Discourse about the soul is ancient, continues to this very day online and in academia, and spans many languages and traditions, with research spanning multiple disciplines and, all told, literally thousands of relevant books. I cannot hope to do all of that justice in this essay, so I will not try. My aim is much more modest: simply to satisfy myself, for now, on two questions:

- What is the soul?

- Does the soul exist?

As a philosopher trained in analytic methods, I will begin by talking about words a fair bit, for the simple reason that this is an excellent way to clarify precisely what the subject is. Some, but certainly not all, philosophical problems can be resolved by carefully examining how we use words.

Let me dive into the first question without further ado.

The Sort of Thing the Soul Is

With any ti esti question (Greek for “what is it?”—famously, Socrates’ type of question), the first thing to do is to circumscribe the concept to be defined or analyzed. To this end, I can think of several subsidiary questions, but here is a good place to begin: Is the soul something different from the mind? After all, the mind is something that many of us acknowledge exists; but if we say it exists, do we thereby affirm that the soul exists?

It does not seem so for the simple reason many people are happy to acknowledge that the mind exists, while believing that the soul either does or might not exist. In any event, the concepts seem to be distinguishable, even if the things themselves are not. And even if I decide they ultimately are the same, it will be good to settle on which concept I take to be my target to analyze, because the words, clearly, have different semantics.

It is relatively easy to concede that the mind exists, because it is a much broader and as it were forgiving concept. I mean, there are substance theories of mind as well as bundle theories of the mind; even behaviorist and reductive materialist theories, which deny any inner experience or “qualia,” have been construed as “theories of the mind.”

Hence the mind is not the thing I want to focus on. The soul, whatever else it is, is irreducibly spiritual, mental, or “inner.” Moreover, while we need not endorse any particular theory of substance, the soul is held to be an object of some sort and not merely a bundle of properties, actions, habits, states, or events; it is correct to attribute properties, actions, etc., to it (you cannot correctly attribute properties to a bundle, I think). It simply cannot be a theory of the soul to say the soul just is some mental event such as the perception of a bird or the memory of a smell, or a state of pleasure or pain, or the habit of thinking, or an instance of cogitation. That is simply not the sort of thing a soul is. Such mental events might, perhaps, be said to occur to or within a soul. Nor can a soul be a “bundle” of many such items. A soul is said to be that to which such events occur, if it exists.

Let me sum up the latter considerations, which probably went by very fast. There are, I propose, at least three things that characterize the concept of the soul, that help to distinguish it from other, related concepts: first, it is irreducibly spiritual and not material, whatever that means; second, it is an object (a proper subject of attribution); and third, mental events such as seeing or feeling pain or imagining are all, at least possibly, things that occur “within” a soul. So if materialism (or physicalism: I use the terms interchangeably) is true, then souls certainly do not exist; if there is nothing like a substance, object, self, or subject of experience, then souls do not exist. On the other hand, it does not immediately follow that, if materialism is false, therefore souls exist. Nor is it very clear to me that if we have an immaterial self or mind that is the subject of experience, that that is the soul. But maybe it is. I will examine that question next.

The Semantics of ‘Soul’, ‘Mind’, and ‘Self’

If I have a pain, or see the clock on my wall, or remember an appointment, we can (although some do not want to) say that I (emphasis on this word) am the subject of such pains, perceptions, and memories. But am I my soul? If so, then my soul is the subject of mental attributes. Now, again, those willing to countenance the existence of minds are happy to say that pains, perceptions, and memories are had by minds and, less often, by selves—but, again, not nearly as often, by souls.

So, is the soul, if it exists, supposed to be the subject of experience—or would it be something else? How we answer that question depends entirely on our specific notions about the soul, but in the Western (Christian-influenced) world, we speak about the soul in various quite relevant ways such as:

- “Caring for the soul”: Ensuring that your moral habits and religious, maybe especially prayer, practices are excellent.

- “A wounded soul”: A depressed or bereaved person, or perhaps a person whose faith in God is weak.

- “With all your soul”: With faithful feeling or earnest motivation.

- “Kindred souls”, “soul-mates”: People who relate to one another, often due to some similarity, at a deep level.

- “A feeling deep in my soul”: An intuition, emotion, or conviction that perhaps you cannot account for but which you feel strongly.

These sorts of phrases indicate that indeed the soul, whatever else it is, is spoken of as the subject of at least some of our experiences, but perhaps especially our deeply-felt emotions and convictions. Can we also attribute evanescent and trivial sensations, feelings, and memories to the soul, or not? I can see a case being made both ways: in describing some slight twinge of pain, we rarely say our “souls” experience such things; we are more apt to attribute such things to our minds or even our bodies (or nerves or brains).

This suggests that ‘soul’, ‘mind’, and ‘self’ differ in function, i.e., the purpose to which they are put in our conceptual schemes. It seems that all three can be the subject of experience. What, then, is the function of the concept of the soul, and how does it differ from the functions of ‘mind’ and of ‘self’?

The usage examples given above suggest that ‘soul’ is pressed into service when we want to speak of our deep feelings, passions, and religious faith. ‘Mind’ is much more general, although in ordinary language it tends to be pressed into service when we are speaking of the intellect, i.e., mental activity involving abstract knowledge and logic; although it certainly can be used much more broadly than that. As to ‘self’, especially insofar as it is used in pronouns like ‘himself’ and as a strict synonym of ‘ego’ and ‘I’ (when referring to one’s own self), this is colloquially pressed into service, rather imprecisely, to mean both mind and body, “the whole package,” and especially as it exists through time. ‘Self’-talk often is used to talk about whole individuals rather than of just the mental or spiritual activity of individuals.

Another important functional difference between ‘soul’ and ‘self’ on the one hand and ‘mind’ on the other is that the former are sometimes spoken of as existing after death—the ‘mind’, per se, not so much. Probably the reason for this is that minds are associated with embodied experience, i.e., with how we interact with the world, beginning with the senses. If we live on after death, the part of us that lives on might not interact with the world, and certainly not through the senses. This might also be why it is strange to attribute passing bodily sensations to the soul.

But just because we in modern colloquial usage speak about the soul this way, it hardly follows that, if the soul exists, it should be considered to be a different item in our ontology (i.e., the set of distinct items that we say exist) from minds and selves (not to mention spirits). I maintain rather that, however these words differ in conceptual or linguistic function, all three are often taken to refer to a subject of experience (understood broadly, meaning a subject of mental attributes), assuming indeed there is such a thing as a subject of experience. Now, it is conceivable that we have two different subjects of experience within us, a mind and a soul; but this specific suggestion is rarely made and I, at least, am not aware of having such a split personality, as it were. I can confirm in my own case that I possess what philosophers call “the unity of consciousness.” I might come back to this issue.

So, although they have different semantic functions, I am inclined to take ‘soul’, ‘mind’, and ‘self’ as synonyms in the sense that they have the same referent, namely, a subject of experience or of mental attributes. The terms refer to the same ontological items. Again, another synonym would be the “I” or the “ego” (which is just the Latin word meaning “I”), as long as this is understood to exclude the body.

Introspecting the Soul

So I say that I or my self is, in a sense, my soul. So what am I? What is my soul? I say in turn that this cluster of semantically related concepts all refer to the same thing, namely a subject of experience. So the soul, whatever else it might be, just is the subject of experience, assuming the subject of experience exists. So if we want to know what the soul is, we should examine what a subject of experience is. There might be, and doubtless is, much more to it than that; but it is at least that.

As it turns out, this is not at all an easy question. We have an intuitive understanding of what it means, and can easily give examples in language that seem to refer to a subject of experience, but explaining what this item is is by no means simple. Whole books are written about it, including one called The Subject of Experience by Galen Strawson. But I have no time to review the literature, and it is not as if I have not already read a lot of the historical source literature about the problem; Descartes, Locke, Hume, and Kant all have important things to say. But I am going to dive in with my own narrative—here goes.

Let me quickly mention the notion that the subject of experience, whatever it is, just is the brain or nervous system. On first glance, this looks like nonsense. The reason is that the brain has a number of physical properties that it is utter nonsense to ascribe to my soul. My brain weighs about three pounds; my soul does not. And while it seems to make more sense to ascribe mental processes like feelings and thoughts to the brain, we are not now talking about a mental process but instead about a subject of experience. Here, of course, is where physicalists say that that is why they say a subject of experience does not really exist. The “feels” of your experience are just what your brain and nervous system is like “from the inside,” so to speak; but there is no immaterial soul or self lying behind it, except as a spurious mental construct. I will return to this view later.

To bring out an insight about the subject of experience, let me draw your attention to the phenomenon of the internal perception of one’s own body, called proprioception. I will spend a bit of time on this; I have a specific reason for doing so.

Proprioception is different both from sense-perception insofar as the senses we use to perceive the external world do not appear to be involved (although scientists have described many systems used for proprioception). If you feel an ache in your legs or a tickling sensation under your nose when nothing is tickling it, or if you feel your body to be hanging upside down or to be in motion or falling, you are experiencing proprioception.

While it is possible to sense specific parts of your body, it is also possible to sense your entire body, as when you have the feeling of dizziness. Just as you can have proprioception of missing “phantom” limbs, such whole-body proprioception need not be veridical (i.e., genuine, accurate); you can have the feeling of dizziness and spinning even when your body is at rest.

As you can see, there are two different kinds of subjects of proprioception: individual body parts and the entire body of which they are parts. This is true whether or not some proprioception (some internal sensation) is veridical.

Now we can draw an analogy. Consider first that we can sense what is going on inside our own minds via the process, or “faculty,” called introspection. Just as there is proprioception of a specific pain in my stomach, there can be introspection of a specific instance of remembering, say, a childhood ball game. But just as we can and do describe proprioception of the entire body (“I’m dizzy!”), can we also speak of introspection of the “entire mind”? And would that not be introspection of the soul?

What would introspection of the soul be like? Again, just as we have a sense of passing internal sensations that are part of an entire body (that we can also sense; “My arm is tingling!”), so also we can introspect various passing thoughts, emotions, and imaginary fears bubbling up from the subconscious, all of which are attributed to yourself. Just as you have a generalized sense of your body quite apart from any specific sensation you feel within it (or about it; “My whole body is tingling!”), you can have a generalized sense of your whole mind, or soul, or yourself.

How would you go about trying to persuade yourself that you have the capacity of such “whole mind” introspection? In much the same way you persuade yourself that you have “whole body” proprioception: you cut out localized, specific sensations. After ignoring all the various pains, pressures, positional information, etc., about your body, there remains a sense of your whole body. Consider something similar but with regard to the whole mind. It helps if you close your eyes and retreat to a quiet, unbusy place—if you ignore the passing thoughts, imaginings, memories, and perceptions, as you attend to what is passing in your mind, you do, contrary to Hume, find that you are aware of something in addition to all that.

The proposal, then, is that that is you: your listening self. Your soul.

If this is correct, then it is perfectly natural if it said to be in prayer or meditation that we best come in contact with our own souls. Both of those involve tuning out the “blooming, buzzing confusion” of both external sensations and undisciplined internal thoughts, and instead focusing on the “still small voice” of your conscience or best self in conversation with God, in the case of prayer, or on nothing at all except the bare self, in the case of much of meditation. Even when we are lying in bed with our eyes closed, waiting for sleep, behind the mad rush of worries and happy thoughts, I propose we can more easily distinguish in our awareness that which has the thoughts.

We are, I maintain, well acquainted with our souls, even if we cannot articulate this acquaintance very well. Of course, the soul- and self-deniers will say that this hard-to-articulate sense of ourselves does not show that there is in fact a soul. It is, at best, a piece of highly fallible evidence, they will say. But I maintain, to the contrary, that there is no reason to doubt this internal evidence. The sense of our selves—and that it is our selves, or our souls—is as clear, if we know how to attend to it, as any other evidence we can have from the senses or from introspection.

It was on the basis of something like this introspective argument that Descartes concluded, in the Second Meditation, “I exist.” And his focus was indeed on himself and the nature of this “I” that exists. The mind, he thought, was better known than the body. As he puts it:

What is the ‘I’ that seems to perceive this wax so distinctly? Surely I am aware of myself not only much more truly and certainly, but also much more distinctly and manifestly. For if I judge that wax exists from the fact that I see this wax, it is much clearer that I myself exist because of this same fact that I see it. Possibly what I see is not wax; possibly I have no eyes to see anything; but it is just not possible, when I see or (I make no distinction here) I think I see (cogitem me videre), that my conscious self (ego ipse cogitans) should not be something. … Further, if the perception of the wax is more distinct when it has become known to me not merely by sight or by touch, but from a plurality of sources; how much more distinct than this must I admit my knowledge of myself to be! No considerations can help towards my perception of the wax or any other body, without at the same time all going towards establishing the nature of my mind. And the mind has such further resources within itself from which its self-knowledge may be made more distinct, that the information thus derived from the body appears negligible.

Descartes, Second Meditation, trans. Elizabeth Anscombe and Peter Thomas Geach

Philosophers have long contradicted Descartes, saying that all he introspects is a sensation (or imagination, etc.) of the wax, and not himself, i.e., his self. But it is clear from a close reading of the text that Descartes is very specifically claiming to know not merely a sensation within him, but indeed his self. He does not say he is “thinking” or “thoughts,” but a “thinking thing”; he is a res, not merely cogitans. And while he does not use the language of “introspection,” it is clear that he and his argument depend on introspection of himself.

I can endorse this in my own case: that these passing thoughts I have are occurring to me, to myself. I would quite naturally use the word ‘I’ in attributing them to the object to which they occur, to, as it were, their owner. I only go a bit farther, when I “close my eyes,” “stop up my ears,” and “turn away my senses from their objects” (as Descartes puts it in Meditation Three), and claim that I can positively introspect that whole mental self, just as I can without any trouble “propriocept” my whole physical body.

Does the Soul Exist?

If we can (veridically) introspect the soul, then of course it exists, just as you could not (veridically) perceive a tree without the tree existing.

What we have not established, however, is that the thing we decided we could introspect deserves to be called “the soul.” I said earlier that the soul is (1) irreducibly spiritual, (2) an object, i.e., proper subject of attribution, and (3) has mental events such as thinking, intending, remembering, and perceiving occurring within it. It seems to me this is a good set of requirements for a soul, so if we have good reason to think something satisfies (1)-(3), then it is a soul.

I can introspect, I argue, my “whole mind,” i.e., something analogous to proprioception of my whole body. I can also introspect that various mental events occur within this thing I also introspect; i.e., I am aware of pleasures, pains, and ideas occurring to (or “within”) myself. All I mean is that when I, for example, remember a pleasant walk from earlier in the day, and then close my eyes and introspect my “whole mind,” then of course the thing that I am introspecting just is that which has the memory: it is myself. So this object of introspection satisfies (3). But at the same time it satisfies (2), because it is I who remember.

The only thing left to establish, at least to my present satisfaction, is (1): that this soul is “spiritual,” whatever that means; and to establish this, it suffices, I think, to establish that it is not physical. I raised this question earlier when mentioning that my soul does not weigh three pounds although my brain does. This line of thought is worth spelling out in more detail.

This is a commonly-employed argument for dualism: that there are things true of the mind, or mental events, which are certainly not true of physical (brain) events. I can introspect the experience of yummy delight in ice cream, but in so doing, I am not coming to know any brain event. Even if there is some assignable brain event that invariably accompanies pleasure in ice cream, that pleasure, which is wholly accessible to me, is utterly unlike any firing of neurons.

I once, when I was a firmly committed physicalist, thought I had a response to this: there is no need to be able to introspect the appearance or anything, really, about the underlying physical state of a mental event. Having a certain experience just is the system’s natural response or operation when a certain corresponding brain event is occurring. There need be no expectation of an ability to introspect anything about the underlying brain event.

I now see, however, that I was only grasping at straws with this response; I was not taking the problem seriously enough. The physicalist’s claim, again, is that mental events just are brain events. But if that is true, then when I am coming to know a mental event, then I am coming to know a brain event. On the physicalist’s view, they are supposed to be one and the same; but, clearly, they are not the same, since I can be intimately familiar with the qualities of some introspected experience without knowing anything whatsoever about the brain. There just is no easy response to this argument. It is simple, to be sure, but it is powerful.

Now, I cannot pretend that this brief discussion puts physicalism to rest for good. I state it here only by way of explaining to you, the reader, and to myself why I have come to this conclusion now. While being irreducibly mental might not be quite the same as being “spiritual” or “of the soul,” I have already established that the soul is held to contain (or be subject to) “mental” events just as the “mind” and “self” are. Indeed, I am satisfied, so far, that the soul, the mind, and the self are the same, because again I doubt there is more than one subject of experience within me. So if various mental events are “irreducibly mental,” that by itself establishes that they are “irreducibly of the soul,” or spiritual.

So the “whole mind” or soul we can introspect satisfies condition (1) as well. “I” am a subject of experience, of various mental events, and these are indeed irreducibly mental.

So the soul exists.

The Knowability of the Soul

We know a great deal about “what goes on” in our own souls or minds, particularly if we are at all reflective. If the arguments above are correct, we can (and often do) also introspect a soul—something that is properly called our own soul. And we can know that we introspect it, too. But that is not to say that we understand what our souls really are. We have no idea of what “soul-stuff” might be (in ancient times, it was held to be “breath”).

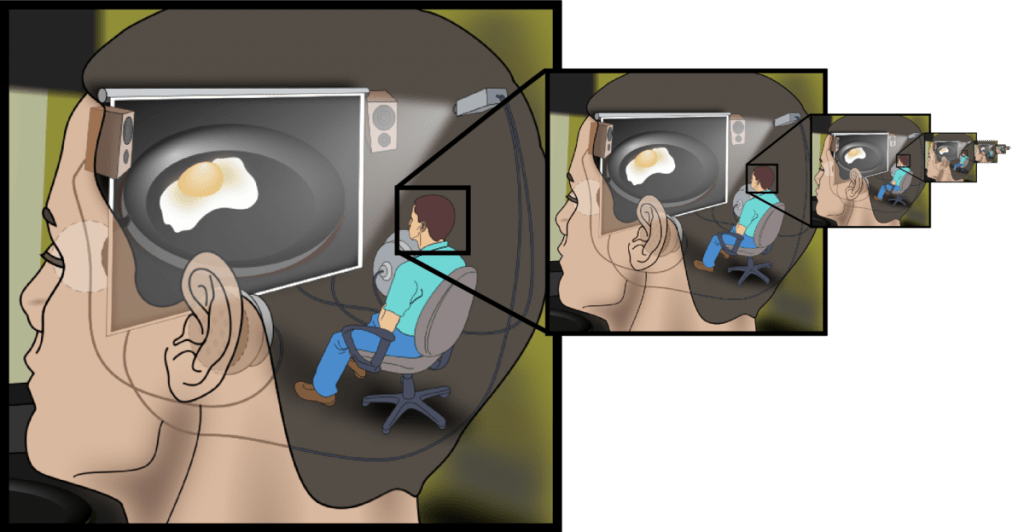

It is around this point in the narrative (if not much before) that we are likely to see an outburst from physicalists, who see exasperating, willful ignorance at play here. After all, they say, we are learning more and more about exactly how the mind is encoded in the brain. We can locate specific mental processes in specific parts of the brain. We are learning more and more about the biochemistry of the brain, and thus how specific drugs affect the brain. For 25 years we have even been able to communicate via computer connections with the mind via the brain’s predictable architecture (i.e., the so-called brain-computer interface). Scientists have even observed how the MRIs change when a subject is introspecting rather than paying attention to sensory information. What is this if not the discovery of ever greater detail about the underlying physiology of the mind and of evidence that undermines the existence of a soul?

Maybe more to the point, why is there any need to posit the existence of some spiritual feature—a “subject of experience” that is a soul—only to declare it to be unknowable? Why should the physicalist not laugh this claim to scorn? The soul does seem unknowable, indeed; but perhaps the reason for that is that it does not exist. And there something else to justify such scorn, more than just a failure to respect Occam’s razor (“do not multiply entities unnecessarily”); there is the keen awareness by an irreligious, rational scientist confronted with a belief that shows every sign of being motivated by the wishful thinking of religion. After all, it is precisely the belief in the soul that permits us to believe in life after death, in a higher state of being (e.g., existence in heaven), and indeed in God (or the gods), who is (or are) supposed to be a “great soul” who can help and comfort us as, various religions have repeatedly confirmed, nothing else can. Secular, scientific types infer that not only there is conclusive evidence against the soul, but also that the belief in the soul is transparently biased and irrational. How can the soul be defended against such an onslaught?

The physicalist is well advised not to be too smug. For one thing, their view is far from univocal or a consensus position. Other philosophers and scientists think that, despite progress in brain science, we will never “crack consciousness,” a problem that bears a close relationship to understanding what the soul is, insofar as what David Chalmers called the “hard problem of consciousness”—the subjectivity of experience, the “what it’s like”-ness of consciousness—is evidence that consciousness will never be reduced to any physical thing or process. A few scientists even think we can learn about the soul from quantum physics—I do not quite understand why they think we can, but a fair few seem to think so.

Strange strands of physics and psychology might go so far as to have people doubt the existence of physical objects. It may be more apt to take any such new frontiers not as especially plausible, let alone established, as an interesting illustration of why we need not be terribly disturbed if it should turn out that we still do not know what the soul is, despite our learning more and more about psychology and brain science.

For all the physicalist’s smug scorn, he has no good response to the Cartesian argument that we can introspect the soul with a high degree of certainty, in much the same way we have proprioception of the whole body. This is because such introspection is data, not theory. To be clear, there is theory involved, namely, that what is introspected deserves to be called the soul. But that is something I have established, so far, to my own satisfaction, and in any event, the data gathered from such acts of introspection cannot be gainsaid, as far as I am concerned.

As I said, there is a great deal we know about our souls—i.e., about what they do and experience. The thing we do not know is what they are. This is no more a confession of intellectual bankruptcy than would be a 17th-century scientist observing confidently that there are physical objects without knowing that they are made of atoms.

The nature of the soul, and the many and detailed features of subjective human experience, “spiritual” and otherwise, is simply not discoverable by any examination of physical stuff. That is merely a reflection of the fact that subject features of experience are not physical. And that means, in turn, that the scientific methods that work only on physical stuff will not work on mental or spiritual stuff. Again, we cannot infer what anything is like from the most advanced and complex understanding of the brain and nervous operations. An MRI might well let a scientist “read thoughts,” but no brain scan can never reveal the subjective experience of those thoughts.

Remember too that there are many states the mind or soul can be in. Philosophers may say the soul is a “simple” thing, but how it processes and interacts with the world is anything but simple. It is not as if the rich experiences of fully human lives, and everything they entail, are trivial. No, the stuff of our souls is precisely the stuff we write our greatest literature, poetry, and philosophy about. This is what inspires those religious sentiments that lead people to worship, sacrifice, and repent.

We, those of use who believe in souls, need not be irrational or anti-science. I do not wish to deny or minimize any of the scientific discoveries made about the operation of the brain. I concede entirely—why would I not?—that our inner lives are deeply tied up with the operation of the brain, somehow. I am sure Descartes would not have wished to deny that, either, had he learned the details. I remember my college class laughing in 1987 when we first read Descartes, since he thought the seat of consciousness was the pineal gland. I think we are not apt to laugh quite so much anymore, since we discovered a place in the brain that seems to be responsible for consciousness, the claustrum, can be stimulated in a way that causes instant unconsciousness, as if it were an “off” switch for the waking mind. It turns out that the claustrum is not that far from the pineal gland; Descartes was not so wrong.

There is no amount of discovery of the neural concomitants (things occurring together: I choose the word deliberately) of mental phenomena that will render introspection and proprioception irrelevant. Data from these purely mental abilities of ours will always undergird any future conclusions of brain science; we can “read thoughts” (in the very imperfect way we can) by examining MRIs only because experimental subjects have, in the past, informed scientists about what they were thinking. Brain science is downstream of introspective psychology, and it always will be. Physicalists must never forget this. Discoveries made about brain science, therefore, cannot refute the datum that I am aware of my soul.

Conclusion

To claim that the soul exists is typically to imply a raft of other claims: we will live on after we die; we might go to heaven or hell; our souls might leave our bodies; our souls might come under spiritual attack from demonic forces, and receive spiritual assistance from angelic or divine forces; we are similar to God the Father and the angels precisely in that we have souls. I have not proven or even given so much as a lick of evidence for such claims. Am I uninterested in them? Surely I must be interested, because if I am not, what is the point of insisting on the existence of the soul in contradistinction to the mind or the self? Only soul-talk carries such baggage.

I am indeed interested in those claims. Moreover, I think that separate arguments can be made for them. While they need the soul to be independently established, as in this essay, the conclusion of this essay would be greatly strengthened if these turned out to have (otherwise) independent evidence in their favor. For example, if some interesting evidence for “life after death” can be adduced, that would require the existence of the soul, and in so doing make the case for the soul stronger.

There is one essential philosophical question I have entirely ignored in the above, and that is what the relationship is between the soul and the body, if the soul exists. I can happily concede the effect of brain-altering drugs, for example, on the mind—and hence, the soul. Similarly, injury, diseases, and surgery done on the brain can all greatly change how our minds work—and hence again, the soul. It seems impossible to gainsay that the soul causally depends on the body. Only the few adherents of parallelism (mind and body are miraculously coordinated in advance), like Leibniz, and of occasionalism (God coordinates things on the fly), like Malebranche, bravely deny a causal relation. But a causal relation seems perfectly obvious for more prosaic reason, such as that the perception of a red ball in my soul is caused by the red ball I see.

In philosophy of mind, some fans of qualia (“raw feels” or subjective experiences that cannot be reduced to anything physical) try to dodge the problems here by saying that only properties are mental, not any objects or substances. (This is called property dualism.) But if you believe in the soul, you believe in a spiritual substance or, if you do not endorse the metaphysical complexities of “substance” talk, then a spiritual object. And then you endorse what is called substance dualism, precisely the “common sense” theory that Descartes defended. Descartes is the whipping boy of practically all Phil 101 classes, which love to poke holes in substance dualism. But this is not to say it is impossible to defend substance dualism in the 21st century; many Christian philosophers, perhaps most notably Richard Swinburne, do just this. Perhaps I will update this essay at some later date with further discussion of the question.

For now, though, I cannot say I have proven that there is a soul, but only rehearsed some good reasons to think there is one.

Leave a Reply to Seth Finkelstein Cancel reply