At the heart of Christianity is a set of doctrines that appear to be deep and compelling for over a billion souls on earth. But divorced from their context, the same doctrines can sound primitive, ridiculous, unfair, and even insane to the modern mind. In this essay, I want to see if I can do justice to these basic Christian theological tenets. Note, though, that my intended audience is nonbelievers and people deeply confused about these doctrines. Any Christians in the audience are welcome to correct my mistakes, of course.

If you look online for answers to the questions, “Why did God require blood sacrifice in the Bible?” and “Why did God sacrifice his own son for our sins?” then the following are the sorts of confident yet (to the uninitiated) puzzling claims you will find in the answers:

- God is absolutely holy and good.

- God created man in his own image and loved him dearly.

- This meant that God gave man free will and thus the opportunity to sin. And sin he did—a lot.

- God, being holy and good, was absolutely enraged at the evil men did.

- So God allowed men to perform animal blood sacrifices (and food sacrifices) that atoned for (covered over) their sins. So God forgave them. But eventually, this sacrifice became a meaningless ritual that did nothing to appease God’s righteous wrath.

- So God came to earth (which was his plan all along: see Old Testament prophesy), incarnated as his “only begotten son” Jesus Christ, in order to make a “perfect sacrifice” of himself.

- This perfect sacrifice atones for our sins just as ritual blood sacrifice once did, but in a more perfect way and only if we accept Jesus’ sacrifice, which entails believing that Jesus is the son of God. And if you do not accept this sacrifice, you will burn in eternal hell fire.

Many of these points—especially 5-7—sound utterly bizarre to the modern secular mind lacking any theological context. At the risk of sounding heretical, a risk the nonbeliever is all too willing to take, God sounds like an unfair and irrational bully. “So,” the atheist snarks,

your God creates these playthings that he loves, even though he must know they will be broken and nasty, so he gets mad at them. That makes sense. Then, instead of punishing them, he allows his playthings to substitute dead and bleeding animals in their place. Sure, that makes sense too. Then your God comes to earth and allows himself to be killed on a bloody cross—essentially, pretending to kill himself, since he comes back to life after three days—and this makes the bloody slaughter of animals unnecessary, never mind that it was bizarre that it was ever necessary in the first place. But you want me to accept this “gift” I didn’t ask for, and then…I won’t have to slaughter animals anymore? And that will make all my bad actions all right, no problem? And that is why I have to believe in Jesus? And that will stop me from burning forever in hell? No, really, that doesn’t make any sense at all. Your religion is absolutely insane.

Anti-Christian atheists have often indulged in variants on this theme. If their criticism is rooted in ignorance, it would be very important for Christians to remove that ignorance. Indeed, all believers must eventually, sooner or later, ask, “Why sacrifice, of all things?” They deserve a good answer. Since there are still a lot of believers, and since, contrary to the atheist, the average sincere Christian seems to be perfectly sane, I think that the atheist must be failing to understand something rather important. But what?

As it happens, this whole body of doctrine is easy for anyone misunderstand. I am sure I do not understand it all perfectly myself, but in any event, here is my explanation of the seven claims above. By the way, in the following I do not argue for the claims or to justify them rationally, but only to explain what they mean. But the proper explanation, as we will see, makes them more credible—or at least not “insane.”

1. The Holiness of God

From a metaphysical point of view, if God exists, the distinction between mind and body is not the most fundamental one. The most fundamental distinction would be that between God and the creation. Spacetime cannot exist without matter, so if God created all the matter in the universe, he also created spacetime and lives outside it, just as the theologians say. More to the point, if God is the creator of the universe, he cannot be part of or have an existence that is dependent upon the universe. All this means he exists outside of space and time (he is eternal) and exists independently of the universe.

To say that God is holy, as in the original Hebrew word (qodesh), is just to say that God is utterly apart from his creation. That he is holy in this sense is plain from the previous paragraph. But if that is so, then why should the holiness, the “apartness” or specialness of God as described, make God also an object of veneration, of something perfectly good?

I am not entirely sure if this is quite orthodox, but let me share a theory. Think of some things for which we are praised the most: writing a great book, making a world-changing scientific discovery, building a tremendously useful invention, and let us not forget raising a good child. People who are most famous for such achievements are received by lesser mortals—maybe especially by young people and their admiring students—with something approaching veneration.

So, whether or not you do, imagine you actually thought God existed. He actually created everything you see around you. If all you see around you is man-made, remember that God made men. He made all of nature in all its complexity, all of the earth, all of space. He wrote the laws of nature that scientists think themselves clever for discovering. Imagine there were an actual person who made all that—remember, you must at least pretend to believe, if you want to understand this—then how much more would you venerate such a person, and how much higher, and apart from you and your concerns, would such a person seem to be? Much more. Your respect would go beyond veneration to worship, worship of a being the holiness of which is obvious and awesome.

2. Man Created in the Image of God

God and creation are mentioned in the first sentence of the Bible. In the first chapter, as God’s final and greatest (mentioned) act of creation, he made man “in our image, after our likeness.” (Genesis 1:26) Elsewhere in the Bible it is made clear that, although God might “appear in his glory” (e.g., Psalms 102:16) and is “made flesh” (John 1:14), in his own person and nature, God is a spiritual being. So it is understood that our souls in some way resemble the great soul, or spirit, that is God.

It is not surprising then that God might have “blessed” the first man and woman (Genesis 1:28), and counted us among those things in his creation that were definitely “very good.” (Genesis 1:31) Indeed, throughout both testaments God is said to have great affection for us. This is not surprising, I say, because if you had created the whole dumb mechanical universe and then whipped up some talking, intelligent beings, complete with souls like the great soul that you are yourself, then you might have a special place in your heart for this most complex and interesting of creations (well, except for the angels). You might well consider them your children, to want the best for them, and to want them to be, well, good.

3. Man’s Misuse of His Free Will Means He Is Fallen

As the Garden of Eden story expresses, God was pleased to walk alongside Adam and Eve—perhaps only in spirit, or perhaps he was “spirit made flesh” here too. The living was easy and the rules were few: do not eat of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. All was well until the humans ate of that tree. For this, they were cast out of the Garden and made mortal (in the Garden, the fruit of the Tree of Life made them immortal).

What are we to make of this? Why put a corrupting Tree in the Garden? If it must be there, why even make it possible for man to eat its fruit? And if this is the Original Sin, why think it is fair for us to be tainted by the Adam and Eve’s sin? Generally, why would God make man only to cast him out and let him shift for himself? As it turns out, the explanation for these questions works regardless of whether you think the Garden of Eden was spiritual (i.e., not a physical place), metaphorical (a didactic symbol of our first relationship with God), or an actual place in Mesopotamia.

There are different ways of understanding the image of the Tree and the doctrine of Original Sin, but here is how I currently think about it. God could have created more instinct-driven animals or automata, but he chose instead to make beings with souls and free will. What it means to have free will is to have the freedom to choose from a variety of options, and in life, indeed, sometimes options are very bad. The “Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil” was not an ethics class in a piece of fruit. The place where they were, and the innocent things they were doing there, were already good. The fruit of the tree provided an acquaintance with evil—forbidden, because corrupting. Knowledge of evil was knowledge of how to be evil.

This is doubtless a metaphor, but I think it is a metaphor for man’s free will itself. God’s will, being perfectly good, is such that simply doing anything he says not to would be bad. Merely eating a certain piece of fruit, regardless of what Adam and Eve did, made rebels of them—and the one person you do not rebel against is God.

God, in his infinite wisdom, did not want anything that had chosen evil action in his holy presence. God is, again, absolutely holy. He is much greater, much farther “above us” in power and goodness; as the creator of all that is good, his actions are the very standard of goodness. Therefore we had to leave his presence. He wanted to have nothing to do with evil.

4. God’s Wrath

Now this—the fact that there was any punishment at all—might in itself be hard to fathom, especially for those of us with a very permissive upbringing and living in a very liberal society. Why should God, if he is so much higher than us, care about a few human foibles? Why not let us stay with him, sins and all? And if we smell bad, then why the wrath? Why the threats of punishment, and indeed of eternal hell fire (references are throughout the Bible)? Why does God care so much about every little sin? What about equity—making the punishment fit the crime? Heck, you might wonder, what makes God think he even has the right to judge us?

Let us begin with the latter question. Perhaps the most important thing to notice is an obvious consequence of theism itself, but which secular minds have difficulty wrapping their minds around: if God created us, particularly if we are among his highest creations and made in his own image, then he regards us as his to dispose of. Jesus compares us to sheep and goats (e.g., Matt. 25:33)—herd animals of which he is the shepherd.

The liberal frame of mind naturally wants to regard the relationship between two souls, yours and God’s, as one of equals, but that is not how God views it and, surely, his reported stance is perfectly just and understandable. On the view we are examining, God is not your parent. He created you. You are literally his creation and living in his creation. So he clearly has the right to stand in judgment of you. You are his to dispose of.

Notice, I am saying this about a creator and a creation. The point does not apply so obviously between parents and children, for example. It applies to God and to you because he shaped of your very nature and reality.

Very well, even if we concede that God has the right to be our judge, why should he care about our sins? Why would he want to act as our judge? The answer is that, again, he is holy. That he cares at all can be seen—if God is the author of human nature and the human situation—in the fact that standards baked into the creation itself. That is, a certain pattern of honest and responsible behavior will, generally, lead to success. A contrary pattern will lead to failure. But these are just the natural standards for happiness that can be inferred from human nature and the human situation. God’s final judgment, by contrast, is based on his holy and perfect standards—is own standards, not those of his creation and certainly not those of our whims or preferences. He judges us by his own impossibly high and perfect standards.

Why? Why not judge us by a lowlier standard? This seems like an important question, and I am not entirely sure, but I have a theory that is maybe in line with Christian doctrine. One thing is clear from the scriptures: God wants us in his immediate spiritual presence. That is part of his plan. But clearly, you are not ready. He wants only perfect things in his presence. But why? Perhaps he could tolerate a bit of slop. No?

Here is the thing: scripture also makes very clear that, on the Christian view, you are still under construction, still being, at least spiritually, created. The Bible is full of references to God’s improving, testing, helping, and judging us. Why? Well, here is another point to consider: one of the biggest reasons some people have for doubting the existence of God is called the Problem of Evil. That is, why would a good, indeed perfect, God create something with so much imperfection and even evil in it? Answer: he would not. He is not finished with us. He is perfect, and he wants us to be perfect, like him—not merely “very good.” As Jesus said, “Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect.” (Matthew 5:48)

But if you bear in mind that God is omniscient and omnipresent—he knows all and can be found everywhere in creation—and if you consider that he surely regards our world as part of what he intends to be a perfect creation, it follows that his work is not finished.

So, in short. Question: How could a perfect God create an imperfect creation? Answer: he could not. Having finished the initial creation of the heavens, the heavenly host, the earth, and man, is still in the process of creating, i.e., by perfecting fallen man. God is a perfectionist, and he is not done with us yet.

And if, in the end, you are not made perfect, you will not be part of the creation when he is finished. That is a key to understanding much of this.

God’s perfectionism perhaps allows us to understand his wrath: it is a tool to improve us. Whether his anger in any way resembles human anger is unclear. It is certain that his anger is not out-of-control or irrational. Certainly, unlike human anger, it is completely well thought out and, as he is our creator, perfectly just.

(By the way, I am aware that more argument is needed here: it seems prima facie possible for the creator of this universe to be unjust, like a cruel master. But this is a bit of a side-issue and not as challenging as the rest.)

After decades of secular cultural forces telling us that all anger is bad, that there is no objective morality, and that God does not exist, the very idea of justified (and frightening) moral outrage from an deity seems strange and foreign at best—positively archaic.

But it certainly makes sense, given the Christian doctrines outlined so far. Given those assumptions, it should be neither surprising nor particularly objectionable.

The only seemingly problematic issue left on this head is the notion that God will burn damned sinners forever in hell fire. This, in my humble opinion, has always seemed extremely hard to reconcile with divine justice. Why would God torture finitely sinful souls for an eternity? If God is aiming for a perfect creation, it seems their presence in Hell will still be sullying creation. Why not simply eliminate them after an equitable length of punishment?

My view for now is that a respectable case can be made that the Bible does not require eternal torture in hell. This is a view called annihilationism. A few things make it tenable. First, the modifier “eternal” when applied to hell fire might refer to the fact that “the fire is not quenched,” i.e., it is always stoked and ready to destroy a damned soul. Second, the usual Greek word for hell, gehenna, refers to a valley near Jerusalem where worthless trash was burned and destroyed. Third, when the the Old Testament contrasts the saving redemption of the Lord with the other fate, it often describes it simply as “death,” “the pit” (e.g., “the pit of decay”), or “destruction.” This entails that what God offers the faithful is eternal life, while the other option is utter and final destruction. Finally, in Revelation, it is only the Devil, Beast, and False Prophet and their minions that are held to suffer forever in the Lake of Fire. (Rev. 20:10, 14:9-10) The Lamb (Jesus) is said to be witness to this—but surely he would not be on hand for an eternity as well. Of “anyone not found written in the Book of Life,” they are only held to be “cast into the lake of fire.” (Rev. 20:15) Perhaps their souls are quickly destroyed in the lake, rather than being tortured forever.

Anyway, I say only that a case can be made for annihilationism, not that I am quite persuaded of this interpretation. If that is not correct, perhaps there is some way to justify inflicting pain eternally, but I have to say it sounds quite unlikely.

5. Atonement Through Sacrifice

Very well. God is perfectly good, and man is created in his image, with free will and the capacity to do evil as well as good, and in fact man’s nature is to be deeply sinful. Being perfectly good is too difficult for anyone to pull off. This incurs God’s wrath because he applies his own standards to us, as we are among the highest parts of his creation, and he wants us to be able to live with him; besides, being perfect himself, he wants all parts of his creation to be perfect.

So when we do sin—according to the Old Testament—we must atone for that sin, and the way to do that, as laid out particularly in the book of Leviticus, is to sacrifice. This may sound strictly pagan, but it was also part of Judaism, and in fact the concept of sacrifice is central and crucial to both Judaism and Christianity; it is not a side-issue.

But why? Supposing atonement to “wipe away” or “wash” or “cleanse” sin, as the Bible repeatedly puts it, why would it? And why sacrifice—killing and spilling the blood of animals, of all things? If we in our modern age are to take this quite seriously, there seems to be no way to make it sound anything other than primitive, if not positively insane.

Well, that is certainly what I would have thought. To my own amazement, however, I think I have been able to make sense of it. A large part of the problem is with animal sacrifice; but the crucifixion of Jesus put a permanent end to that as a practice. Why? I will have to try my hand at explaining that as well.

But first things first. “Atonement” (in Hebrew, kippur) is often explained by various analogies such as repaying a debt, making whole a lender or someone harmed, making up for a failure, and making reparation. In short, a wrong was done, a debt was incurred, or something was lost; accordingly, he who was wronged, lent money, or owned some lost thing must be compensated fairly. So atonement seems to be somewhat of a legalistic concept and closely associated with justice. Someone who avoids sin (for which atonement needs to be made, as we will see) is said to be righteous, i.e., just and blameless.

It is not debt but sin—i.e., violation of God’s laws—that is said to require atonement, not only in the Old Testament but also in the New. Why? Why does God require atonement?

Notice, atonement is not precisely the same as punishment. Old Testament law provides for punishments as well as sacrifice in response to sin; a person was in fact supposed to pay restitution for wronging another person, only then seeking forgiveness from God through the sort of ritual sacrifice called a guilt offering (Leviticus 5:16). The purposes of punishment itself are not quite so mysterious, and well discussed by philosophers; theories include prevention of further lawbreaking, rehabilitation or moral improvement, and indeed retribution or “paying your debt to society,” which is something very much like atonement.

Atonement, associated as it is with “wiping away” sin, “purifying” iniquity, or “cleansing” unrighteousness (all synonyms, as near as I can tell), is something different. Atonement is necessary to make things right not with the person you offended, not with society as a whole, but with God, because your sin is a violation of the goodness or perfection that a perfect God expects. So what is that all about?

Let us take a step back at this point and observe that sin (iniquity, wrongdoing, lawbreaking) can indeed have terrible effects on our own souls, on our victims, and on society at large. From a theistic point of view, it also has a terrible effect on something you might not have noticed: it sullies God’s creation. It dirties you, one of his highest creations. It spoils the relationships you can have with others, which is another thing God specifically has in his care. It soils things of God that should pure.

There is, in short, a divine dimension to morality and its lack that atheists cannot, of course, be expected to acknowledge. In a theistic conception of God, he is not a bystander in his creation. Indeed, he is very much involved, and again, he is a perfectionist: when he is done purifying it in his “refiner’s fire” (Malachi 3:2), he expects his creation to be perfect. (Again, this looks to me to be a key part of a Biblical solution to the Problem of Evil.) But again, he does not want robots. He wants an interesting world of free, intelligent souls in communion with him; hence he wants us to participate in our own purification.

I would like to impress on you that this is not crazy at all, if you are in the habit of holding yourself to high moral principles. Many of us mentally revisit our past infractions with mortification and horror. Things we did even as long ago as childhood we are embarrassed by or even, if they are particularly bad, endlessly sorry for. You might even say they have left a mark on our souls. The Bible is a book for morally broken—but also morally ambitious—people, people who feel sullied by their own wrongdoing or crimes and wish they could get past them, but never can. This is why Jesus spent so much time with “sinners and tax collectors.”

All right. So the law, atonement, and sacrifice are essentially tools that God established in order to perfect humanity. How would animal sacrifice be expected “purify” us? That bit still does not make sense, for all I have said so far.

On the surface, the sacrificial victim is a proxy for us. God literally demands blood as a “sin” (atoning) offering and to purify us—but he is willing to accept the blood of a beast that is offered in our place. “But why?” the atheist demands. “This still sounds bizarre. Why would an all-powerful, all-knowing God accept a lamb’s blood (for example) in place of ours, and why would he want blood, of all things, in the first place? He looks literally murderous and bloodthirsty!” Or so say the atheists in offering their uncharitable interpretation of the situation.

It will be instructive to explain what is wrong with this complaint. There is no dumb animal or stuff, like a lamb, lamb’s blood, or grain, that we can offer God that, being all-powerful, he cannot create himself. As a spiritual being, he would have little use for it. Moreover, he knows perfectly well that the blood of a lamb, for example, being much less important than humans, can be no literal substitute for our own lives.

That means, of course, that the meaning of the sacrifice must be symbolic, not literal. While God was no doubt watching carefully, the symbol was not meant to work a change not in him (apart from propitiation; more on that later, perhaps), but in us. The blood is the blood of life. This was a reminder of how seriously God treated sin: as can be found throughout the Bible, God regards sin as a serious matter indeed, a matter of life and death: as Paul put it in Romans 6:23, “The wages of sin is death.” God himself supernaturally carried out a death sentence on people in many places in the Old Testament (see Sodom and Gomorrah, Nadab and Abihu, etc.).

It is not hard to see how sacrifice might have been expected to work a change in the Israelites. First, God had made it repeatedly clear that he took this sinning and atonement business very, very seriously. The fiery fate of Nadab and Abihu—who merely failed to follow protocol in offering a sacrifice—underscored how deadly seriously God took this symbol, or rather, how seriously he wanted his chosen people to take it. The sacrificial sheep or goat or cow or bird, being unblemished (a requirement), was actually something of value to the people. That is why “sacrifice” today, in English, means giving up of something of value in order to achieve some end. Moreover, many of the offerings could be (and were) eaten by the temple priests: the offerings were the people’s way of paying tribute to Jehovah by way of supporting his earthly representatives and those tasked with the serious business of atoning through sacrifice.

The problem is that, as the years went on in Old Testament times, the symbol of sacrifice often did little good. Soon enough, not just the people but the priests themselves performed sacrifices in a perfunctory manner, in a way divorced from their meaning. It might originally have been meant to work a change in the Israelites, but ultimately the change was not enough.

It is, perhaps, strange that God would have chosen such an imperfect sacrifice at first. Surely it was obvious that God did not deem the lives of the animal victims equivalent to human lives. Besides, he absolutely forbade, and reserved his hottest wrath, for the pagans, and for the Israelites who adopted paganism, who practiced substitutionary human sacrifice. In other words, it would have done absolutely no good to kill one person in place of another, in order to propitiate God’s wrath. That would only have made him more wrathful.

Besides, if the whole point of atonement was to “cleanse” or “purify” us of our sins, it certainly was not having that effect. Why would it? Animal sacrifice, it seems, served only to make us take God’s law much more seriously than we would have done otherwise. God apparently tolerated sin, period. Indeed, he was willing to tolerate and forgive—one of the things that David and wisdom literature repeatedly thanked God for was his mercy, forgiveness, and being “slow to anger.”

But for a divine perfectionist, sacrifices that worked only an imperfect effect in the Israelites was not good enough. Clearly, a better sacrifice was needed. The oft-empty gesture that animal, food, and drink sacrifice had become was to be replaced by one final sacrifice, that could never be regarded as an empty gesture. And that was because the sacrificial victim was God himself made flesh.

6. The Lamb of God

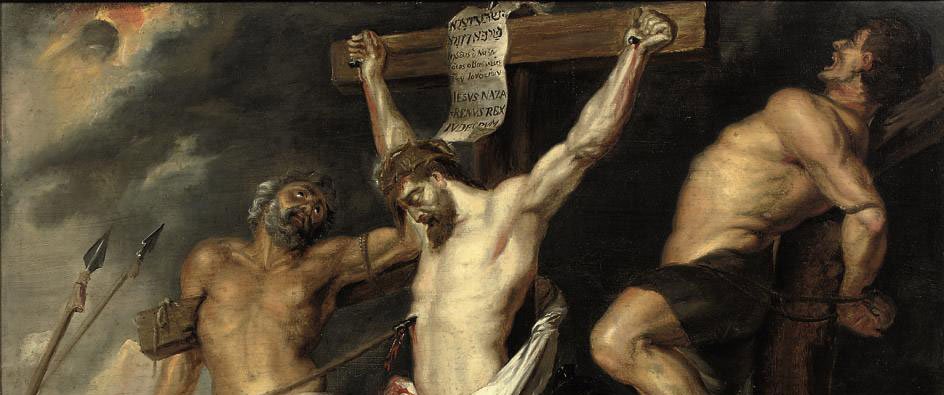

And now, if you did not know it before, you know why Jesus was called the “Lamb of God” (in, e.g., John 1:29 and throughout Revelation). He is also described as a “perfect sacrifice” (in Hebrews 9:14, for example).

But I am getting ahead of myself. God was made flesh in the form of a man (hence the phrase, “Son of Man”) whose arguably chief purposes on earth were to (1) serve as the perfect sacrifice and (2) teach humanity the meaning of the sacrifice and how to partake in it.

Whereas various animals might have had contained blood, the symbol of life, they were still dumb animals whose value was far less than that of any human. Jesus, on the other hand, was the Son of God, who was as perfect as God the Father was, and whose value was infinite. There could not be any more valuable sacrifice than if God came to earth in human form.

But matters are still not clarified satisfactorily. It makes little sense to most modern secular people to say that any sacrifice is literally or symbolically capable of turning aside God’s wrath, if the reason for God’s wrath is that his own purity and perfection were offended by his creation. (It is sometimes treated as rebellion.) A symbol might work a change in us, but it cannot make us perfect in God’s eyes. How could any sacrifice do so?

7. Salvation Through Faith

Answer: just as with Old Testament animal sacrifices, it is not the sacrifice itself, but instead what the sacrifice accomplishes in us.

To explain this, I will begin with a lot of phraseology you might have read in the Bible, and for skeptics, this might seem a little too religious and unpersuasive. I will tackle the critical question after this, promise.

Just as with Old Testament animal sacrifices, the meaning of the sacrifice of Jesus was symbolic. Its purpose was accomplished by the effect of that symbol on us. The brutal and painful slaughter of the Son of God would come to symbolize—literally, this is what the symbol of the cross means—and teach, and persuade us of several important truths:

- God loves us so much that he is willing to sacrifice his only begotten son, in an effort to perfect us (that is the meaning of John 3:16, perhaps the most famous New Testament verse). Being perfected, we will be saved from destruction at the “end of days.”

- If we take the time to investigate the accounts, we will conclude that Jesus really was the Son of God, because (a) he fulfilled many Old Testament Messiah prophesies, (b) he performed miracles in the name of God, and most importantly, (c) after dying on the cross, he rose again, as he predicted he would. Many Christians will tell you that the resurrection was and still is necessary to make faith in the divinity of Jesus possible.

- He declared that he was the son of God, the king of the the kingdom of God, prophesied by the Old Testament prophets. He began his ministry by declaring, “The kingdom of God is at hand” (Matthew 4:17). He made it very clear, through his own explicit words (“The Kingdom of God is within you,” Luke 17:21) and through the words of his disciples (Romans 14:17), that this means that you may be made a perfect subject of the kingdom of God by allowing the indwelling of the Holy Spirit.

In Jesus’ ministry, this was presented as news—good news—which is the meaning of gospel. Hence the cross, by symbolizing the sacrifice of Jesus, symbolized or pointed to the gospel that Jesus taught.

Very well. But I am aware that this is likely to be received as only so much religious palaver. And remember, it was such apparent palaver that gave an opening to the atheist who says, “And that will make all my bad actions all right, no problem? And that is why I have believe in Jesus? And that will stop me from burning in hell?”

I think the best way to make this explanation work is by further explaining, first, how it is that God can view sinful humans as perfect, and then to explain how a confrontation of the meaning of this sacrifice—indeed, our acceptance of the sacrifice—can have this result, i.e., the result of perfecting us.

God knows we are absolutely sinful and that it is impossible that this will change—at least, not without his help. God himself is perfect. But since we have souls, somewhat like God’s own great soul, and are created in his image, it is possible for the spirit of God—that is, the Holy Spirit—to as it were take up residence within us. Rather than being demon-possessed, God wants us to be God-possessed.

In practical terms, as best as I can make out, this means that if you pray faithfully to God and, in ways you cannot understand, he will work a change in your life. You gain a sense of what his will is, and you discover you want to do it. It is like a friendship or a mentorship, dominated by prayerful study and conversation. He gives you strength to do what is right. He makes you humbler. He makes you kinder. He changes your priorities in surprising ways. He puts you in touch with his other “sheep” so you can pray and do good works together.

But there is another layer to the explanation. Jesus was fully human when he came to earth, just like you, which is one of the most important reasons he is so relatable. If you believe that Jesus is the son of God, then it becomes possible for you to have a relationship with him. Why? Because Jesus is God incarnate (i.e., occupying a human form), and if the Holy Spirit is the spirit of God moving in us, it is also the spirit of Jesus moving in us.

You are enjoined to believe that Jesus died on the cross for your sins, and then you will be saved. The wording is important: you can believe that Jesus is the son of God without being saved. The demons in the Gospel accounts recognized Jesus to be the son of God, and of course they were not saved for their belief. But unlike demons, a Christian trusts in Jesus personally, i.e., he has a personal relationship with Jesus, and invites the spirit of Christ to enter into him and act through him, as it were becoming slaves to the will of God. (In letters, both Paul and James called themselves “slave of God.”) That is something the demons would not do; insofar as they are demons and not angels, they are essentially rebels. Jesus invites you to be more like angels than demons.

Through Jesus, God essentially offered humanity a deal. The deal is this: if you accept Jesus as your savior, welcoming him into your life, in the sense (very roughly) described above, then Jesus will do so. And then God can view you as perfect insofar as he, a perfect being, is acting through you. This is not to say that he wants you to be a puppet, and he wants to pull the strings. You must as it were freely give your will to him.

Very well. There are still many questions to answer here, but I will sidestep them for now. I am not trying to give a complete exposition of Christian theology but only of this particular set of doctrines about sacrifice, atonement, and the efficacy of faith. So let us return more explicitly to the question of sacrifice: if the purpose of sacrifice in general is to atone for your sins, and if this is a better sort of sacrifice that will go much farther, to make you perfect, then how did dying on the cross actually accomplish that? Why was Jesus sacrificed on the cross?

Of course, you and I did not sacrifice Jesus; that was 2,000 years ago. Rather, Jesus was executed by some Romans at the behest of the temple priests, all with the acquiescence of God. That sequence of events was treated by God as a sacrifice for the remission, or redemption, of sins. The repeated invocation of the language of “sacrifice,” the “lamb of God,” and “the blood of Christ” was merely symbolic. The symbol, it seems to me, stood for the Gospel, as I said. So how did it save us?

The short and glib answer I propose is: “Well, it sure made a lot of Christians, didn’t it? And that got them saved, didn’t it?”

I think something like that, ultimately, has to be the answer. Again, God did not change—not essentially—when Jesus was crucified. Jesus did come back in his glory, meaning roughly luminescent appearance, having visited heaven. But as the Word of God, he was there from eternity, according to John 1 and elsewhere, so that was not much of a change; it was just an aspect of him he had not previously revealed to anyone. But the Godhead was not changed by Jesus being sacrificed. We were changed.

Moreover, God sacrificing himself has no effect on us unless we accept what Paul calls God’s “free gift” of the forgiveness of sins through faith in Jesus Christ. The efficacy of the sacrifice has a deeply important condition. It is not unconditional. And that condition is faith. So why does Jesus demand we have faith in him? Is it, perhaps, that he only wants gullible fools in his heaven? That would be another silly atheistic canard. No, I have already explained it above: unless we do have faith in him, unless we personally trust him, we cannot possibly have a relationship with him, he cannot live in us, and through a sort of friendship or partnership with him, we cannot be made perfect.

I am not sure that this is a satisfactory explanation of why God wanted to sacrifice Jesus for our sins. I am aware that there is a whole body of theology, called theory of atonement, that I am not familiar with. So I suppose I could change my mind. In theologian Stephen D. Morrison’s typology, I am not even sure where the account I have given above fits, insofar as my account is coherent at all. (One of the commenters mentions Duns Scotus’ theory, which sounds vaguely similar to the one I have above.)

I do not expect this to persuade any nonbeliever, of course; why would it? I have not given anything like arguments for anything here. The hurdles that rationalists like myself must clear are more basic, like the existence of the soul, the afterlife, God, miracles, and so forth, and then accepting that Jesus is the son of God. I myself am not yet persuaded on all of these points, although recently I made a case the existence of the soul. But at any rate, there you have an explanation of why our Christian friends and family seem so excited about a body of doctrine that seems puzzling to many outside the fold. Could I ever join them? Indeed, perhaps I could.

Reply to “An Explanation of Divine Sacrifice”