You have probably heard about how it is obvious that there can be a lovely old man, but not an old lovely man; or an enormous French cheese, but not a French enormous cheese; or an oval running track, but not a running oval track; etc.

In English (other languages differ), we seem to have a prescribed order in which the adjectives are prepended, something like this:

- Opinion

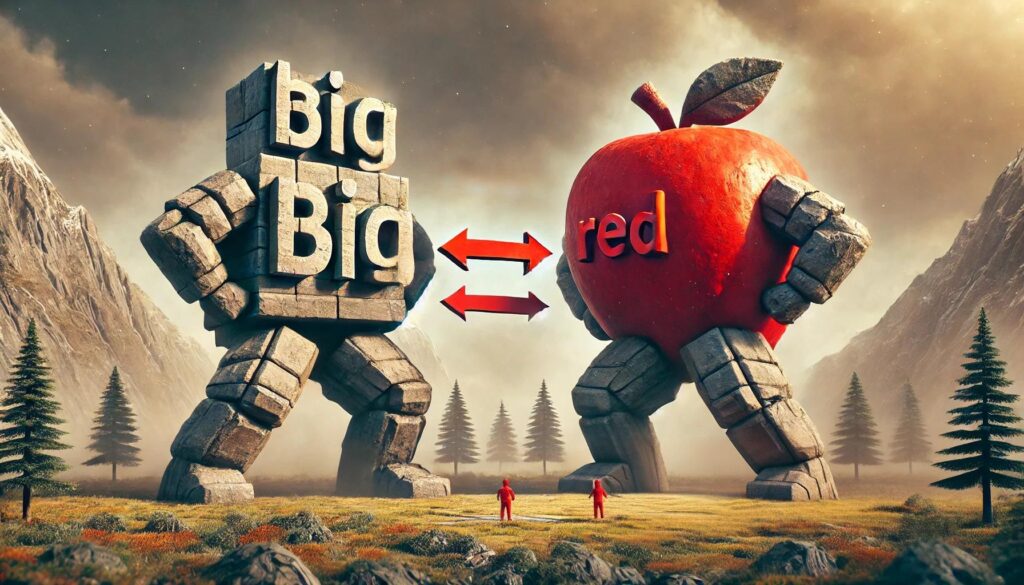

- Size

- Age

- Shape

- Color

- Origin

- Material

- Purpose

It seems to me we could not learn such things automatically if there were not some simpler, more intuitive description of the rule, just as there are always simpler, more intuitive descriptions of complicated rules about endings governed by gender, number, and case.

Well, when it comes to the order of adjectives, it seems to me rather obvious that the adjectives go in order of least to most essential (in English). It’s a “lovely old man,” because a man’s age is understood by all to be closer to his identity than his loveliness, especially insofar as his loveliness is a matter of opinion. A cheese can have many qualities, but its origin (like France) is regarded as much more essential than the size of the cheese. And of course, the purpose of a track is far more essential than its shape; a running track is just a different thing from a slot car track.

I have a sneaking suspicion that one reason this is (a) not obvious to everybody and (b) not a common grammatical theory is not that it is incorrect, nor that it is unobvious, but that it trades on a commonsense notion of importance or essentialness. And if there is one philosophical idea that modern academics of the English major type hate, hate, hate it is the idea of essences, or essentiality. Just ask them, they’ll tell you all about it. These are the people—originally, feminists—who started saying that there is nothing essential about being a woman, or a man, and thereby started gender theory. That’s essentialism! Boo, hiss!

But the fact of the matter is that we really do know quite intuitively and universally what is more or less essential. We daily press our commonsense notions of essentiality into service.

Perhaps there are some grammar American white young large silly specialists out there who would care to disagree?

I mean, I admit I could be wrong. My hypothesis does seem testable.

Leave a Reply