do my daily Bible reading—that’s too important. I’m now wrapping up a fifth Bible reading. Beginning with the second time, I have almost always read the assignment twice per day, which has allowed me to get quite familiar with several different translations, including KJV, NKJV, NASB, and NIV, among others (including much of the “Easy-to-Read Version” when I went through the whole thing with my sons, as I did). I have always consulted secondary sources. The last two years I have gone through about 90% of the notes of the ESV Study Bible (this is hard work). In the past, I have used a variety of other commentaries, either on the Life Bible app or using BibleHub.com (or its identical app); my favorites there include, especially, Gill and Ellicott. Yes, these are all conservative and many older sources—you know, people who actually believe the Bible.

I have also studied some of what is called Bible introduction. Beginning in 2020 and repeated once or twice more after that, I went through basically all of the Bible Project videos. These I can recommend, and although the authors are a little unorthodox in some of their theology, they take efforts to be acceptable to a wide range of theological views. By this April, I will have gone through the entire, deeply inspirational David Pawson lecture series, Unlocking the Bible; I started listening to selected Pawson lectures in 2020, too. In more advanced introduction, I listened to Gundry’s Survey of the New Testament lectures. Then I tried to get into Carson and Moo’s very advanced Introduction to the New Testament, but decided it was above my level (at the time?), and opted for Tenney’s New Testament Survey. I will be finished with Daniel B. Wallace’s free, online, and academic New Testament: Introductions and Outlines this April. When it comes to Old Testament introduction, I have been much less diligent. My main exposure has been from the Bible Project and Pawson and reading brief introductions in Bibles. I started but need to finish Archer’s excellent Survey of Old Testament Introduction. I’ll be filling in this gap in this year, though.

As to commentaries, I have never gone through an entire commentary except on Genesis, on which I read all of Matthew Henry, The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, The Bible Knowledge Commentary, and Josephus. I also read Swindoll’s studies of Abraham and Joseph. This was all part of a special study of Genesis. On an adviser’s recommendation, I also dove into related Biblical texts and archaeology, reading the relevant parts of Arnold and Beyer’s Readings from the Ancient Near East, Matthews and Benjamin’s Old Testament Parallels: Laws and Stories from the Ancient Near East, Kennedy’s Unearthing the Bible: 101 Archaeological Discoveries, and Provan et al.‘s Biblical History of Israel.

I wrote a lot of questions and answers about Genesis, and for each chapter consulted the corresponding commentaries, and sometimes others as well. This was my first exposure to really in-depth exegesis. I also gave the same treatment to Matthew 1-3, using the same resources (except Josephus, of course; but now adding ChatGPT’s feedback on my answers, and Ryle’s whole introductory Expository Thoughts on Matthew). All this exegetical work, which is extremely interesting to me, tapered off and ended because my answers were getting too long and I just had less and less time to spend.

In systematic theology, I’ve read all of Frame’s History of Western Philosophy and Theology, which is a bit misnamed as it views philosophy through a theological lens. It was interesting to see how a theologian treats philosophy. Then I went through the same author’s Systematic Theology, complete. It took a long time; it was worth it. It confirmed that I like Reformed theology, generally speaking, except, ironically, for the TULIP part (which is essential to Reformed Calvinism). I also read many chapters of Grudem’s Systematic Theology. I am now about two-thirds of the way through Allison’s excellent Historical Theology. Next time around, I will, of course, turn to another theological tradition.

In specialized theological topics, I read de Young’s Religion of the Apostles: Orthodox Christianity in the First Century; the McNall lecture series, The Mosaic of Atonement; and I would put Packer’s modern classic Knowing God here. Maybe some others. Early on (2021?), I read Montgomery’s The Theologian’s Craft, but doubt I properly appreciated it at the time; it is short so I must re-read it.

As to church history, I went through Shaw’s Christianity: The Biography: 2000 Years of Global History. I’m pretty sure I went through a lecture course at The Great Courses. I also read a fair few classics, including the Apostolic Fathers (twice), Eusebius’ Church History, Augustine’s Confessions, and bits and pieces of other ante-Nicene Fathers and the Ecumenical Councils. I am now listening through the City of God.

Another strong interest of mine is apologetics, philosophy of religion, and philosophical theology. I began by listening to Lewis’ classic Mere Christianity again. I say I listened to Lewis “again”: it seems I first bought and listened to it in 2011, but obviously it didn’t take. Then came Strobel’s The Case for Christ twice; it was so good. I read Anthony Flew’s There Is a God: How the World’s Most Notorious Atheist Changed His Mind. This was interesting but ultimately disappointing, since he died a mere deist. I reminded myself of the content of a philosophy of religion course by listening through the solid Great Courses lectures by James Hall; it was all quite familiar, like riding a bicycle, but still useful. I got some basic introduction to the theology of miracles from books by Lewis and Metaxas, but need to do something more serious reading there. I wanted an intro to the debate over “creationism” and “intelligent design,” so I ended up reading Dembski’s Understanding Intelligent Design and then Behe’s Darwin’s Black Box, as well as half of Dawkins’ The Blind Watchmaker. I was surprised both at how plausible Dembski and Behe were, and at Dawkins’ utter failure to engage with their sorts of arguments. The latter in particular was a little weird to discover. I read Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, because I had never done that before. Later, I—”heroically”, I suppose, that’s what it felt like—attempted to listen to Craig and Moreland’s mammoth and advanced Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology. I got almost halfway through but had to stop and put it off until I had time to slow down and read the words on the page; just listening, I couldn’t keep up with all the symbols and abbreviations. Then I picked up Craig’s Reasonable Faith, which was much more tractable for listening. I also read Davis’ excellent Introduction to Christian Philosophical Theology, a chapter of which inspired this essay.

A basic feature of any M.Div. program is hermeneutics, the theory of biblical interpretation. I found this extremely interesting. I started with Sproul’s Knowing Scripture, which is a good place to start, indeed. I then did Klein et al.‘s lecture series, Introduction to Biblical Interpretation. After that, on advice, I struggled through Carson’s Exegetical Fallacies, and most recently read Chou’s remarkably good Hermeneutics of the Bible Writers. This really opened my eyes to the beauties of intertextuality, something that anybody who has looked at enough Bible cross-references has noticed, but rarely with such consistent and inspiring profundity.

I have read parts of other works, and consulted reference works I won’t mention; I’m mostly just listing the ones I finished. I have also read 5 or 10 Christian novels. I love Pilgrim’s Progress, which I have read three times, and Dostoyevky’s Brothers Karamazov, among others.

As to my book in progress, I will add only that it is a steady discipline of mine now. I have done a little other background reading for the book, but mostly, the writing is informed by the above study and the knowledge I had gleaned before that. It is obvious to me that I need to do more focused background reading and library research before publishing the book. I appreciate all the encouragement I have received about the book, but I will not publish it until it’s in the shape I want it to be in.

As you can see, I’ve been busy reading many things, so I’m always happy to get more book and author recommendations. My self-assigned task thus far has been simply getting up to speed on basic Bible interpretation, theology, and exegetical skills. I won’t be stopping anytime soon.

Has my conversion been merely intellectual?

Another concern, always kindly expressed, is that, after all my cogitation and study, perhaps I still have no faith. Perhaps, some people suggested, I need to spend more time on more purely spiritual matters. I want to reassure these people.

First, I should admit, and I know this is important to many regular church-goers, that I have been missing all the spiritual benefits of attending church. I have mostly avoided not just face-to-face fellowship, but also corporate worship and singing; and I know the sacramentalists (and others, too) would say I am missing something deeply essential by not partaking of the Lord’s Supper. I hope this will change sooner rather than later.

This, however, is not the main thing that respondents were concerned about. They were especially worried that I might not have a keen faith, or even that, perhaps, I did not truly accept Jesus as my Lord and Savior. But let me assure you that I truly do. Let me illustrate.

One of my disciplines is to attempt to pray seven times per day. The first, as I get ready for the day, is always the Lord’s Prayer. I often forget to do all seven prayers; maybe someone has an idea of how to maintain this discipline more consistently. But Paul wrote that we should “pray without ceasing,” and this is how I do my best to follow this injunction. I attempt to imagine what the Lord might say to me, in my daily circumstances, and I try to remember what the Bible says on related issues.

I cannot adequately express how useful it is to be increasingly familiar with the Bible for this purpose. The more we read, understand, and apply the Bible, the more vivid our notion of the character of God becomes. Those non-believers who maintain that the God of the Old Testament is some sort of brutal tyrant are merely revealing their own ignorance. If they made a better attempt to read and understand the text as its recipients understood it, they could not maintain their attitude. The better I know God, the better I understand why he is truly called sovereign, merciful, and loving.

The point is that in “my Christian walk,” as the phrase has it, I am intensely aware of God in my life. I regularly thank and praise him; I confess sins and repent of them; and I ask things of him for myself and for others. I also listen—having absorbed what I have of Scripture—for his answers. What it means to be Christian, perhaps most essentially, is to accept in a deep way that he is our Lord and Master. I certainly do accept that. In fact, despite my long history of methodological skepticism, I have not seriously doubted it since my conversion. For me, this is never a matter of mere intellectual assent; it is, rather, firm loyalty to Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

Leave a Reply