This post was updated Sept. 18, 2024, after the launch of the ZWIBook flash drives.

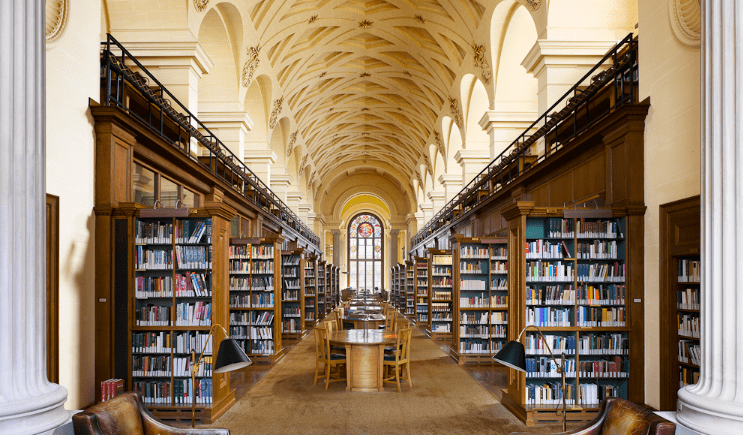

It used to be that a visit to the library was something to celebrate. One wandered the stacks, picking up fascinating volumes at random, discovering whole fields and respected authors one had never heard of. The knowledge was right there, between the covers of books, many books in a row all on the same subject.

No longer. Public libraries have become deeply depressing places.

Now, I have occasionally visited the Ohio State University library. It hasn’t changed much, and the experience I described can still be had there. In fact, it has grown, and while many of the stacks have moved off campus to a special facility, a massive selection remains for browsing.

But at the once-enormous Columbus Metropolitan Library, regarded as one of the best less than twenty years ago according to the Hennen’s American Public Library Rating, everything has changed.

I had to visit the main library because I needed access to the Foundation Directory (for fundraising for the Knowledge Standards Foundation). Access was available only on the premises. When I arrived, I was greeted, well, strangely: two or three librarians stood next to modern check-out desks, looking (could it have just been my imagination?) hungrily at the visitors, eager to have someone to help. I told them the reason for my visit and they said I would need a library card. It seems my old library card number was no longer recognized in the system, so a new one was issued on the spot. The librarians were helpful and the procedure was quick and easy.

Actually, I had visited the main library a year or two before, after the gutting. So I knew what to expect. Yet when I climbed the stairs to the main stacks, I was still shocked and disturbed. The books! Where are the books? Gone!

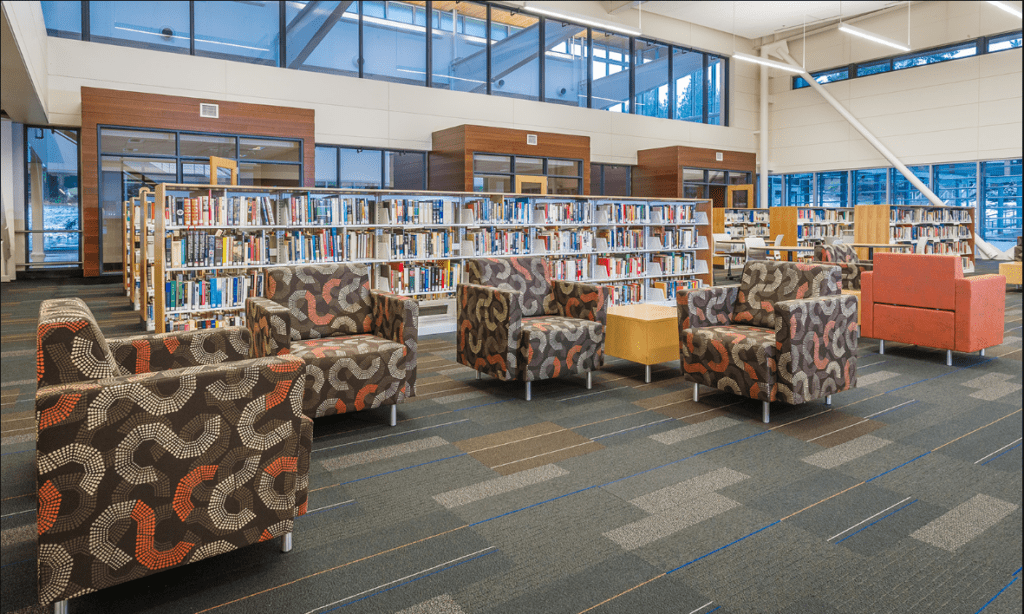

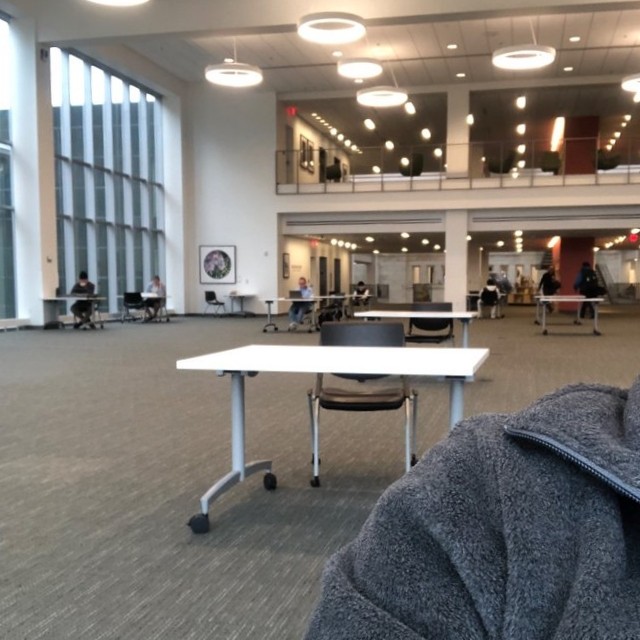

No, not entirely gone. Just mostly gone. There used to be rows upon rows of stacks, the typical tall sort, from floor to ceiling; I believe it required a stool to stand on to get books from the top shelf. Now the stacks are half-sized, like the stacks in the children’s section, as if they simply didn’t have enough books to fill the space—which, I suppose, is now true. At the once-glorious Columbus library, where once there had been more books than in many college libraries, now there are opens vistas of empty floor and (even on a late Tuesday afternoon after school) mostly-unused chairs and tables, which are placed far apart, as if Covid is still raging. As a free co-working space, this sort of thing is rather nice, perhaps. But on second thought, not really: social distancing makes for a cold and uninviting space. There is also a third floor, with more books. But again, the stacks are shrunken, a shadow of their former selves.

I looked at subjects I am familiar with, philosophy and theology. The offerings are now pitiful. I remember thinking, in years gone by, that while not nearly as good as Ohio State’s selection, at least the main branch had a very solid and respectable collection of philosophy books. I was rather proud of my local library. This is all changed. Most of the selections are popular—the sorts of things one might find at the local Barnes and Noble. Most of the classics that could be reliably found on the shelves are gone.

The library has been deliberately gutted—dumbed down and turned into a co-working space. Not just that. It is now a “community space.” The only real glory of the library is the children’s area, which seems to be clean, safe, and well-stocked. But next to it is a vast atrium, through which after-school teenagers and many bums mill about or camp on the floor. A coffee shop dominates the space, and a very small bookshop. While I was using the restroom, I noticed one bum lying on his side in a stall looking up at me sleepily through the floor-level gap. I greeted him and went about my business: who can blame him for being there? It’s a community space. On the second floor is a teenagers’ area, with games and televisions, because as everybody knows, that’s what a library is all about. When I told the librarian that I was researching nonprofits, she (not having anything better to do) rather proudly ushered me to the “nonprofit area,” a rather more elaborate co-working space. But there is nothing there that I could not get elsewhere in the area: access to the library wifi, which is all I needed to have access to the database.

It won’t do to tell me that people read ebooks now. I know that. I’m not impressed by that argument. First of all, not everybody does. And in any case, you can’t browse ebooks the way you can browse stacks of real paper books. Library ebook holdings are ephemeral: you lose the subscription, you lose the books. Paper books require no subscription. And the sense of being among crowds of brilliant thinkers and writers is gone: modern library authors more nearly resemble marketers and influencers.

And the old library serendipity is gone. Maybe that’s the worse part. The library no longer conveys awe and mystery.

By the way, did you know that, especially with Covid, libraries have been joining teacher unions? I want to criticize neither teachers nor librarians because they are not well-paid and they do serve an essential role in society. But library leadership complains bitterly about conservative demands to remove pornography from school libraries; how ironic. “Censorship!” they cry. Should we not more strongly cry “censorship” when they cull thousands of good old volumes from their collections? And surely we will not go too far amiss if we suspect this action of having political motives: other aspects of education have also been politicized, even radicalized, in recent years.

Well, I have an idea. Why don’t libraries invest their resources in buying, well, some books? Why not a full collection of all the classics? There aren’t that many, and they are not expensive, or rather, they can be obtained and printed in inexpensive editions. What I ask here is quite reasonable: have all of the classics in paper form. Why don’t libraries stock the top 10,000 public domain classics, for ease of access, lack of dependence on the Internet, serendipity, and in support of a solid liberal arts education? I calculate around 70 college library bookcases. That would not be that much space: perhaps 750 square feet of floor space. But at least that knowledge would be preserved for the lifetime of those books, which can be quite substantial. Their presence would support the more scholarly public—not a small community—who greatly desire ease of access to such books.

Librarians do care about liberal arts education, right? Surely they do.

Update, September 18, 2024. Yesterday, the Knowledge Standards Foundation launched ZWIBook flash drives. Did I really say the top 10,000 public domain classics? Would you believe that for 50 bucks you can quickly and easily obtain a local, personal copy of 69,020 books? It comes bundled with bespoke software for searching, reading, highlighting, and making notes on them. The books are themselves digitally signed last December 2023, giving you some reason to believe the files haven’t changed since then.

Leave a Reply